Monday, March 31, 1975

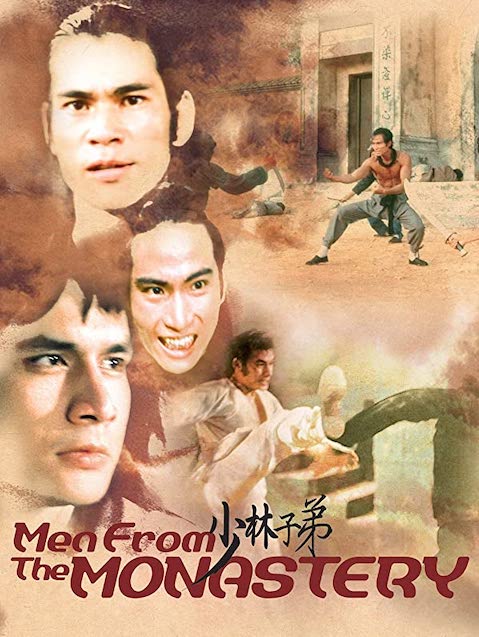

MEN FROM THE MONASTERY. Co-written by Ni Kuang. Music by Fu-ling Wang. Running time: Co-written and directed by Chang Cheh. Running time: Restricted entertainment in Mandarin with English and Chinese subtitles with the B.C. Classifier's warning: considerable violence throughout.

THERE SEEMS TO BE some confusion over which of the Shaw Theatre's current attractions came first. According to San Francisco City Magazine writer Michael Goodwin, "Heroes Two (is) the middle film of a trilogy comprising, in order, Men from the Monastery, Heroes Two and Shao Lin Martial Arts."

On the other hand, both the U.S. trade paper Variety, and the British Film Institute's authoritative Monthly Film Bulletin suggest that Heroes Two is the original and Men From the Monastery is the sequel.

What is clear is that film buffs on both sides of the Atlantic have discovered that there are "better" martial arts movies, and have begun to take them seriously. Attempts are being made to sort out the confusion of name changes, directors and performers as well as to analyze what MFB reviewer Verina Glaessner calls "one of the more interesting developments in recent Chinese film."

Receiving much attention is veteran Hong Kong director Chang Cheh. His recent amicable split with the multimillion-dollar Shaw Brothers organization is the "development" to which Glaessner refers. Although internationally distributed by Shaw, the Shao Lin trilogy was developed and produced for his own company, Chang's Film.

As to their order, I'm inclined to agree with Goodwin. Viewed together, Men from the Monastery looks like Chang's practice run for the technically more sophisticated, dramatically satisfying Heroes Two.

Both films are set in the same period and place: 17th century Canton. China's Ming dynasty has been toppled by Manchu invaders, but loyalist sentiment still burns in the Shao Lin monasteries.

Both films feature the same central characters. Young, cheeky and thoroughly charming is hero Fang Shih-yu (finely played by Chang discovery Fu Sheng). Thoughtful, serious and darkly brooding is hero Hung Hsi-kuan (played by All Southeast Asia Kung-fu Champion Chen Kuan-tai).

Where the films differ is in the basic dimensions of their story canvas and the degree to which each concentrates on battles and brawls to the exclusion of plot. Men from the Monastery, the more violent of the two, is less realistic.

Structurally, it is an anthology of four virtually independent episodes. The first introduces Fang Shih-yu, a Shao Lin brother who proves himself a martial arts master long before his formal education is completed, and who then returns to his home village to do battle with a hated Manchu leader.

The second episode belongs to Hu Hui-chien (Chi Kuan-Chun) a businessman's son who takes on a gang of Manchu masters to avenge the murder of his father. Despite his righteous anger, he's no match for the more skillful Manchus.

He is beaten up several times before Fang comes along to advise him to go to the Shao Lin school. Three years later he returns, a master, to have his revenge.

The third segment focuses on Hung Hsi-kuan, a patriot leader in hiding. "I kill Manchu dogs," he announces before dispatching a couple in the street. His dedication to his hobby causes the Shao Lin monastery to be razed.

In the final episode, the three heroes, with 10 companions, battle to the death with an army of Manchus. At the end, only one man is left alive to carry on . . .

If the public was satisfied with Men from the Monastery, Chang Cheh wasn't. His Heroes Two, a film that begins with the destruction of the Shao Lin establishment, narrows its scope to intensify its impact.

In this version, Fang (conveniently resurrected) and Hung do not know one another. Inadvertently, the flip Fang is responsible for the capture of the more serious-minded Hung. Discovering his error, he makes himself responsible for the No. 1 patriot's rescue.

Chang learned several lessons from his first film. This time, for example, he offers filmgoers a pair of villains, General Kang Che and the evil Teh (played by Chu Mu and Wang Ching), who are not only as proficient as his heroes, but whose characters are as well developed. Dramatic as well as physical conflict enters the picture.

At the same time, Chang shows how well he has polished his cinematic technique. There are fewer jarring zooms, fewer close-ups of open wounds, and less artificial blood is shed. Here, his innovative use of monochromatic battle scenes and slow-motion death blows is disciplined to the point where it actually adds to the impact of the final confrontation.

In Heroes Two, Chang has made a film for the Kung-Fu cognoscenti without sacrificing general audience appeal. His films are the first martial arts movies I’ve run across that actually seem designed for people who don’t like martial arts movies.

An action director with an epic sense, Chang Cheh has managed to develop a pair of first-rate characters and evolved a story style that suits them well. The third part of the trilogy is a film worth waiting for.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1975. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: As it turns out, the Shao Lin Temple (currently known as the Shaolin Monastery) has been razed (and rebuilt) many times during its 1,500-year history. Men from the Monastery was inspired by the destruction that occurred in 1644, and the stories of the fugitive monks who spread the practice of martial arts in its aftermath. Just as Alamo remembrance has achieved mythic proportions in American popular culture, so Shao Lin has its place in what it means to be Chinese. In the mid-1970s, that meaning was complicated by the fact that the story was shaped by moviemakers who reflected the different perspectives of Hong Kong (a British Crown colony), Taiwan (officially recognized as “China” by the U.S.) and Mainland China (not officially recognized by the U.S. until 1979). And then there was Kung Fu, ABC-TV’s three-season Western/martial arts mashup (1972-75), that starred David Carradine as a fugitive mixed-race monk on the American frontier of the 1870s.

A full semester of social studies classes could be based on the issues in play. Among other things, there is the matter of religion in modern Chinese politics. Much is made in the West of Beijing’s “persecution” of its Uyghur minority (and before that of the Falun Gong sect). Less attention is given to the historic tension between Chinese governance and insurrectionist organizations based on religious beliefs. Also worth remembering is that 19th-century Christian missionary activity in China occurred at a time when the European, American and Japanese empires all held mercantile “concessions” that constituted an occupation of the Asian nation. There’s a lot of pent-up anger in 21st century China’s dismissive attitude towards U.S. human-rights rhetoric. But that’s hardly surprising, given the anger that simmers beneath the surface of such films as Chang Cheh’s Men from the Monastery.

In the above review, I expressed my opinion that Shao Lin Martial Arts, “the third part of the trilogy, is a film worth waiting for.” Although I’m sure it found its way to Vancouver, I managed to miss seeing it.

Double feature: Yes, I reviewed director Chang Cheh's Heroes Two. Twice.