Thursday, April 8, 1971.

ACROSS THE CANADIAN PRAIRIES and on the rolling Ukrainian steppe, Lent is drawing to a close. For more than half a million Canadians, followers of Eastern rite churches, next week is Holy Week.

In many of the Ukrainian homes, women are already about the business of preparing the traditional Easter celebration, and some may be passing on to their daughters the 1,000-year-old legend of the pysanky.

One morning, in the Roman province of Judea, a young woman was making her way home from market. It was springtime, shortly after Passover, and she carried with her a basketful of freshly laid eggs and, because the way was long and dusty, a bag of water.

Coming to a crossroads, she met a stranger. He sat on a rock by the path, and looked weather-worn, tired and thirsty.

She offered him water. He rose to accept it, and she was startled to see that his hands were split open with fresh wounds. She said nothing, however, and without a word the stranger went off down the road.

The young woman continued home. When she arrived there and opened her basket, she found it filled with pysanky, the exquisitely designed and decorated eggs that have become the Ukraine's most familiar form of folk art.

The creation of pysanky (from pysaty — "to write") is uniquely Ukrainian. Though many nations traditionally colour eggs for Easter, none has ever approached the task with quite the same mixture of style, skill and artistic intensity as the Ukrainians.

Eggs, coated in beeswax except for a carefully etched pattern, are dipped in colouring. Coating, etching and dipping are repeated as often as is necessary to produce a desired effect or a proper combination of colours.

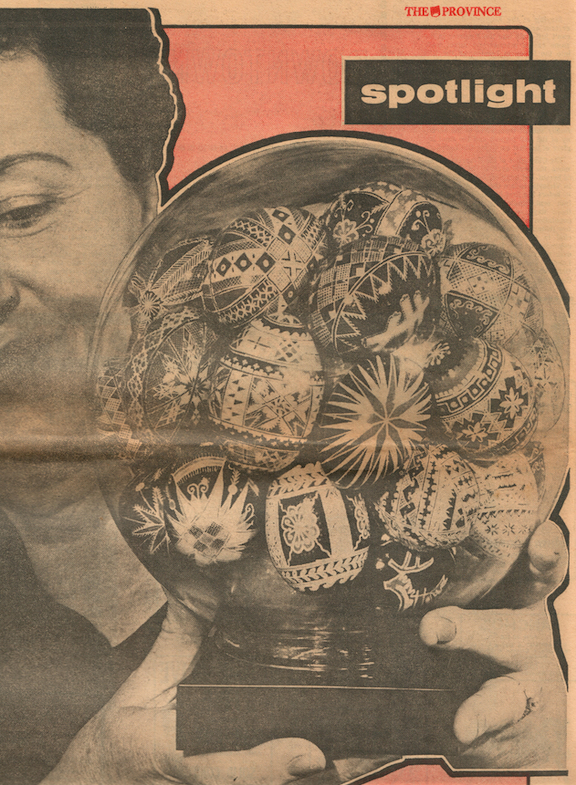

The results are stunning. Each pysanky emerges as its own complex world of colour and design. Some appear to be multicoloured exercises in geometry, some burst upon the eye kaleidoscopically, some vary a theme like the cross or a star.

Some are patterned with livestock, wheat sheaves or blooming flowers. Some may be miniature canvases for landscapes or still-life portraits. The variety is endless because, it is said, no two pysanky are ever the same.

The pysanky form an important part of the devout Ukrainian's Easter ritual. Along with the paska, the specially decorated Easter loaf, pysanky are taken along to the parish church to receive the priest's blessing.

At the beginning of the annual Easter feast, the blessed foods are laid out on the table, and the oldest member of the household cuts one of the sanctified eggs into as many segments as there are persons at the breakfast.

Each is offered his portion with the greeting Xrystos voskres! (Christ has risen!). Each receives it with the reply Voistyno voskres! (He is risen indeed!).

The remaining pysanky are exchanged among friends and relatives, or added to the family's own collection. The gem-like eggs are treated with considerable respect, not only for their beauty and the amount of creative work they represent, but for the blessings they bear.

Once consecrated, they become true Easter eggs and, because they enjoy a direct relationship with those first legendary pysanky, they're believed to be able to insure the flow of God's graces into the household.

Historically, pysanky predate the Christianization of the Eastern Slavs. Although written records reach back no further than the 13th century, many of their basic motifs have been traced back to the neolithic age.

For millennia, Ukrainians have been an agricultural people, living by the cycle of the seasons and the fertility of their land. In the centuries before Christ, they learned to be loyal to the creative powers of the sun, recognizing in the egg a reflection of the solar power.

An egg contained the germ of life which, when hatched, could be a cock, the sun's own morning herald. By the same reckoning, eggs were an ideal offering to the dead, who were expected to use the packaged regenerative powers to insure the continued cycle of plant and animal life.

Ritually, pysanky harnessed the power of the sun and spirit worlds, life and death. Their special time was the spring, when the sun returned to melt the winter's snow and life of all kinds returned to the steppe.

Then, in 988, Christian missionaries arrived with a new message of life and death. An extra layer of meaning was added to the ancient egg symbols. Although the Son replaced the sun, pysanky were given new status to serve Him.

When Ukrainians began arriving in Canada, they brought Eastern rite Christianity and their pysanky craft with them. Day-to-day life on the Prairies was much as it had been on the steppe, and the tradition continued to be handed down from one generation to the next.

Although egg-decorating was a traditional art, it was not tradition-bound. The pysancharky (egg decorators) looked around their new land for ways to improve their craft.

Dyes boiled from crepe paper, indelible pencils, commercial food colouring and textile dyes were all found to be just as effective as the laboriously compounded natural colourings. Even something as simple as the metal tab from the feed-and-grain-store calendar could be pressed into service. These were used to tip the etching stylus.

Today, pysanky have lost much of their specific religious significance. Instead, they've become a colourful and demanding folk-art form.

They can be seen throughout the year at church sales, folk festivals and competitions where artists, who are no longer rural, hone their skills to a fine professional edge.

In doing so, the modern pysancharky have evolved a new symbolic status for their beautiful, delicate decorations. More than "Easter," their eggs say "Ukrainian,” and say it in a way that's both vivid and unique.

The above is a restored version of a Province feature article by Michael Walsh originally published in 1971. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Before becoming The Province’s full-time film critic, I spent three years as an entertainment department feature writer, producing cover stories for its weekly Spotlight magazine supplement. In April 1971, photographer Gordon Croucher and I visited Olive Kindrachuk, an executive member of Vancouver’s Ukrainian Women's Association, who conducted egg-etching classes during the Lenten season at the Holy Trinity Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church. The result was a four-page spread that included the above article on the place of pysanky in Ukrainian culture, and a photo-illustrated guide showing her making one for us. It also included the information that: “During the month of April, a display of her eggs is on view at the Burnaby Art Gallery. Tomorrow (Good Friday), Mrs. Kindrachuk will demonstrate her art in person, both at the Burnaby Art Gallery and on Channel 8’s Jean Cannem Show,” the daily morning show on BCTV.