Wednesday, October 9, 1974

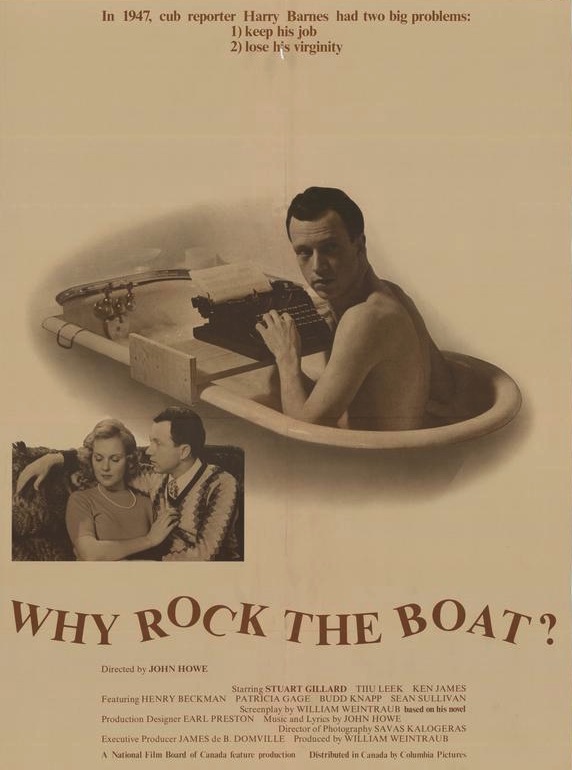

WHY ROCK THE BOAT? Written and produced by William Weintraub based on his novel. Music composed and film directed by John Howe. Running time: 112 minutes. Classifier's warning: occasional coarse and suggestive language. Mature entertainment.NEARLY TWO DECADES ago, in the same year that a prairie visionary named John Diefenbaker first came to power, University of Toronto political economist James Eayrs was asked by an American foundation to analyse the differences between the U.S. and Canada. Eayrs did so in a brief, brilliant essay called Northern Approaches.

In it, he quoted anthropologist Margaret Mead: "If 'cope' is a typically British verb. 'fix' is typically American." The corresponding Canadian word, Eayrs suggested, is "adapt."

His comment provides us with the key to the controversy that's likely to divide filmgoers who see the National Film Board's feature Why Rock the Boat?, a film you'll either like or hate.

Significantly, it has been subtitled "a romantic comedy." A project developed by writer-producer William Weintraub and director John Howe, it is an homage to the populist romances of depression-era America, a film that Canadianizes Frank Capra.

The result is a gentle, unhurried movie that not only captures the sense of its period, but fulfills the NFB mandate to "interpret Canada to Canadians," doing so with discomfiting accuracy. Although reaction to the film has been mixed, it worked for me.

Part of my enjoyment came from the fact that the film is set in a newspaper milieu. Weintraub's original 1961 novel mercilessly satirizes life in Montreal's newsprint jungle, circa 1947. Its hero, Harry Barnes, is a junior reporter on The Daily Witness, affectionately known to its staff as "the worst newspaper in the whole Dominion of Canada."

Well, we've all been there. This is an itinerant business and there's hardly a newsman in the country who hasn't, at one time or another, worked for a sheet that fitted that description to a T.

Weintraub captured it in his book and Howe recreates it on screen. But, as their deliberate subtitle points out, that's not what their film version is all about.

The movie is a tale of maturation the Canadian way, a Winter of 47 designed to freeze away the lingering bad taste of that Summer of 42 (1971).

This is a picture that turns the traditional Capra approach upside down. In doing so, it reveals much about the differences in our own time and place, differences that give Why Rock the Boat? its distinctive, refreshingly Canadian flavour.

Sicilian-born Frank Capra was one of the sound era's first message-mongering moviemakers. His best known films — among them, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) and Meet John Doe (1941) — all carried with them an intentional dose of social commentary, along with reporters as principal characters.

During the Great Depression, however, people were not going to the movies for lectures. They wanted to be entertained and, for the sake of sales, the love interest was kept to the fore. Filmmakers had to provide a hero and heroine who would live happily ever after.

Today, for the most part, the opposite is often true. There are producers who think that the promise of social significance is necessary to draw audiences into a love story.

Last year [1973], The Way We Were offered the lure of nostalgia and the clash of political ideologies. Now, Why Rock the Boat? comes along with more nostalgia and Weintraub's delightful send-up of the daily press.

At heart, though, it is a comic love story revolving around themes of sexual and social maturation. Alberta-born Stuart Gillard, unmemorable in either The Rowdyman (1972) or The Neptune Factor (1973), gives Harry Barnes the kind of tentative awkwardness and likable self-righteousness that distinguished James Stewart in his Capra film roles.

His Harry wants to succeed but, in that distinctively Canadian way, he is even more concerned with obeying the rules. "If you want to get along around here," advises veteran reporter Fred O'Neill (Budd Knapp), "don't bang your head against the wall, don't try to change the world and don't rock the boat."

Harry accepts that. No radical, he is making the princely sum of $18 a week and sees no reason to jeopardize his future. Then love walks into his life in the appealing form of Montreal Telegram reporter Julia Martin (Tiiu Leek).

Julia is the sort of female who used to turn up in newspaper city rooms before the age of women's lib. Beautiful but distant, she probably got her job because of her good looks. Once working, though, she resents the fact that her talent is suspect precisely because she is so attractive.

A former fashion model, Leek perfectly reflects the anguish of a woman so determined to excel that she never realizes that she is out of her depth. Harry, of course, falls hopelessly in love with her and spends the rest of the movie attempting to sort out his life and win this impossible dream.

Along the way, he serves his journalistic apprenticeship. Like Duddy Kravitz, another Montreal youth from roughly the same period, Harry is surrounded by vivid role models.

Weintraub's screenplay contrasts the principles of people like O'Neill ("why rock the boat?") with those of kindly city editor Herb Scannell (Sean Sullivan), who would like to make his newspaper "the New York Times of Canada," and earthy photographer Ronnie Waldron (Ken James), who keeps a $5 bill clipped to his driver's licence.

One evening, Harry watches Ronnie pay off a policeman to avoid a parking ticket. "But," he protests, "the ticket would only have cost you $2."

"It's a matter of principle," says Ronnie.

Overshadowing them all are the principles of managing editor Philip L. Butcher (Henry Beckman), the penny-pinching tyrant who rules his newsroom like a feudal fief. The embodiment of every management evil any of us have ever known, Butcher is the pawn of the privileged and the agent of the advertiser. He has made The Daily Witness "the champion of the overdog."

Still, when the time comes to make his choice, Harry leans toward the cliche radicalism of his beloved Julia. "I'm not really a radical, he confides to Waldon in the confessional-like intimacy of the photographer's darkroom. "Actually, I believe in everything she hates. I believe in patriotism. I believe in a wife and kids in the suburbs. I believe in kind-hearted capitalism."

In adapting the screenplay from his original novel, Weintraub emphasizes Harry's romantic problems. In doing so, he creates some problems for the contemporary audience, most obviously the matter of language.

Although his characters talk pretty much the way people talked in 1947, that's not the way we remember them talking in the pictures of the period. There is a quaintness in the euphemisms used by tough guys like Clark Gable and Humphry Bogart in their movies, a quaintness that could have added period atmosphere to Why Rock the Boat?

Innuendo, after all, can be fun and Weintraub knows it. One of the film's most successful scenes is Harry's seduction by the love-hungry wife of his city editor, played by Pat Gage, who honed her talents as a vixen in director Larry Kent's last film, Keep It in the Family (1973). The scene is a gem because, throughout, the subject under discussion is popcorn. The result for Harry is the loss of his hated virginity.

To beef up Julia's role, Weintraub adds an entire subplot to his original story, something that impedes the film's overall pace. Now his characters are involved in the labour union movement, a change that provides the piece with its major strength and creates its major weakness.

On one hand, Howe is able to stage a typically Capra climax, a rousing crowd scene in a public place, in this case The Daily Witness newsroom where Barnes, fortified by some expensive Canadian rye whiskey, confronts the arch fiend Butcher. On the other hand, the story alterations change some of the essential relationships and effectiveness of some of the characters.

In the book, the idealistic city editor Scannell emerged as the ultimate savior of The Daily Witness and the integrity of Canadian journalism. In the film, the reporters form a union and he is left to exit in tatters, a failed dreamer and a cuckold to boot.

Last week, in an interview, Weintraub suggested that the changes were purely for the purpose of emphasizing the tale's romantic elements. After seeing the film, though, I suspect that there was more to it than that.

Between them, Weintraub and Howe have delivered audiences a long, slow satirical curveball. Working with a superb cast, they have delivered on the comedy and romance. Working with considerable subtlety, they also deliver an incisive analysis of contemporary manners and morals.

According to Canada's Film Commissioner Sidney Newman, the National Film Board costs each taxpayer 78 cents a year. I'd say it's change well spent.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1974. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

AFTERWORD: Arguably, producing fictional feature films was not something the federally-funded National Film Board was mandated to do. Founded to "interpret Canada to Canadians and other nations," it might have stuck to it's award-winning documentary ways if the private sector had risen to the challenge of creating a domestic film industry. In the 1960s, in the absence of such an industry, the Board expanded its role and produced Drylanders, the story of the Greer family and their years of homesteading in Saskatchewan. By 1974, the year that Why Rock the Boat? reached theatre screens, the NFB had become the nation's graduate film school. Today, with more than 200 fictional features to its credit, the Board can take pride in having been a major contributor to Canadian cinema.