Tuesday, April 21, 1970

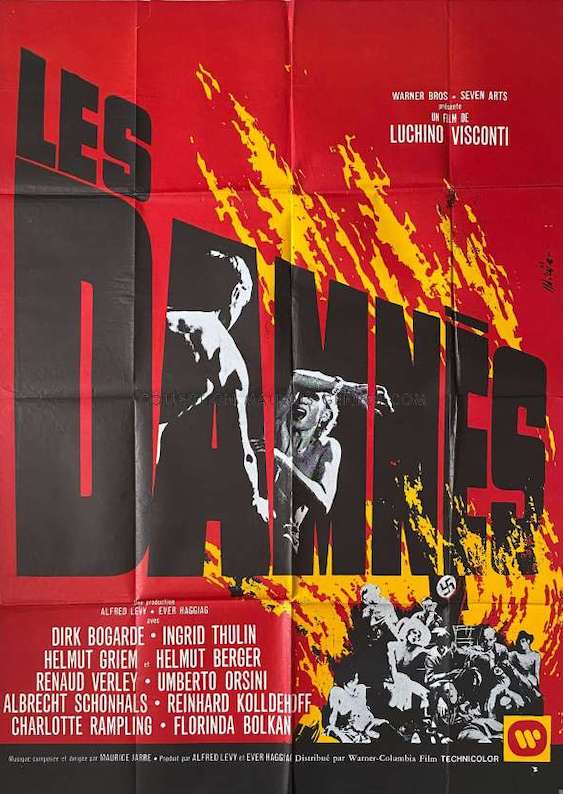

THE DAMNED. Co-written by Nicola Badalucco and Enrico Medioli. Music by Maurice Jarre. Co-written and directed by Luchino Visconti. Running time: 156 minutes.

BURT LANCASTER SPOKE A fitting preface to Luchino Visconti's latest film nine years ago [1961]. Lancaster was playing Ernst Janning, a Nazi jurist facing a post-war Judgment at Nuremberg.

"I wish to testify about the Feldenstein case,” he told the Allied tribunal, "because it was the most significant trial of the period . . . but, in order to understand it, one must understand the period in which it happened."

Visconti's new movie, The Damned, might well have been called The von Essenbeck Case. In it, the Italian director tries to explain the rise of Hitler's Reich by relating his own parable of the cannon-makers.

"There was a fever over the land,” Lancaster’s Janning told earlier audiences. “We had a democracy, yes. But it was torn by elements within. Above all there was fear . . .”

The Damned opens in the von Essenbeck mansion. On the same winter evening that Hitlerite arsonists chose to burn down Germany’s Reichstag building, the Krupp-like family of aristocrat-industrialists is gathered in honour of its patriarch's birthday.

All of the complex forces shaping the new Germany are represented around Baron Joachim von Essenbeck's (Albrecht Schoenhals) table. Friedrich Bruckmann (Dirk Bogarde), an ambitious, social-climbing technocrat, has come courting the amorally calculating Sophie (Ingrid Thulin), widow of the baron's eldest son.

Her adult son Martin (Helmut Berger) is a third-generation von Essenbeck, morally degenerate, emotionally crippled and direct heir to the corporate presidency.

Konstantin (Reinhard Kolldenhoff), the baron’s second son, is an officer in the brownshirted S.A., the Nazi street militia. His son, Güenther (Renaud Verley), is a naive, non-involved, cello-playing intellectual.

The baron's daughter Elizabeth (Charlotte Rampling) is married to the corporation's liberal-minded vice-president, Herbert Thallman (Umberto Orsini). And finally, hovering quietly in the background, is shadowy cousin Aschenbach (Helmut Griem). Smiling and sinister, he is a blackshirted S.S. officer.

Before the night is out the old baron, symbol of pre-Hitler Germany, is dead. Before his corpse is cold his family, like the nation, is locked in a fierce power struggle, scrambling for control of a vast munitions empire.

“Personal morals are dead,” the cunning Aschenbach tells Friedrich. "'Anything is permissible' — these are Hitler's words."

Hitler's words, perhaps. Visconti's, certainly. Unfortunately, such words hardly seem natural to the film's characters. The weight of the director's metaphor sits heavily on his international cast's back, allowing little room to develop any genuinely human personalities.

They all have been drawn as symbolic figures, and straitjacket the performers into Visconti’s ponderous allegory. Nor is their cause helped by the film's painfully poor dubbing.

The Damned is subtitled "Gotterdammerung.” The allusion to Wagnerian opera is appropriate. Like the German composer, Visconti undertook a project of epic proportions. Like Wagner, he has engineered a teutonic tour de force, hard-edged, heavy, mirthless and mechanical.

There is no denying Visconti's artistic achievements. The images are stunning and completely consistent with his epic theme.

The baron's funeral procession, set off against the bleak, grey steelworks; an S.A. outing, aflame with the ruddy passions of political conviction, arrested adolescence and Munich beer; S.S. headquarters, bleached and claustrophobic with files — each is a striking vision, etched with a sure feeling for colour and composition.

The director's storytelling ability is less impressive. His von Essenbecks are little more than George Grosz cartoons, sharply sketched caricatures rather than characters.

Each one's fate has been historically sealed before the drama ever begjns. The audience is left with an enactment of a tragic ritual. Cousin Aschenbach uber alles.

A man who personally combines philosophic Marxism with a passion for grand opera, Luchino Visconti has little use for Nazism. He could, however, have used a little more restraint in his indictment of it.

Perhaps the Nazi leaders were drug-addicted, child-molesting, incestuous, matricidal transvestites. But as Spencer Tracy, in his role as the presiding judge in Judgment at Nuremberg, pointed out: “If all the leaders of the Third Reich had been sadistic monsters and maniacs, then these events would have no more moral significance than an earthquake, or any other natural catastrophe"

Nazism mattered. Less than forty years ago [1933], it swept Germany like a fever and drew the world into a war.

"Those days," Visconti has said, "must not come again."

Unfortunately, The Damned, his joyless horror-myth of Nazi decadence, attempts to be artistic rather than analytic. Conceived coldly and without compassion, his film is an exercise in formal structure that contributes little to either popular understanding or entertainment.

The above is a restored version of a Vancouver Express review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1970. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Italians take a special interest in fascism. They’re entitled, because after all, they invented it. OK, that’s not entirely true. The online encyclopedia Britannica assures us that the ideas that we call fascist today have their roots the 19th century. A theoretical backlash to the secular liberalism and social radicalism that accompanied the progressive revolutions of the day, such ideas were abroad in Britain, France and Austria, as well as Italy and Germany.

Italy is special because it was home to the first social organizations to use the word — fascio, a bundle of sticks that together are stronger than a single stick, came to be the symbol of the movement that was fascism — and the first country to have a fascist political party come to power. Benito Mussolini took control in 1922, a full decade before Adolf Hitler was appointed the German Chancellor. Italy’s film artists had considerable lived experience to draw upon in the post-war years.

At a time when Hollywood was being rocked by a new generation — the Easy Riders, Raging Bulls film historian Peter Biskind focused on in his 1998 survey of 1970s cinema — Luchino Visconti’s The Damned insisted that fascism remained unfinished business. He was not alone. In the next few years, almost every major Italian director weighed in on the subject in one way or another. Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1970 drama The Conformist was a movie that examined the psychological costs of going along to get along circa 1938.

In stark contrast to Visconti’s portrait of Germany’s von Essenbecks, Vittorio De Sica’s The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1970) told the story of a wealthy Italian Jewish family’s struggles during the war years. Two years later, Federico Fellini charmed audiences with his Oscar-winning Amarcord (1973), a comedy that drew upon his own teenaged memories of life in coastal Rimini. And then things got rough.

Linking fascism with sexual perversion made Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter (1974) both controversial and a boxoffice hit. Made in English, it starred Charlotte Rampling as a concentration-camp survivor who resumes her sado-masochistic relationship with former Nazi guard Dirk Bogarde. (Along with 1975’s Ilsa - She Wolf of the SS, it’s been called Nazispoitation.) Then came Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), in which the abuse of young prisoners in wartime Italy by wealthy fascists is shockingly expicit. Finally, Caligula director Tinto Brass offered Salon Kitty (1976), based on the true story of a luxury Nazi brothel where the sex workers are trained to spy upon their high-ranking clients.

Lina Wertmüller became the first woman nominated for a best director Acadamy Award for her 1975 feature Seven Beauties. Also nominated was the picture’s star, Giancarlo Giannini, who played a small-time Sicilian gangster who’ll do anything to survive the war. Bertolucci was back in 1976 with 1900. An historical epic that flashed back from the end of the Second World War to tell the story of Italy in the 20th century, it featured a cast studded with international stars. Nor can we forget Ettore Scola’s A Special Day. It recalls the historic moment in 1938 when the Fascist superstars Hitler and Mussolini met in Rome. An Italo-Canadian co-production, it starred John Vernon along with Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni.