Friday, February 9, 1973.

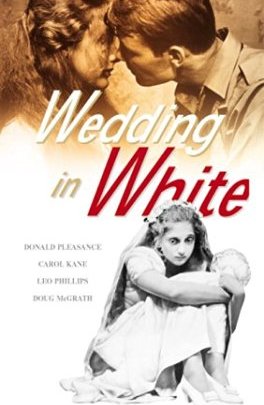

WEDDING IN WHITE. Music by Milan Kymlika. Written and directed by Bill Fruet. Running time: 103 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: frequent coarse language.

KHAKI WAS THE COLOUR of the 1940s. Together with olive drab, ochre and dun, it's the colour that spreads across the mind’s eye when the war years are recalled.

It is the colour that continually underscores the mood in writer-director Bill Fruet’s honest and overwhelmingly evocative film, Wedding in White.

Honoured as the best film of 1972 at the recent Canadian Film Awards, the original story was written by Fruet from his own vivid recollections of the period. Although it was first produced as a stage play in Toronto, it was always meant to be a movie.

It has reached the screen splendidly, a fully realized vision and the best English-language Canadian film yet to play in Vancouver. Fruet, who scripted Don Shebib’s features Goin’ Down the Road (1970) and Rip-Off (1971), makes a solid directorial debut.

Wedding in White is a film that calls up the shades of an era only dimly remembered, a sepia-toned time of ill-fitting uniforms, bravado and borrowed glory. By bringing it into sharp focus, the movie manages to strip away the layers of protective gloss and reveal it for what it was: a time of dulled colours reflecting the dullest dreams of unhappy people imprisoned in an unhappy time.

It is a story set on the home front, one centred on a 16-year-old girl whose romantic fantasies are shattered by sexual reality. Put in just that way, Wedding in White could be mistaken for a companion piece to Robert Mulligan’s Summer of ’42.

It’s not. Whereas Mulligan’s 1971 Hollywood film was an exercise in contrived nostalgia, a formula film designed to excite the tear ducts of adolescent girls, Wedding in White is hard-edged adult entertainment. In style and content it shares much with the gut reality of Peter Bogdanovich’s black-and-white The Last Picture Show (1971).

It’s a tale told in khaki, the mean, confining colour of uniforms and uniform thinking, played out in the small Ontario town where the Dougall family has sunk its lowland Scottish roots. Big Jim (Donald Pleasence), its patriarch, remembers the Great War and serves in Canada’s Veteran Guard, keeping order in the P.O.W. camp just outside of town.

His son, Jimmie (Paul Bradley) is a loutish loudmouth serving with the regulars. The new war has brought a kind of purpose into the men’s lives, although the uniforms have clearly trapped them into living out a myth of larger-than-life manhood.

The women of the family — Mary (Doris Petrie, who won the CF Award for best actress) is a fussy little mother; Jeannie (Carol Kane), her ethereal, distant daughter — are trapped in a different world, one bounded by the faded yellow walls of their kitchen.

One weekend, Jimmie arrives home on leave with his barracks buddy Billy (Doug McGrath) in tow. Jeannie is smitten with the newcomer, but he is more interested in her worldly, teasing girlfriend Dolly (Bonnie Carol Chase).

Frustrated by the flirt, Billy ends up raping his friend’s shy sister in the darkened living room. Later, when Jeannie discovers she is pregnant — “I think I’m in trouble,” she tells her mother with downcast eyes — her entire world caves in upon her.

At first her father, thunderstruck by the disgrace to his household, seems angry enough to kill her. Restrained by his old war buddy Sandy (Leo Phillips), he is then determined to cast her out.

Finally, he settles on marrying her off — make an honest woman of her — when aging widower Sandy offers himself as the bridegroom.

Fruet’s film is a deep and probing study in character, finely directed and well acted. Pleasence, a sensitive English actor whose mad eyes have typecast him as a villain in his recent American movies, is flawless as the tyrannical Jim, an aging bigot who sees his own narrow-mindedness as simplicity and straight-forwardness.

Withdrawn and reacting continuously to the performers around her is Carol Kane, a New York stage actress who brings a fragile, tragic feeling to the role of Jeannie. She sees in her mother a vision of what she will become, and in her brother what her father must have been.

With the exception of Pleasence and Kane, all of the personnel, both before and behind the camera, are Canadian.

Cinematographer Richard Leiterman, an artist used to confined spaces — director Allan King's documentary features Warrendale (1967) and A Married Couple (1969) were both shot inside private homes — handles the location work as if it were a set built to his own specifications.

Art director Karen Bromely, another CF Award winner, has recreated the period right down to the Star Weekly clippings on the bedroom walls. Ultimate credit, though, must go to Fruet, who conceived the project and carried it through to the screen.

Wedding in White, in its strength, style and sensitivity, sets a new standard in excellence for Canadian films. A story of personal tragedy, it is a cinematic triumph.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1973. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Paul Bradley “lived pretty close to the street,” Doug McGrath said in a 2011 interview. The two young actors made their feature film debuts in director Don Shebib’s Goin’ Down the Road, and shared the 1970 best actor Canadian Film Award for their performances. McGrath talked about his late friend during the making of Down the Road Again, a sequel that has been described as “a requiem” for Bradley (who died in 2003). “He certainly drank a lot,” McGrath told the Globe and Mail’s Guy Dixon. “Maybe there was a great sense of disappointment in him that it didn’t happen, didn’t go further, especially with the great talent he had.” They worked together on Bill Fruet’s Wedding in White, and then again on 1973’s The Hard Part Begins, directed by Paul Lynch.

What all of those films had in common was their focus on a kind of dead-end reality. They also represented an unintended consequence of a positive government initiative called the Canadian Film Devolopment Corporation (CFDC). Founded in 1967 to "to foster and promote the development of a feature film industry in Canada,” the federal agency was born in the can-do spirit of Expo 67. The first production monies were allocated in 1968 and, by 1973, CFDC executive secretary Michael Spencer was beginning to have serious misgivings about Canadians' self-image.

"What we don't need is another movie about the Great Canadian Loser,” Spencer complained to me in a kitchen-table conversation in Vancouver. Given the opportunity to make their own movies, Canadian artists had gone for the grit. Shebib’s Goin’ Down the Road, the classic tale of two Atlantic Canadians who fail to make their fortunes in Toronto, was soon followed by Wedding in White and Newfoundland’s The Rowdyman (1972), by British Columbia’s The Rainbow Boys, Saskatchewan’s Paperback Hero (1973) and The Hard Part Begins (all 1973). Spencer was depressed because, he believed, films about failures were films destined to fail. That the CFDC failed to support the promotion and distribution of such Canadian movies after they were produced made Spencer’s belief a self-fulfilling prophecy.