Tuesday, March 21, 1970

WHEN LEW YOUNG opened up his Surf Theatre 18 months ago [September 1968], nudie films were the furthest thing from his mind. Port Coquitlam, with a population of 15,000, seemed like the right place to open a family-format movie house.

The old Column Theatre on Shaughnessy Street was even equipped with a glass-walled crying room, for mothers with noisy infants. Young, a licensed projectionist, decided to take the risk.

Leasing the run-down auditorium, he gave it a new name and set about refurbishing the place. A year passed.

The family film policy proved to be a qualified success. Although it was no moneymaker, it at least allowed the house to break even.

If the Surf was to grow, however, it would have to do better than that. So, after much thought and some legal advice, independent operator Young decided to book the only product that the major chains wouldn't touch — the exploiters.

An American distributor specializing in nudie potboilers was happy to have a B.C. exhibitor, and has supplied the Surf with a steady stream of "first run" attractions for the Vancouver market. All his pictures must, of course, be pre-screened and approved by the B.C. provincial film censor, Ray MacDonald.

On January 12, the Surf introduced its "adults only" policy. On its final evening as a family theatre the 449-seat house took in $32 at the box office. The next night, Young says, the take was over $800.

All is not bosoms and bottoms, though. Young's bright, clean little theatre would probably not be recognized as a nudie house by the regular patrons of the more than 400 sleazy picture parlors on the U.S. sex-film circuit.

Young is trying to do better by his audience in another way, as well. Beginning with his current program, he plans to lend weight to his bookings with a "quality" second feature, a major studio production that hasn't been seen in a few years.

Perhaps, when the current interest in epidermal epics passes, the crowd will keep coming back for the better films. The Surf Theatre still has its crying room.

* * *

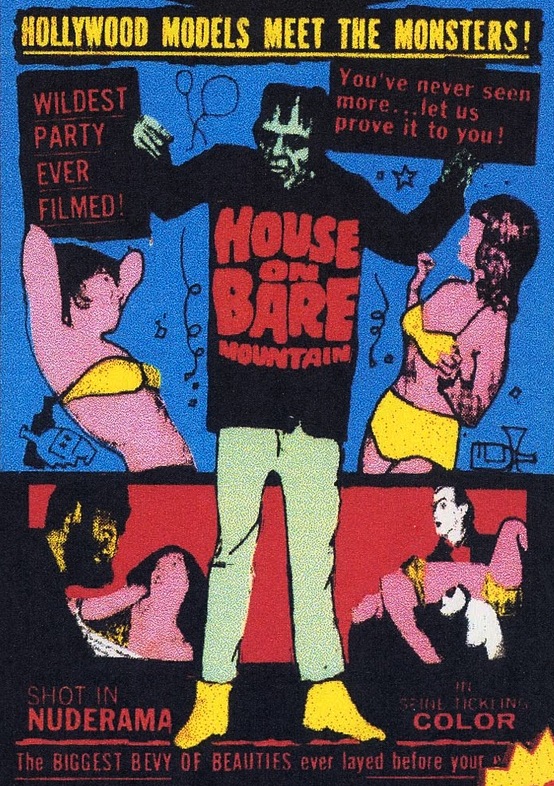

Currently [March, 1970] on view at the Surf Theatre:THE HOUSE ON BARE MOUNTAIN. Written by Denver Scott. Music by Pierre Marte. Directed by R. Lee Frost. Running time: 62 minutes. Restricted entertainment.

ASKED TO DESCRIBE HIS 1969 New York stage revue, Oh! Calcutta!, British critic Kenneth Tynan called the show "an erotic entertainment for sophisticated adults."

Asked to describe his Olympic International movie, The House on Bare Mountain, producer Robert Cresse said: "It's a silly little comedy — totally innocuous."

What both shows have in common is nudity. On stage, with a top ticket price of $25, the nudity is total, male and female. The theme of Oh! Calcutta! is the sex urge and each sketch involves a simulated connection.

On screen, for a $2 admission, it's animated Playboy. In the style of that magazine's photo features, a platoon of young beauties go about their everyday activities in the revealed/concealed manner of its famous gatefold girls.

And Cresse is at pains to point out that "a sexual act never takes place in the film. You couldn't conceivably find anything obscene in it."

Within the movie business, his film is called "a nudie." Its genre was born late in 1959, following a New York Appeals Court decision that nudity, in and of itself, could not be obscene.

The ruling opened the door for a rush of quickly-produced, low-budget movies. Naked and near-naked girls were featured in a host of non-obscene activities, including sun bathing, shower bathing and go-go dancing.

For the movies themselves, comedy was the safest pose to strike. Thus, a slight and usually sophomoric plot would be added to sketch in some background and tie the loosely conceived scenes together.

A classic of its kind, The House on Bare Mountain introduces Granny Good (Bob Cresse), the kindly dean of her own School for Good Girls. As played by producer Cresse, Granny affects the style of Jonathan Winters's lovable tippler Maude Frickert.

Local police, suspecting that Granny's hilltop college is really fronting for a bootlegging operation, send in a secret agent named Prudence (Laura Eden). While sniffing out the illegal still, the new girl will, of course, participate in all of the school's healthful, hygienic activities.

Also observing the student body are some familiar movie monsters, a trio that includes a Wolfman named Krakow (William Engesser), Dracula and Frankenstein's monster.

Judged by the undemanding standards of its own genre, Bare Mountain is a successful nudie. Prudence's classmates are attractive women with neatly proportioned bodies that generally wear nakedness well.

Under the direction of veteran sexploitation filmmaker R. Lee Frost, they move through their paces with reasonable spirit and grace. Given "a silly little comedy" and a comely cast to display, Frost does the job he was paid for: he keeps the camera in focus and makes pretty, Playboy-pure pictures.

ADDED TO THE BILL is The Penthouse, writer-director John Collinson's under-rated adaptation of C. Scott Forbes's Pinteresque stage play The Meter Man.

Originally released in 1967, the British home-invasion thriller was unable to survive its own lurid promotional campaign. Critics attacked its mannered unreality and supposed sadism. The public just stayed away.

A medieval morality play in modern dress, The Penthouse is more parable than pornography. It deserves a second look.

The above is a restored version of a Vancouver Express feature and review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1970. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Just as Famous Monsters of Filmland, originally published in 1958, claimed to be "the world's first monster fan magazine," The House on Bare Mountain is often cited as "the first Monster Nudie flick." Both reflected the changes that were taking place in the pop culture of their day. Lew Young hoped that adapting the programming format of his single-screen suburban movie house to such changes would save his business. As it turned out, the threat to his livelihood was part of a larger trend, one that was bringing an end to the era of independent film exhibition. Multiplex movie houses and home video were on the horizon. Chain theatre operations devastated locally-owned neighbourhood cinemas in much the same way that agribusiness corporations destroyed the family farm. In the above feature, I noted that Young was staking his future on "the only product that the major chains wouldn't touch — the exploiters." The fact that there was an audience for "exploiters" was not lost on the majors, and Young's competitive advantage was short-lived. The Surf Theatre closed permanently in 1972.