Friday, July 16, 1982.

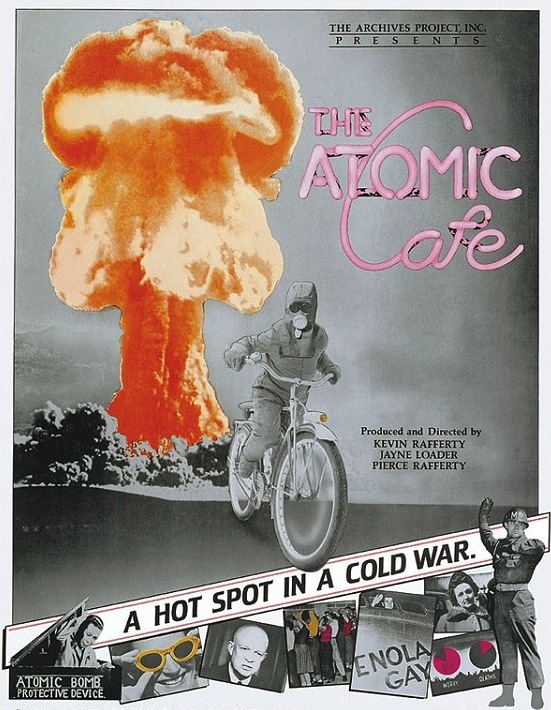

THE ATOMIC CAFE. Archival footage documentary. Music coordinated by Rick Eaker. Co-produced, co-directed and researched by Pierce Rafferty. Co-produced, co-directed and edited by Jayne Loader and Kevin Rafferty. Running time: 92 minutes. Mature entertainment.

THE BOMB. NUCLEAR HOLOCAUST, the horror of instant incineration at Ground Zero and the slow, painful wasting away of the rest of the human race.

Scary stuff.

Fortunately, The Atomic Cafe is not really about The Bomb. Despite its anti-nuclear sponsorship, this American-made documentary is neither a strident nor an obvious polemic.

It is, rather, a slick, informative and surprisingly entertaining bit of cultural anthropology. It shows us how Americans created, then learned to cope with, the atomic age.

The project brought together freelance journalist Jayne Loader with filmmakers Kevin and Pierce Rafferty. For the better part of five years, they sought out and edited archival footage, assembling freely-available, mostly government-sponsored material into a mosaic of the times.

The atomic age began with the August 1945 destruction of two Japanese cities, Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The U.S. then enjoyed a nuclear monopoly until, with the explosion of a Soviet device in 1949, there was suddenly the threat of a Third World War.

In the 1950s, with A-bomb tests covered on TV and the kids singing songs such as 1953's Atomic Love and Atom Bomb Baby (1957), an Arco, Idaho restaurateur named his diner The Atomic Cafe.

The filmmakers choose to tell their story without narration, using only the words, music and images of the period. While it's possible to read any number of messages into their work, it's just as easy to see The Atomic Cafe as an accomplished exercise in the time-honoured art of movie montage.

For the most part, the picture is chronological, moving from the end of the war through the civil defence-conscious years of the 1950s. Those of us who grew up then will recognize those strangely distant desert tests and the fallout shelter drills as part of the world we lived in.

As a coda, the film shows us an atomic attack, a reprise of much of the previously seen what-to-do-in-case-of footage set to the tune of a Liszt rhapsody. Like We'll Meet Again (sung at the end of director Stanley Kubrick's 1964 black comedy Dr. Strangelove), the effect is artful and even soothing.

What the filmmakers recognize is that people do not live in a permanent state of fear. The Bomb has been with us for 37 years now [in 1982], and we all managed to survive that first, terrifying decade of its existence.

Just as the wartime generation can look back upon old Dubya-Dubya-Two as "the best years of our lives," we bomb babies can't help but feel a tug of nostalgia for the 1950s, Intentionally or not, The Atomic Cafe feeds those feelings.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1982. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: On May 27, 2016, Barack Obama made history. He became the first sitting U.S. president to visit Hiroshima and, not unexpectedly, there were those quick to characterize his carefully worded speech at the city's Peace Memorial Park as "an apology." It was not. Still, sadly, there exists in the U.S. a cluster of implacable A-bomb advocates. In common with holocaust deniers and global-warming skeptics, they are deaf to the accumulation of historical research and scientific fact. They firmly believe that the mass murder ordered up by wartime President Harry Truman was justified, and they endlessly repeat the discredited arguments that the bombings were "necessary," that they "saved lives" and "shortened the war." They ignore the fact that the Second World War's U.S. military leaders — a group that included the Generals Eisenhower, Marshall and MacArthur as well as the Admirals Leahy, Nimitz and Halsey — all said that using the A-bomb was unnecessary. The record also shows that many of the scientists who built the bomb were against its use. In June 1945, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist James Franck met with six of his Manhattan project colleagues to draft what became the Report of the Committee on Political and Social Problems. Remembered as "the Franck Report," it argued the humanitarian case for not using the bomb on civilians, and recommended that it be "demonstrated" to the nations of the world in some remote location. It also predicted the nuclear arms race. The Franck Report was delivered to the Interim Committee, an eight-man group of politicians and government officials selected by Truman to advise him on the use of the new bomb. That group, chaired by the U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson, made the decision that resulted in the bomb's use and the cultural fallout examined in The Atomic Cafe.