Tuesday, May 1, 1973

NAPOLÉON. Music by Bob Vaughn. Written, produced and directed by Abel Gance. Running time: 332 minutes. General entertainment.

SAN FRANCISCO — In April, 1796, a charismatic Corsican named Napoléon Bonaparte led the newly created Grand Army of France into the fertile valleys of ltaly. Last Thursday night [April 26, 1973], under the direction of Able Gance, the Grand Army rose up and triumphed again, overwhelming and enthralling an audience of Bay Area film sophisticates.

If Gance's film had been new, its West Coast premiere would have been a major movie event. As it is, his Napoléon was made 46 years ago [in 1927]. It was cheered, hailed and almost immediately lost. Its restoration and exhibition qualifies as the major movie event of the year and, so far, the most important film happening of the 1970s.

Napoléon, with an original running time of five hours, was one of the legendary "lost" masterworks of world cinema. The single most ambitious and innovative film of the silent era, it ranked with D. W. Griffith's 1916 epic Intolerance (1916) for physical size, and with his Birth of a Nation (1915) for thematic scope. It shared with Erich von Stroheim's original 10-hour Greed (1924) the distinction of having been mutilated and lost forever.

For years film historians, none of whom had actually seen the original, have enthused about the revolutionary techniques Gance pioneered in his cinematic masterpiece. They wrote about his use of subjective photography, of the effects he achieved with hand-held cameras and of cameras mounted on horses, guillotines and giant pendulums. They described his rapid cutting, fluid editing, symbolic juxtapositions, and his experiments with colour, 3-D and a process he called Polyvision.

Polyvision has been the source of greatest fascination, because it was at once the inspiration and precursor of the wide-screen revolution of the 1950s, and because it appeared to have been actively suppressed by the film industry of the day. Basically, it was a multi-screen process. Early in the film, it shows up as a split screen with two, four, and, at one point, nine separate images sharing the frame.

For the last reel, Napoléon's speech to the Grand Army and the invasion of Italy, the screen triples in size, and Polyvision becomes the original Cinerama, a triptych with three projectors running simultaneously to fill the vast screen.

According to Gance (interviewed by British film historian Kevin Brownlow for his 1968 book The Parade's Gone By), "Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer bought (Napoléon) for a very great sum just to lock it away. They said to themselves, 'If we put out these triptychs, we'll cause a revolution, and we'll complicate the whole structure of the business. We'll have to use three projectors and three cameras each time we shoot . . . No, let's put an end to it before it starts.’ ”

The complete Napoléon premiered in the Paris Opera on April 7, 1927. It played there and in seven other European cities before being locked away by M-G-M. Immediately chopped from 23 to 17 reels for its subsequent European release, it was never shown properly in the U.S. The version shipped to North America was an eight-reel (90-minute) travesty.

In his book, Brownlow pointed out that in 1927 studios like M-G-M were already in the midst of the sound revolution, and probably felt that they had enough headaches. He did, however, lament the loss of the original film.

Then a wonderful thing began to happen.

Brownlow began receiving word of hitherto-unknown prints of Napoléon in various film archives and private collections. He decided to make an attempt at restoration, piecing the five hours back together scene by scene. His finished print, with triptych back in place, runs (by Brownlow's own estimate) a mere one minute shorter than the Paris original.

Thus Napoléon, restored and resplendent, finally made it to North America, honoured with a gala World Premiere on April 14 at the American Film Institute Theater in Washington’s John F. Kennedy Centre for the Performing Arts. It was shown for the second time last week in San Francisco's Avenue Theater under the sponsorship of the Pacific Film Archive.

In his interview with Brownlow, Gance described the film's original Paris premiere: "De Gaulle was in the audience, as a young captain. Malraux told me he stood up and waved his great long arms in the air and shouted 'Bravo, tremendous, magnificent!' He never forgot the film."

Nearly half a century later, a San Francisco audience reacted with similar enthusiasm, applauding, cheering and actually calling for an encore of the spectacular final scene. And that after five hours of sitting in a theatre!

Magnificent, spectacular, a classic, a masterpiece — in this case, all of the adjectives apply. Tomorrow I'll talk about the film itself.

Wednesday, May 3, 1973

SAN FRANCISCO — Over the years, the story of Napoléon Bonaparte, the Little Corporal who forged a Continental empire from a revolution-torn republic, has proved irresistible to filmmakers. The list of distinguished actors who have brooded through the part includes Claude Rains, Charles Boyer, Herbert Lom, Rod Steiger and Marlon Brando.

Directors, too, have brooded upon the career of the Corsican, the most recent example being Soviet filmmaker Sergei Bondarchuk. Beginning his narrative with a $100 million version of War and Peace (1966-67), Bondarchuk went on to film Waterloo (1970), both movies recording epic French defeats. For the last five years, Stanley Kubrick has been announcing that his "next" project will be a film called Napoleon.

Kubrick will have to go a long way, though, to equal the magnificence of Abel Gance's 1927 epic, Napoléon. The master craftsman of the French silent era, Gance produced a five-hour encyclopedia of spectacular cinema and a compendium of filmic effects, all supporting his view that Napoléon was France's greatest hero, and one of the most insightful players ever to step upon the world stage.

Gance tells his story episodically, using a dozen major vignettes. He begins with the boy Napoléon at the military academy of Brienne. As played by Vladimir Roudenko, Napoléon is a serious, self-isolated lad, plagued by devils of destiny and ever on the edge of outrage.

A Corsican being schooled in France, he takes violent offense when a thoughtless instructor refers to his homeland as "half-civilized." Outside the classroom, he thinks nothing of taking command of a vastly outnumbered garrison under siege in a snow fort, or of singlehandedly taking on an entire dormitory when he thinks that he has been wronged.

Gance displays his visual virtuosity and technical inventiveness from the start. The film's opening sequence is the cadets' snowball fight, a scene used to introduce Napoleon as a calm, decisive leader who not only displays craft and competence, but virtue as well. Gance throws his audience into the midst of the battle by sending his camera charging across the snow along with the combatants.

As the tempo of the fight increases, Gance reflects the swiftly flowing adrenalin with ever-briefer shots, until the effect on the screen is almost stroboscopic. The course of the battle is written on the young Napoléon's bloodied face, seen often early in the action and superimposed over it when the fighting reaches a fever pitch.

The scene is a breathtaking bit of action cinema. It is also designed to make dramatic points. In it, Gance underlines Napoléon's personal charisma, a quality not immediately apparent to his schoolmates, the sons of the "better" classes, but instinctively grasped by kitchen scullion Tristan Fleuri (Nicolas Koline) who cheers the lad on.

Later in the film, Fleuri, Gance’s representative of the common people who both respected and loved their emperor, will be on hand to watch Napoléon win his first great military victory, the defeat of a combined English, Italian and Spanish force holding the city of Toulon. Even later, Fleuri's daughter Violine (Annabella) will become a maidservant to Joséphine (Gina Manès), and literally worship a wooden doll representing her mistress's husband.

A lonely boy full of deep thoughts and lofty ambitions, Napoléon keeps an eagle in the dormitory attic. When a couple of malicious pranksters release his bird, the enraged Corsican asks his barracks mates, one after the other, who did it.

None will own up. Declaring that all are then responsible, Napoléon attempts to thrash the lot. The resulting scene, a pillow fight, introduced the first of Gance's Polyvision techniques — multiscreens within the same frame. At the battle's height, there are nine separate images on screen, all full of flying feathers.

Despite one teacher's declaration that “he will go far — he is made of granite heated on a volcano," the young justice seeker is exiled from the dorm. In one of the film's most striking images, he chooses to sleep on the barrel of a cannon. Comfort, in the form of a blanket, is brought to him by the scullion Fleuri. Destiny, in the form of his eagle, comes to rest on his shoulder.

If Gance had stopped right there, he would have earned an honoured place among pioneer filmmakers. In his handling of the Brienne sequence, he displays more cinematic flair and more epic sense than a stodgy old hack like Cecil B. De Mille did in an entire career.

Gance, however, was just warming up. After proving that he could make a snowball fight seem as important as a Biblical battle, he jumps ahead nine years to present his own romantic, but thoroughly arresting, vision of some genuinely epic moments in Revolutionary French history.

From the classroom, he moves to the Convention hall and introduces the three "gods" (his description) of the Revolution: Marat (Antonin Artaud), Danton (Alexandre Koubitzky) and, the only character in the film to radiate as much charisma as Napoléon, the dark-spectacled Robespierre (Edmond Van Daëlle)

A book could be written (and probably will be by British film historian Kevin Brownlow, the editor who restored Napoléon to its original five-hour form) describing the scene-by-scene wonders with which Gance has filled his film.

For the rest of the movie, he piles great moments one upon the other: the introduction of the battle hymn La Marseillaise to the Convention, the Terror, Napoléon's return to Corsica, his flight from Corsica, his victory at Toulon, his proscription, his infatuation with and marriage to Joséphine and, finally, his Italian campaign, waged across a triple-width screen.

Quite frankly, up until he meets Joséphine, Napoléon (played as an adult by Albert Dieudonné) is a bit of a lead soldier. He appears to have two expressions — hat on, and hat off.

Gance achieves a bit of unintentional humour when, during his sojourn on Corsica, Napoléon learns that his people are about to be sold out to the English. ''What are you going to do?" asks his mother.

Pausing for a moment, the thus-far impassive Napoléon removes his hat and says, "I'm going to ACT, Mother."

And he does, lighting out into an action-filled adventure sequence that blends the swashbuckling elements of Zorro and Robin Hood with the sort of visual flair that, in the sound era, would become the trademark of John Ford.

With the introduction of sound, Gance reworked footage from his original film three times. In 1934, he prepared a two-hour stereophonic sound version. Adding dialogue proved no difficulty, because the silent actors had worked from an actual script. In 1954, a version was released that reduced the original triptych scenes to a thin line across a single screen.

A third sound version played the New York (and later the San Francisco) Film Festival. Despite its incompleteness, the American audience recognized the beauty and genius of the project. The fully-restored Brownlow print was the highlight of the American Film Institute's opening festival last month [April, 1973] in Washington, D.C.

Last week, San Francisco had the pleasure of giving Napoléon its second North American showing. The presentation was sponsored by the Pacific Film Archive, headquartered at Berkeley's University Art Museum.

Screened in the 950-seat Avenue Theater, Napoléon was superbly accompanied by Bob Vaughn, a master of the Mighty Wurlitzer organ, who managed to construct a score after only one preview of the lengthy film.

In restoring Napoléon, Brownlow has assured for Gance, still alive and active in his 84th year, a place in the pantheon of film artists. He has assured himself a place as one of the cinema's major benefactors.

The above are restored versions of two Province reports by Michael Walsh originally published in 1973. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Monday, June 14, 1982.

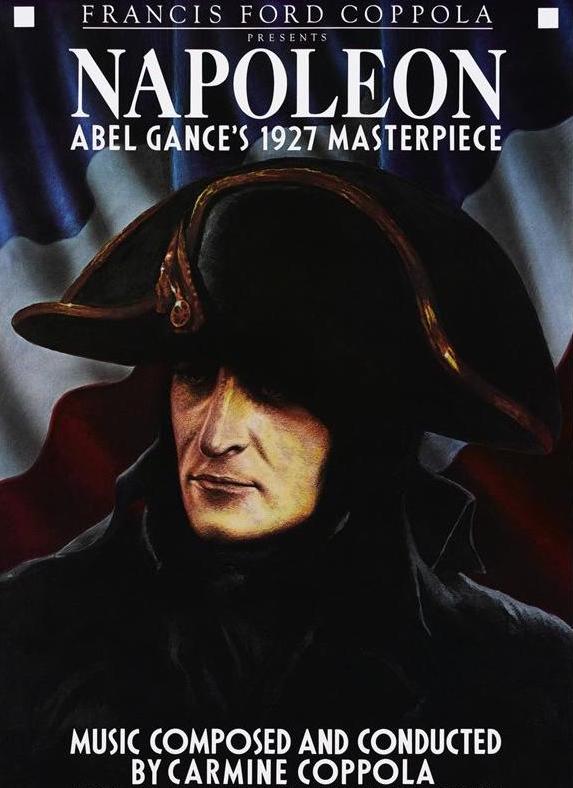

NAPOLÉON. Music by Carmine Coppola. Written, produced and directed by Abel Gance. Running time: 235 minutes. General entertainment.

IN APRIL, 1796, A CHARISMATIC Corsican named Napoléon Bonaparte led the newly created Grand Army of France into the fertile valleys of Italy. Early this year [1982], under the direction of Able Gance, the Grand Army rose up and triumphed again, overwhelming and enthralling an audience of New York film sophisticates.

Gance’s picture, screened eight times in Manhattan’s Radio City Music Hall, was a major movie event. Originally scheduled for three performances, the run was extended by genuine popular demand. Said the New York Times in a headline, “Napoléon Is Hottest Ticket in Town.”

The source of the excitement was a 55-year-old silent film, a landmark movie that was presented to the public with all the trimmings by its distributor, Francis Ford Coppola’s Zoetrope Studios. “When my father was a kid,” said Coppola, “all the movie theatres had orchestras.

"I imagined what it would be like to see Napoléon with a live orchestra.” The film and the experience of it so thrilled New York that Coppola decided to take his show on the road. Toronto saw it in March, and Vancouver gets its chance July 5 to 11 [1982], with the Vancouver Symphony providing the musical accompaniment.

On screen at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre will be Napoléon, one of the legendary “lost” masterpieces of world cinema.

[This preview feature was written nine years after my two dispatches from San Francisco reporting on the Pacific Film Archive's screening of British film historian Kevin Brownlow’s Napoléon restoration. From this point, with the exceptions noted below, the published text was a near verbatim restatement of the material included in the two 1972 items posted above.]

. . . On April 14, 1973, it was honoured with a gala premiere in Washington’s John F. Kennedy Centre for the Performing Arts. And then it was on to San Francisco for showings under the sponsorship of the Pacific Film Archive.

It was there that Coppola first met the Little Corporal from Corsica. Years earlier, Gance had described the film’s Paris premiere to Brownlow. "De Gaulle was in the audience, as a young captain.

“Malraux told me he stood up and waved his great long arms in the air and shouted, 'Bravo, tremendous, magnificent!' He never forgot the film." Nearly half a century later, the director of The Godfather dreamed of recreating that excitement . . .

The current Brownlow version attempts to recreate the immediacy of the original. Oscar-winning composer Carmine (Godfather II) Coppola has written a full symphonic score, and its public presentation is being treated as a once in-a-lifetime concert event.

Locally, the premiere is being held as a benefit for the financially troubled Pacific Cinematheque. Tickets, selling for $35 to Cinematheque members and $40 to non-members, include a gala reception following the July 5 [1982] performance.

Admission for the remaining six days of the run is scaled from $19.25 to $23.75 per seat. Bookings are through the Vancouver Ticket Centre.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1982. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Stanley Kubrick never got it together to shoot his version of Napoleon. It was the biggest film he never made because, ultimately, his financiers refused to fund it. The U.K.-based American director put years of work into research, scouting locations and even cutting a deal with Romania to use its army to stage the battle scenes, before he finally shelved it. It wouldn’t be a total loss, though. In 1973, Kubrick went on location in Ireland to shoot Barry Lyndon. A period piece, his adaptation of the 1844 novel by William Makepeace Thackeray benefited from his exhaustive study of the historical period.

Kevin Brownlow did write another entire book on Napoléon. A year after the Coppola “presentation” of the movie was shown in Vancouver, Brownlow’s 304-page Napoléon: Abel Gance's Classic Film, was published by Jonathan Cape (1983). Not surprisingly, his work remains the definitive word on the subject. Then there was the music. If Gance’s picture was lost for a time, the orchestral score that accompanied its 1927 premiere at the Paris Opera House appears to be gone for good.

Commissioned for the occasion, it was written by modernist Swiss composer Arthur Honegger (1892-1955). To date, musicologists have been unable to locate an original manuscript or cue sheets from his work. As a result, the Brownlow restoration featured a pastiche of new and classical music assembled for the occasion by London-based composer Carl Davis. A soundtrack recording was issued on a Chrysalis LP in 1983, with Davis conducting London's Wren Orchestra. In North America — which included the Vancouver screenings noted above — Napoléon was accompanied by the cartoon-Iike score written by Carmine Coppola. Issued in 1981 as a Sony Music LP, the soundtrack recording features the composer conducting the Milan Philharmonic. A copyright dispute ensued in which the Coppola family claimed to own the copyright to the film. The legal maneuvering went on for more than 25 years, before finally being resolved in 2008.

But wait, as they say in late night TV ads, there’s more. Though Honegger’s 1927 score may have vanished, a concert suite that induced eight pieces arranged by the composer was published that same year by Éditions Francis Salabert in Paris. With about 22 minutes of music to work with, Honegger’s Paris Conservatoire pupil Marius Constant — best known to us as the composer of TV's Twilight Zone theme — wrote a new/old score for the picture. Napoleon - Abel Gance, labelled a “Film Soundtrack,” was a 1994 CD released by Erato Disques. Included are 54 minutes of Constant’s two-hour symphony.