Friday, June 5, 1992.

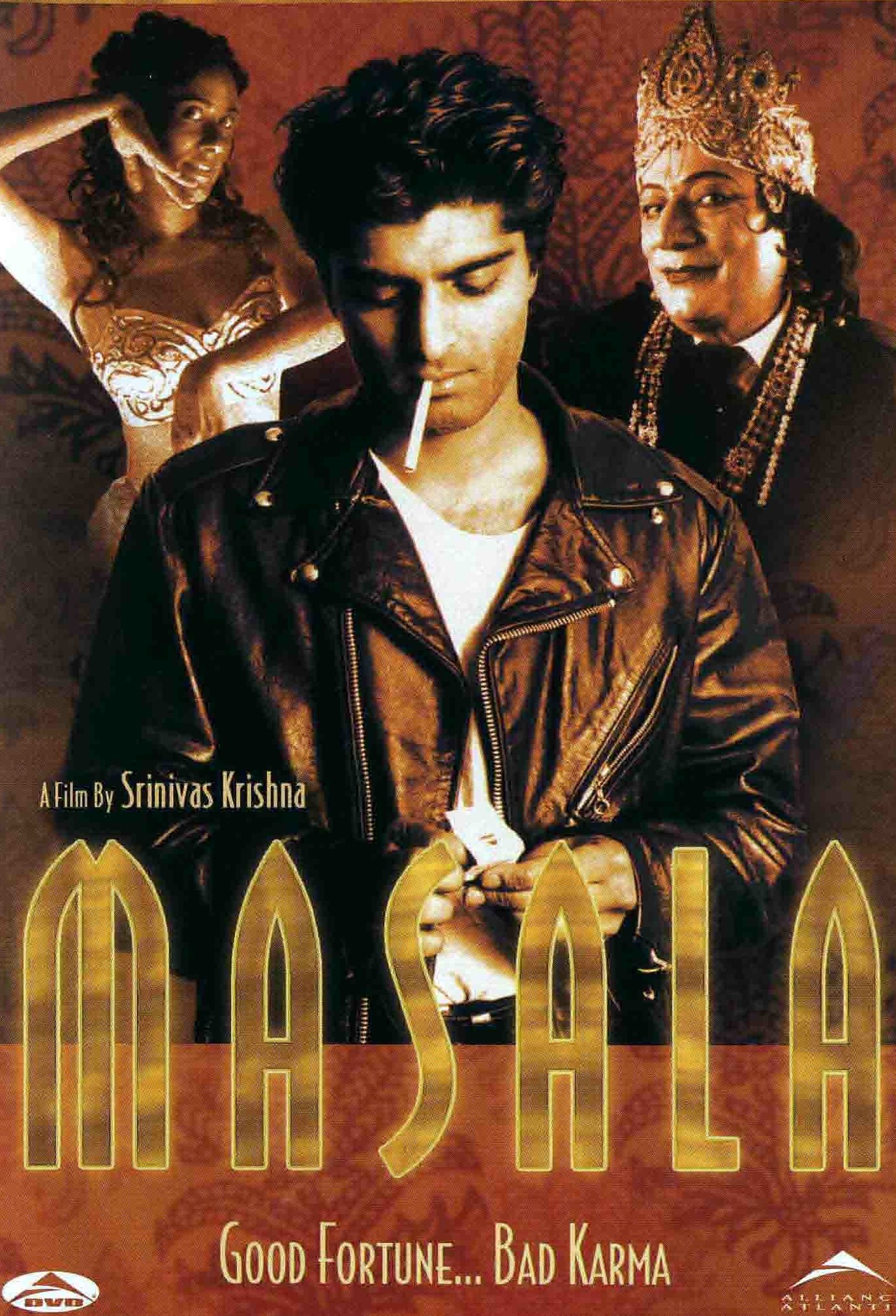

MASALA. Music by Leslie Winston. Written, produced and directed by Srinivas Krishna. Running time: 96 minutes. Rated 14 Years with the B.C. Classifier's warning: occasional nudity, suggestive scenes, coarse language and violence.

THE WORD "MASALA" ISN'T in the dictionary.

It does not appear in my Concise Oxford, nor in the five others that I checked. It does appear in movie titles, though.

In February, it was there in 1991's Mississippi Masala, Mira Nair's gritty, insistent inter-racial love story. There, the word is defined for us in dialogue. Meena (Sarita Choudhury), a Uganda-born East Indian and the film's title character, calls herself "a mixed masala . . . a bunch of hot spices."

Now comes Masala, a compelling if uneven first feature from Indo-Canadian writer-director Srinivas Krishna. Raiding the cinematic pantry, he's cooked up a dish that defies simple description while challenging our taste.

His Masala offers us a blend of styles and themes. Set in Toronto, it's about such things as the immigrant experience, shifting values in Canadian society and traditional Indian movie-making.

Krishna's intention is to stir things up. He casts himself in one of the film's key roles, playing Krishna, an angry, unstable orphan with a violent history.

Worth noting here is the fact that India is a great filmgoing nation. Despite severe censorship and rigidly formulaic entertainment traditions, movies dominate the popular culture.

With Masala, writer-director Krishna displays a creative rebellion. Mixed in with the family humour and cheery musical production numbers are sex, scenes of full-frontal nudity, deliberate political satire and what looks like outright blasphemy.

It opens aboard Air India flight 421. Little brother asks dad why big brother isn't vacationing with them.

The inflight film is a Hindi fantasy. We see the blue-skinned Lord Krishna (Saeed Jaffrey) bantering with Balrama (Wayne Bowman) about their godly responsibilities.

The gods are bored. Then, suddenly, the plane explodes.

Five years later, young Krishna, the brother not aboard the doomed airliner, is at large in Toronto.

For the rest of the film, he interacts with the family of his uncle, wealthy sari merchant Lallu Bhai Solanki (Jaffrey in a second role). He'll also meet independent Rita Tikkoo (Sakina Jaffrey, Saeed's actress daughter), the daughter of poor but honest postal worker Hariprasad (Saeed Jaffrey in a third role).

In focusing on an Indian immigrant community, it follows in the path of such films as Britain's My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), the U.S. feature Lonely in America (1990) and, of course, Mississippi Masala. The wild card in this pack, Masala has Lord Krishna offering comment and occasional intervention.

Though concerned about the possibility of jurisdictional disputes with Jesus, the Hindu deity is more worried about "what happens to Indians when they go to foreign lands." He notes that "they lose their grace and composure."

The god is hectored by Granny Tikkoo (Zohra Segal), who calls him up on her VCR. "Make it like it was," she demands, "before we came to this land of supply-side economics and no-money-down real estate."

The take-no-prisoners approach to its material results in scenes that hit and others that miss. Its moments of brilliant inspiration make director Krishna's Masala a meal worth sampling.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1992. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: "There was a plane that blew up over the Atlantic, going back from Toronto and Montreal to Bombay. They suspected Sikh terrorists," Srinivas Krishna told Boston university film studies professor Roy Grundmann in a 1994 interview. "I knew people on that flight from the University of Toronto. Almost four years after that, I started thinking about the incident in terms of the question 'Can one really go home?' Home, it seems, is not the place one has left. The problem is the search for authenticity and origin." From Chennai, the capital of India's Tamil Nadu state, Krishna was a child when his parents immigrated to Canada in the 1970s. He studied Art and Art History, graduating from the U of T in 1987. Two years later, he added an MFA in Film and Cinematography from Philadelphia's Temple University. Masala, his debut feature, was the product of — dare I say it? — an explosive young talent with much to say, attempting to say it all at once. In an essay on Krishna written in 2010, Toronto-based reviewer Cameron Bailey notes that "in 2002, the British Film Institute conducted an online poll that voted Masala to be the Best Film of the 20th Century from the South Asian Diaspora."

Not considered a mass-market movie in 1992, Masala received only limited distribution. Krishna made two subsequent theatrical features — Lulu (1996), a more conventional drama that tells the tale of a Vietnamese mail-order bride, and the 2009 documentary Ganesh, Boy Wonder. His primary work in recent years has been in television and interactive digital media. In 2012, he founded Toronto's AWE Company Ltd., a research and development studio focused on "patent-pending technologies and tools that enable immersive, interactive, augmented and virtual reality experiences for mobile audiences – the cinema of the future." In October 2015, AWE beta-tested what it calls "the Largest Virtual Reality Experience in the World" at the nine-acre Fort York National Historic Site in downtown Toronto. With its launch promised this summer (2016), the Fort York virtual tour promises to equip visitors with a device that allows them to "see" into the past of the histroric real estate immediately in front of them.

Masala remains a controversial achievement. As Krishna told Grundmann in 1994, subsequent investigations blamed Sikh extremists living in British Columbia for the destruction of Air India Flight 182. Evidence gathered by police and security agents said that the bomb used to destroy the Boeing 747 had been built in Duncan, B.C., packed into a suitcase loaded aboard a Vancouver-to-Toronto CP Airliner, then transferred to the Air India flight. The largest mass murder in Canadian history, its story was first detailed in The Death of Air India 182, published in 1986 by my Province colleague, investigative reporter Salim Jiwa. The Vancouver Sun's Kim Bolan marked the 20th anniversary of the tragedy with the publication of Loss of Faith: How the Air-India Bombers Got Away With Murder (2006). A year later, Jiwa collaborated with newsroom colleague Don Hauka on Margin of Terror: A Reporter's Twenty-Year Odyssey Covering The Tragedies of the Air India Bombing, the most complete telling of the story to date.