Wednesday, March 23, 1977

THE JAZZ SINGER. Adapted for the screen by Alfred A. Cohn, from the stage play by Samson Raphaelson. Titles by Jack Jarmuth. Music by Louis Silvers. Directed by Alan Crosland. Running time: 88 minutes.DON JUAN. Written by Bess Meredyth. Titles by Walter Anthony and Maude Fulton. Music by William Axt and David Mendoza. Directed by Alan Crosland. Running time: 110 minutes.

SEATTLE — WITHIN THE BIG film studios the response was uniformly negative. The critics were divided. The public, however, loved it.

Sound. Welford Beaton, publisher of the Hollywood-based journal Film Spectator, went directly to the heart of the issue. "The Jazz Singer definitely establishes the fact that talking pictures are imminent.

"Everyone in Hollywood can rise up and declare that they are not," Beaton wrote, "and it will not alter the fact . . . As speaking pictures become better known, the public will demand them, and producers who do not keep up with a public demand will be forced out of business by those who do."

Fifty years ago [from 1977], the movie industry was shocked out of its silence by something called "the Vitaphone." Acquired by Warner Brothers from the Bell Telephone Company's research laboratories, the Vitaphone was a sound-on-disc process that provided aural accompaniment to a film's visual images.

The feature film that introduced the Vitaphone was a lavish costume epic, 1926's Don Juan. Fourteen months later, in 1927, Warners released The Jazz Singer, and the sound revolution was all but won.

This month [March 1977] is the golden anniversary of the arrival of the Vitaphone in Seattle. To celebrate the occasion, Second Avenue's Moore Egyptian Theatre has brought back both films for a special week-long run.

Don Juan is the real surprise. A full-blown spectacle, it stars John Barrymore, whose debauched, world-weary Juan seems to deliberately parody all-American swashbuckler Douglas Fairbanks.

The setting is Renaissance Rome during the reign of the bloody Borgias. Our not-so-heroic hero is stalked by Cesare (Warner Oland), who wants him in his dungeon, Lucrezia (Estelle Taylor), who wants him in her bed, and a Borgia kinsman named Donati (Montague Love), who wants him on the end of his sword.

Made with tongue in cheek — at times it seems as if the villains are stacked six deep — the film eventually turns Juan into a conventional good guy. The only woman in Rome not available to him is the virginal Adriana (Mary Astor).

Juan is smitten. "My soul has been asleep," reads the florid title card. "You have awakened it." And you can just bet that that little awakening is going to get him into real trouble with the Borgias.

Storyline aside, Don Juan provided its premiere audience with an example of how sound could be used to heighten the effect of a film. Though the accompanying discs provided mostly music, they also heard the tolling of bells, knocking upon doors and, most memorably, the swish of swords as Juan and Donati squared off for their duel to the death.

The Jazz Singer took the process two steps further. It is remembered not only as the first talkie, but as the first movie musical.

A modern-dress drama, it is the story of Jack Robin (born Jakie Rabinowitz), a cantor's son banished from his father's house because he insists on singing "raggy time" music. Schmaltzy and sentimental, it was a hit Broadway play that Warner Brothers acquired along with its stage star, George Jessel.

Jessel, a New York-born vaudevillian, remains a footnote to film history because, when he found out that Warners planned to have sound sequences in the film, he held out for more money. He was promptly replaced by another vaudevillian, one named Al Jolson.

Jolson, described in the film as a singer "with a tear in his voice," was an irrepressible performer. Although the film's script called for no spoken dialogue, once the Vitaphone recording discs were moving, there was no way to stop them without ruining the entire take.

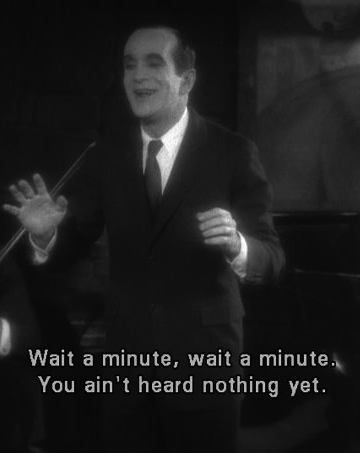

Once Jolson started, there was no stopping him, either. During his first number, he grinned down at his coffee house audience and ad-libbed the now famous "wait a minute, wait a minute. You ain't heard nothing yet!"

A film intended to have only background music and seven synchronized singing interludes — virtually all of the dialogue is on title cards — had suddenly become a "talkie." A second dialogue scene, one in which Jakie tells his mother Sara (Eugenie Besserer) how much he loves her, was added, and the power of sound to move an audience was confirmed.

Musically, the film has no consistency. Arranger Louis Silvers, borrowing from sources as diverse as Tchaikovsky and Tin Pan Alley, mixed it all together and hoped for the best. The best, of course, are the ten synchronized songs, six of them sung by Jolson.

Under the direction of Alan Crosland (who, a year before, brought Don Juan to the screen), The Jazz Singer builds to one of the all-time great tearjerker endings. Will Jack/Jakie miss his big Broadway premiere to replace his sick and dying father in the synagogue on the Day of Atonement?

Will this 50-year-old scene wring tears from an audience in 1977?

You bet it will.

In the opulent old Moore Egyptian, it's 1927 all over again. A landmark revival, The Jazz Singer is on view through Saturday [March 26, 1977].

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1977. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Once billed "the world's greatest entertainer," Lithuanian-born song-and-dance man Al Jolson is today best remembered as the man who broke cinema's sound barrier. By the mid-1930s, though, he was as famous as Charlie Chaplin and, more to the point, the highest-paid entertainer in the U.S. Because he did a lot of that entertaining in blackface (quite acceptable in his own casually racist day), his performing reputation hasn't stood the test of time. He was the subject of a reverential 1946 biopic (The Jolson Story) and its sequel (Jolson Sing Again; 1949). Playing conservative Republican Jolson was a major breakthrough for actor Larry Parks, whose career would end two years later, when he was alleged to be a Communist and blacklisted by a terminally craven Hollywood. For me, the most memorable thing about Jolson was his his marriage to the Nova Scotia-born Ruby Keeler. They tied the knot in 1928, and she tolerated him until their divorce in 1940.