Monday, November 21, 1966.

HART HOUSE MAY NEVER BE the same. First, it was an exhibition of ["Garterbeltmania" painter] Dennis Burton's underbelly erotica in the Art Gallery. Now, it seems, comic books are taking over the Great Hall.Not to be outdone by the Art Committee's untouchable unmentionables, the Library committeemen have teamed with George Henderson's Canadian Academy of Comic Book Collectors, reserved the entire main floor of the House and are preparing what is billed as "the largest, most comprehensive display of comic books and comic art that has ever been assembled."

Comic books have come to an awkward, ungainly prominence in recent months, due in part to the emergence and acceptance of the "pop" culture movement. All of the attention has served to point up what a strange twilight life they have led up until now. Their history is virtually undocumented.

Since the first true comic book appeared — 1938's Famous Funnies — there have been but two "real" books devoted to them: Fredric Wertham's Seduction of the Innocent (1954), a searing indictment of crime and horror comics, and 1965's The Great Comic Book Heroes, Jules Feiffer's nostalgic history of the superheroes.

Both of the above books were written in the midst of renewed adult interest in the comics. The Feiffer book was born of enchantment; Wertham's book, of outrage.

Crime and horror comics were the dragons that psychiatrist Wertham's crusade sought to slay. He called them "primers for delinquency" and "tools of illiteracy" and he offered an impressive amount of clinical evidence to back up his charges. His revelations shocked the public, shook up legislators and led to the comic book industry setting up the self-policing Comics Code Authority, a giant blue-pencil agency that exists to this day [1966].

Canada, by contrast, was far more direct in its protection of public morals. Legislation passed through Parliament as early as 1949 banning the sale or importation of precisely the material that Wertham would lead an American protest against five years later.

Canada's comic book publishers immediately raised the cry of "censorship," and the Senate was roused to join battle in support of "freedom of the press."

The anti-comics bill was all but quashed when the publishers made their fatal mistake. They distributed examples of their wares to the members of the Red Chamber, and the honourable members were appalled. The Commons bill passed virtually unopposed.

A decade later, Feiffer's book lionized the comics, idolized their heroes and glamourized their creators. Feiffer was, of course, remembering a far different comic age, the pre-war age of innocence. His was a vision of the days when Clark Kent was a reporter for the Daily Star, Superman leapt and bounded rather than flew, and Batman was still a one-man show.

COM-EX, the Hart House Comic Book Exposition, promises to bring back all of these memories and a lot more besides. They value their show at $20,000 and have gone to the trouble of acquiring a Lloyd's of London insurance policy.

Although comic books have never gained recognition from the worlds of either art or literature, their defenders, the "comicollectors," insist that they represent an intimate marriage of both media.

Further, comic books are one of the few indigenously American contributions to world culture, reflecting, and in some ways shaping, the generations of children that read them.

Because comic books have been all things to all people, Hart House's COM-EX will attempt to tie together all the threads: entertainment and artifact, object of culture, communication, sentiment and nostalgia.

The one evening show, starting this Sunday at 7:30 p.m., is a free admission event, but tickets must be picked up from the Hall Porter.

The above is a restored version of a University of Toronto Varsity column by Michael Walsh originally published in 1966. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: I met George Henderson in September, 1966, while preparing a story for The Varsity on Toronto bookstores within walking distance of the the university campus. Although I was not a comics collector, I did submit a paper on Frederic Wertham's mid-1950s crusade against the comics for one of my second-year sociology courses. I did not mention it in my Varsity column promoting COM-EX, but I was a member of the Hart House Library Committee, the body responsible for organizing literary events for the U. of T. men's student union. Henderson, seeing an opportunity to bring some academic legitimacy to our mutual appreciation of comics, suggested displaying some of his treasures on campus. The result was a significant (if obscure) moment in Canadian comics history, one that shamelessly borrowed its name from the upcoming Montreal World's Fair, Expo 67. In May 1967, "Captain" George moved his "comicollector" headquarters from its seedy 227 Queen Street West location to new premises in the upscale Markham Street Village, a block of shops set aside for Toronto's crafts community by discount department store owner and arts patron "Honest Ed" Mirvish. Henderson's Memory Lane Books is remembered as Canada's first comics shop, and George himself is affectionately remembered as the man who championed their social value as art and nostalgia until his death in 1992 at the age of 62.

In 1966, Peter Gzowski was the entertainment editor of Canada's largest newspaper, The Toronto Daily Star. Because he'd been editor of The Varsity during his final year at the U. of T. (1956-57), he actually read our campus paper regularly. The day after the above column appeared in print, I received a telephone call from Gzowski asking if I would do a rewrite of the piece to run as a section front in Saturday's Star. "Sure,' I said, not realizing that in that moment the whole direction of my life had changed.

Saturday, November 26, 1966

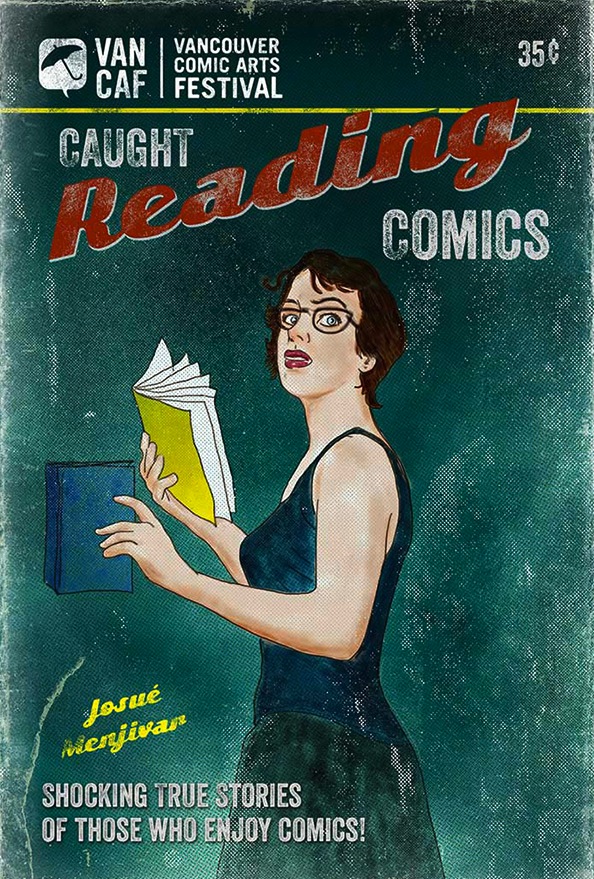

THE PULPY, UNDERGROUND WORLD of the comic book collector, a world of super-heroes, Sunday supplements and sentiment, will shed its traditional cloak of shyness (or should that read "furtiveness"?) tomorrow evening when the world's first all-inclusive public exposition of comic books and comic art is presented.

COM-EX, a joint project of Hart House at the University of Toronto and the recently formed Canadian Academy of Comic Book Collectors, is a landmark event for collector-members. For them it means that their hobby — comicology — has finally arrived and will, henceforth, be recognized as socially acceptable and culturally worthwhile.

Comic book collectors have been around for some 20 years —occasionally seen lurking about used book stores or bargaining vigourously at Boy Scout bazaars. They travelled singly and spoke softly. To them the panelled stories were an art form. Many of them were themselves artists, or had artistic aspirations.

Comic collecting was a lonely hobby at first. Few people admitted to being addicted. Occasionally, however, soulmates would meet and small covens would be formed. The early Fifties were the years of the cultists — those collectors fiercely dedicated to the work of a particular artist: Will Eisner's Spirit, Hal Foster's Prince Valiant or Milton Caniff's Terry and the Pirates.

Newsletters were circulated and grew into small magazines. The fans found themselves caught up in the mystery and magic of comic-book worlds. As their collections grew, their emphasis shifted from specific material to general ranges. The comic-book underground spread across the entire U.S., with collectors exchanging information, trading books, and even holding the occasional convention.

Then, suddenly, the secret was out. Superman was a Broadway star, the Merry Marvel Marching Society was marshalling America's campus crowd and Batmania swept the land. Comicollectors found themselves spotted in the harsh beam of the Bat-signal.

The unexpected attention has been viewed by collectors as a mixed blessing. The serious collector winces at the superficiality of "camp" and its faddist followers — for him the comic book is far more than an inane artifact.

Though it has never been formally recognized as either art or literature, the comic book is regarded by the collector as a loving marriage of both media. For him comics can be a genuine emotional experience — this largely based on their ability to call forth the shadows of the past.

On the other hand, the passing public fancy has also been a great boon. It has given a new sense of respectability to comic collecting, improved the collectors' lines of communication, and given impetus to potential collectors.

In the case of Toronto, it has served to provide a centre for the first organization of Canadian collectors and establish a market place for their trading.

The Canadian Academy of Comic Book Collectors, co-sponsor of the Hart House Exposition, is a fledgling organization. Members range from the middle-aged to minors, with George Henderson, owner of Queen Street's Viking Bookshop ("comicollector headquarters"), as its president.

Academy vice-president Michael McLuhan, son of the U. of T.'s Marshall McLuhan, is chairman in charge of COM-EX. Although its card-carrying membership is no more than 50, the Academy has been able to assemble a display worth an estimated $20,000.

COM-EX bills itself as the largest, most comprehensive display of comic books and comic art ever put together. The exposition's aim is to have a consolidating effect on the Academy itself by giving members an opportunity to display their very best and compare collections.

What distinguishes comic-book collectors is their vividness of memory. They can recall, and wish to retain, the very personal world that they discovered in comic books. It was a world that only the comics could create, only the comics could contain.

The above is a restored version of a Toronto Daily Star feature by Michael Walsh originally published in 1966. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: About 12 years ago, my daughter gave me a book with the cheeky title The First Time I Got Paid for It: Writer's Tales from the Hollywood Trenches. It reminded me that Peter Gzowski's 1966 phone call had resulted in my first paycheque as a writer. Actual money. I'd started university with a very different career path in mind — I was majoring in sociology — and journalism wasn't part of that plan. Working for The Varsity, which involved reviewing movies, was fun. Could I actually make a living having fun? It was Gzowski who started me thinking that maybe I could. To my shame, I never got around to thanking him for that.