Saturday, August 28, 1971.

EXCITEMENT CRACKLED IN THE air Friday morning [Aug. 27, 1971] as delegates to the World Shakespeare Congress gathered to hear an artist describe his vision.

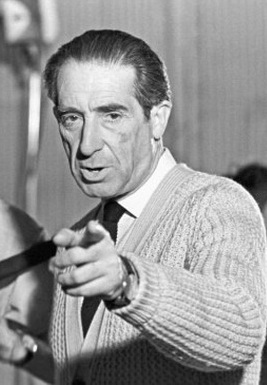

On the platform, blue-suited and just a bit nervous, was Grigori Kozintsev, the filmmaker responsible for the universally acclaimed Russian-language version of Hamlet. His film, made in 1964 as the Soviet Union's contribution to the Shakespeare quatercentenary, has already been screened twice for Congress members.

A print of his latest film, Koral Lir (King Lear), accompanied Kozintsev from Leningrad. A new movie, the Russian-language Lear has not been seen publicly outside the Soviet Union, but it is being screened privately for the Congress.

Not surprisingly, the subject of Kozintsev's paper was Hamlet and King Lear, Stage and Film. In it, he set off the cinema as a medium demanding a visual technique very different from that of the stage, and Shakespeare as an author whose own poetic realism transcends any location in time or space.

Cinema, he said, changes the stress of a play. The emphasis is on the visual rather than the oral and poetic textures have to be translated into film textures.

In a film, the characters are set in a landscape, he said. The landscape is thus able to bear a large portion of the poetic burden. It serves, not just as a location, but as the root of the action itself.

He cited the example of Raskolnikov, the tormented murderer in Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment. His character was inseparable from the image of the city of St. Petersburg, sweltering in the summer heat, Kozintsev said. The seething city was the materialization of the idea of the novel itself.

Shakespeare shares with Dostoevsky the feeling of space inseparable from time, with people perceptible within them "like flashes of summer lightning," he said. Concepts are inseparable from presentation.

For that reason, his film locations are chosen to place Shakespeare in a past that can easily become the future, creating a reality that is timeless.

Shakespeare, he said, is an endless labyrinth of connecting parts and every epoch must discover its own connections. "What I tried to do — what every age must — is read Shakespeare in the light of the present day," he said.

Prolonged applause followed Kozintsev's paper, and chairman Brian Parker of the University of Toronto offered the filmmaker "thanks for a most moving talk." The members of the critical panel were not without questions, though.

His Hamlet was not quite Shakespeare's, said Barbara de Mendonca of Rio de Janeiro's Escola de Teatro. Through a process of critical reduction Kozintsev had removed all the play's political comment, she said.

It was a moot point. It brought to the fore at least one of the underlying reasons for the electrical charge in the room. In a sense Kozintsev was "the man from the other side."

The same point, of course, could have been made equally well about either Tony Richardson's or Laurence Olivier's film version of the Danish court. Instead it was directed to Kozintsev.

The Russian, who had already made an eloquent film and an equally eloquent statement of his own artistic integrity, was asked if he wished to reply. Flustering slightly, he shook his head.

No.

The World Shakespeare Congress is jointly sponsored by Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia and the Canada Council. Sessions of the congress are being held on both campuses.

The above is a restored version of a Province feature report by Michael Walsh originally published in 1971. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Scholars continue to applaud the Soviet filmmaker. In his 2017 study The Shakespeare Films of Grigori Kozintsev, philosophy professor Michael Thomas Hudgens introduces his subject with a quote from Boston Globe critic Richard Dyer: “Paradoxically, the two most powerful films of Shakespeare plays were made not in Great Britain but in the Soviet Union.” Hudgens reminds his readers that Laurence Olivier, an Oscar winner for his 1948 screen adaptation of Hamlet, was among the first to heap praise on Kosintsev’s 1964 version, memorably declaring its star, Innokenti Smoktunovsky, as the cinema’s best Hamlet, better than his own portrayal. As for Kosintsev’s King Lear, it “has become an international treasure.”

Grigori Mikhailovich Kozintsev was born in 1905 in Kiev, at that time the administrative capital of the Russian Empire’s Kiev Governorate. The Russian Revolution (1917-1923) happened during his teen years, and in 1921 he moved to Petrograd (soon to be renamed Leningrad), where he studied theatre and organized a workshop called “Factory of the Eccentric Actor.” Filmmaking was the next logical step, and in 1924 he directed a silent comedy short called The Adventures of Oktyabrina. Kosintsev made his feature debut two years later with The Devil’s Wheel, a spirited crime drama.

We can trace Kosintsev’s interest in Shakespeare back to 1940, when he entered into a collaboration with novelist and Bard translator Boris Pasternak. The result was theatrical stagings of King Lear (1941) Othello (1943) and Hamlet (1954). A decade later, he brought his Hamlet adaptation to the screen. Before taking it before the cameras, he offered his thoughts on the project in his 1962 book Our Contemporary William Shakespeare (translated into English in 1966 as Shakespeare—Time and Conscience). In 1970, he completed King Lear, the feature he brought with him to Vancouver’s World Shakespeare Congress. In May 1973, Grigori Kozintsev died in Leningrad (soon to be renamed Saint Petersburg), just six months after his picture opened officially in the U.S. He was 68.

Congressional record: Reeling Back’s WSC archive consists of a Preview feature followed by my Opening report, a Tuesday report, a Wednesday report, a Thursday report, a Friday report, a First Folio feature about a family with links to both Shakespeare and Vancouver, a Saturday report, a Closing report, and my Summary feature.