Monday, August 9, 1982.

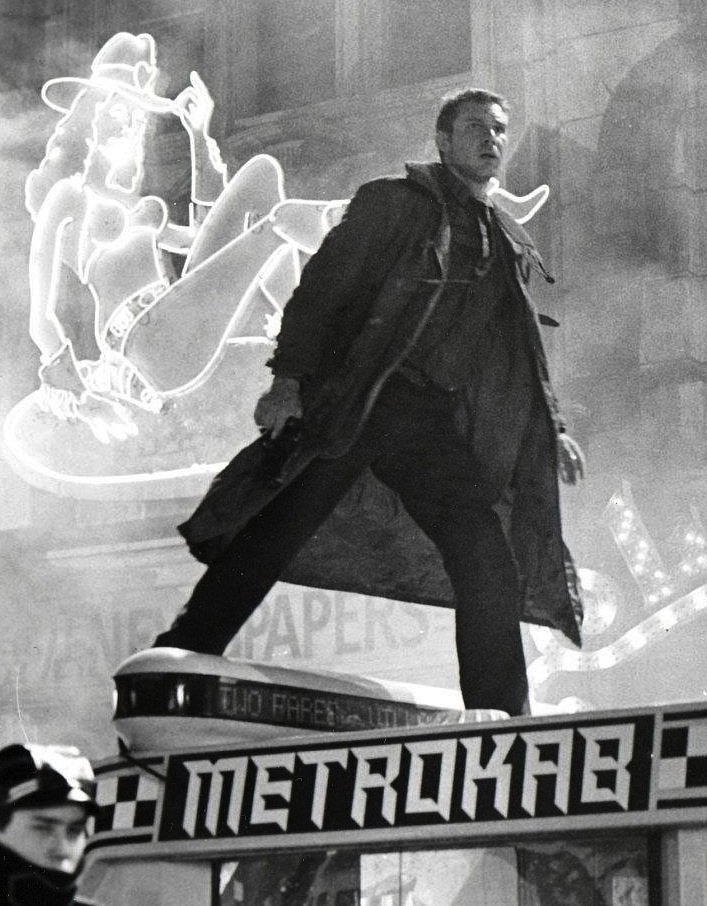

BLADE RUNNER. Written by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples. Based on the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) by Philip K. Dick. Music by Vangelis. Directed by Ridley Scott. Running time: 114 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: some gory violence.

On Friday, August 6, 1982, two science-fiction films opened in Vancouver, each one offering adventures set in a possible future. Reviewing them on the same day, I set the scene by referring to the much-feared possibility of a Third World War. My review of Australian director George Millier's The Road Warrior opened with the words:

"The war is over. Civilization as we know it has been destroyed . . ."

The second film reviewed, Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, began by echoing those words.

THE WAR NEVER HAPPENED. Civilization as we know it has evolved, stretching out beyond the Earth to colonize other planets. Our own world has become infested with overgrown, overpopulated mega-cities.

Helping man to extend his reach still further, corporate enterprise has created the replicant, a genetically-engineered creature that looks and acts like a human being. By 2020, replicant technology has become so good that its products are seen as a danger to real humans, and they have been outlawed on the home planet.

Even so, an occasional replicant will escape his deep space servitude, return to Earth and try to pass as human. Finding and killing them is the job of a specially trained policeman known as a Blade Runner.

Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) is a burnt-out, self-retired blade runner. When one of his former colleagues is killed during an investigation, Deckard is forced back into service to solve the murder.

Director Ridley (Alien) Scott is an atmosphere man. Formerly a successful producer of television commercials, he brings to the table a total environmental sense, telling his story as much through production design as through its script.

Adapted from the a pulp science-fiction novel by Philip K. Dick, Scott's Blade Runner is an intricately conceived near-future film noir, an absorbing, richly textured impression of life in the urban shadows. As in the noir classics of the 1940s, the city is seen as a dark, malevolent force in which an ethical man will be tested by his potentially destructive obsession with a beautiful, mysterious woman.

Deckard is on the trail of four top-of-the-line replicants led by super-android Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer). Tragic in their desire to experience real human feelings, these creatures are ruthless because they know that their life spans have been genetically limited by their corporate creator.

Deckard's job is made more difficult by the addition of a fifth replicant to his hit list. Rachael (Sean Young), executive assistant to the all-powerful Tyrell Corporation's Dr. Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel), is a model so advanced that she is unaware that she is not fully human.

Complicating Deckard's mission is the fact that the blade runner owes his life to her. Is it possible that he has fallen in love?

Into this superficially simple detective drama, Scott has built a complex set of moral questions. Visually stunning, his Blade Runner offers us an other-worldly nightmare that can be enjoyed as a one-time special effects show, or as a repeat-viewing look into a possible future.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1982. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Blade Runner was the first of nine feature films (to date) based on the works of science-fiction writer Philip Kindred Dick. Although he had found fame within the genre — he was guest of honour at the 1972 Vancouver Science Fiction Convention — the fortune that came from major motion-picture adaptations eluded him. Dick died of a stroke four months before Blade Runner's U.S. premiere. His paranoid visions have since inspired such accomplished directorial talents as Paul Verhoeven (Total Recall, 1990), Steven Spielberg (Minority Report, 2002), John Woo (the filmed-in-Vancouver Paycheck, 2003) and Richard Linklater (A Scanner Darkly, 2006). The complete Phil Dick feature filmography includes Quebecois director Christian Duguay's Screamers (1995), as well as Impostor (2001; Gary Fleder), Next (2007; Lee Tamahori), Radio Free Albemuth (2010; John Alan Simon) and The Adjustment Bureau (2011; George Nolfi). The single biggest beneficiary of Blade Runner's success was director Ridley Scott, who claimed at the time that he had never read Dick's novel. Scott later reissued the picture in a Director's Cut (1992), and again in a Final Cut (2007). Currently, Scott is reported to be working on a sequel, and has publicly asked Harrison Ford to reprise his role as Rick Deckard.