Friday, March 5, 1971

WHEN THE COMIC BOOK revolution came to town, it arrived not with a bang but with a whisper.

Quietly, last November, a new 40-page comic book stole into a handful of local stores and boutiques, including the bookstall at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

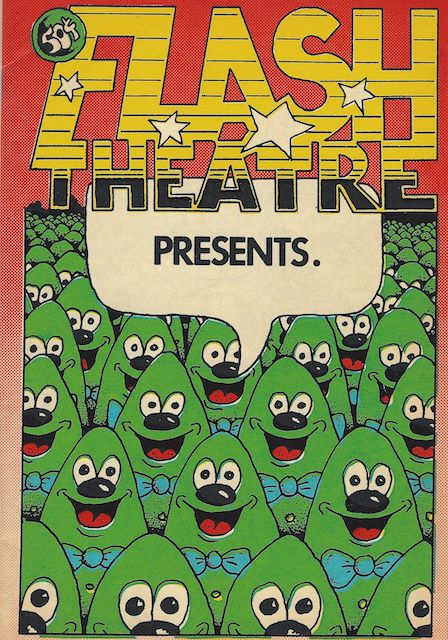

Although its cover featured a crowd of beaming cartoon faces, Flash Theatre Presents was not meant for the kiddies. Like dozens of new comic titles appearing out of Berkeley, San Francisco, New York and Chicago, it was printed in black and white and priced at 50 cents.

Produced more for fun than profit by a pair of Vancouver School of Art graduates, it was one of a new breed — an underground comic.

The label is misleading. Like underground movies and newspapers, underground comics are freely available to anyone with enough interest to seek them out. Most often, of course, they're sought out by young adults.

The comics are part of that loosely knit information network the news magazines like to call “the counter-culture." Irreverent and uninhibited, their effect is to reinforce the anti-traditional attitudes of the under-30s.

Underground comics arose for many of the same reasons as independent filmmaking. Young talent found the established commercial industry to be an ultra-conservative closed shop.

It was easier, and considerably more fun, to opt out of the system entirely and work alone. The new author-artists had grown up with comics and preferred exploring themes and styles that appealed to them rather than to a sales-conscious accountant in a front office.

The first underground comic, a blasphemous little pulp called God Nose, was produced in Austin, Texas in 1964. The idea didn't really get off the ground until Robert Crumb, a 24-year-old Cleveland greeting-card illustrator, quit his job.

With his wife Dana, Crumb took to the streets of San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury in 1968 to hawk his own privately-printed Zap Comix.

Zap was in tune with the street people. Its deranged-Disney style was just right for Crumb's peculiar mixture of "gags, jokes, kozmic trooths." It sold so well that Crumb was able to conclude a distribution deal with Berkeley's Print Mint.

Its success also inspired Print Mint owner Don Schenker to found a new tabloid comic magazine, Yellow Dog.

The comic book revolution had begun.

A pair of Texans, Jack Jaxon, creator of the original God Nose, and Gilbert Shelton, the mind behind Wonder Wart Hog and the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, migrated to San Francisco. Together they started Rip-Off Press, an artist's co-operative, to print and distribute their own comics.

A pair of Chicagoans, comic fan-magazine writers Jay Lynch and Skip Williamson, began putting out Bijou Funnies. In New York, a group of professional comic book artists formed the Save-Rose-Bimmler Society to produce Witzend, a magazine outside the authority of the commercial world's Comics Code.

Titles proliferated, each reflecting their authors' satirical preoccupations: Hydrogen Bomb and Biochemical Warfare Funnies, Conspiracy Capers, Insect Fear, Feds'n'Heads, Plunge into the Depths of Despair, Adventures of Jesus, Radical America, Spiffy Stories and others with racier names,

Despite their nasty titles and gloomy topics, most of the comic creators took tremendous joy from the act of creating something visually. The quality of their draftsmanship ranged from childish to stunningly beautiful. Seldom are they dull or predictable.

The artists created their own free world by becoming their own editors and publishers. But, because they recognize no codes, regulations or restraints, the underground comics often wallow in unabashed smut and general tastelessness.

Until now, no Canadian dealer has been sure enough of their local legal status to import the U.S. product. The major distributor in the Pacific Northwest is Underground Arts Unlimited, a friendly little bookstore on Seattle’s First Ave.

Vancouver's own Flash Theatre Presents is the brainchild of a pair of movie animators, Mal Hoskin, 24, and Dave Roberts, 22.

"I'd always thought of producing a book of drawings," Hoskin says. The idea of a comic seemed far-fetched, though, until he finally checked on the price.

College Printers, the press that turns out the Georgia Straight, offered to turn out 1,000 copies for what the comic book partners considered a reasonable price. Three months and $310 later, Flash Theatre went to press.

Each contributed 20 pages. Hoskin turned out various adventures of Captain Toad, a character he'd developed for an animated film that was never made. Roberts blew up frames from American Visual, a live-action film that had been improvised around their studios one Sunday last May [1970].

Dialogue was lifted from The End of the World, a fundamentalist tract that had been left at their door, and the resulting story was renamed Jack d'Repo.

Their approach to their comic was almost completely non-commercial. "We printed it. Then we had no idea what to do after that," Hoskin says.

They went around to some shops, put a few in the mail, tried street selling at the University of B.C. and took out ads in the Georgia Straight. Sales were slow and copies of the first issue are still available.

Issue Two, due out in early summer, is expected to move faster. It will contain the work of at least 10 different hands, Hoskin says, and that should give it a broader appeal.

In the meantime, Oogle Productions, the loose arrangement of studio space that produces Flash Theatre in a former garment factory above a downtown topless club, is taking its initial losses gracefully.

"We just lost complete track of the finances," Hoskin admits with a shrug. "We're not businessmen."

The above is a restored version of a Province feature article by Michael Walsh originally published in 1971. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Is there more to the story of Flash Theatre Presents? Of course. And now that we have Robin Bougie on the job, I’m looking forward to reading about it in some future issue of Gutter Hunter. For more on its editor-publisher, see the introduction to my review of 1988’s Comic Book Confidential. For more on his new magazine, follow the link to The Newest Rant, a St. Louis-based blogger who reviewed Issue #1. Robin Bougie turns 49 today (July 28).