Tuesday, July 11, 1972.

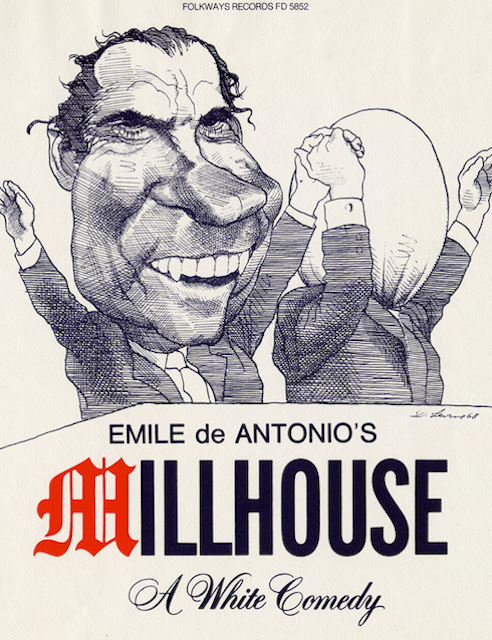

MILLHOUSE: A WHITE COMEDY. Music by L. Bridge. Produced and directed by Emile de Antonio. Running time: 92 minutes. Rated General with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: documentary on U.S. politics.

DOCUMENTARIST EMILE DE ANTONIO may have done Richard Nixon more good than harm with his unashamedly biased biography Millhouse: A White Comedy. The current [1972] U.S. president slips off de Antonio’s spit singed but uncooked, more an object of sympathy than antipathy.

Clearly, this was not the filmmaker’s intention.

Together with a staff of editors and researchers, he has gone over the career of the California-born Republican, with selected incidents and actions designed to destroy Nixon’s carefully-groomed image of honesty and sincerity. His film uses newsreel footage, television kinetoscopes and videotapes, newly filmed interviews, still photos and selected readings from Nixon’s 1962 book, Six Crises, to build his case against the 37th president.

Nixon supporters will easily shrug it off as an insult that proves nothing. Nixon haters will wish that it had been done as well as it should have been.

Millhouse — a play on Nixon’s middle name Milhous — has two particularly expressive moments that show what it is, and how it could have been better. One is its opening image, introduced by a fanfare from the Marine Corps Band. It shows a head being attached to the body of Nixon’s effigy in Tussaud’s famous wax museum.

Despite the London firm’s reputation for perfection, the head is a ghastly likeness, resembling actor Jack Webb more than the American Commander in Chief. Like the wax workers, Millhouse grasps at the image of Nixon, the public face that cries out more for trust and affection than respect.

The second moment occurs when de Antonio’s camera focuses on an attractive middle-aged woman who dated Nixon in his Whittier college days. Though she can remember no personal moments, she does recall Nixon’s campaign for student body president. It was fought, she says, on an issue that the young Quaker had no personal interest in, but that he knew would be a vote-getter.

For an instant, the film provides a glimpse of Nixon the man, a poor boy who should have been his generation’s best expression of the American dream. Instead, he is a political question mark, an opportunist who may one day be looked upon as an American tragedy.

Watching de Antonio’s film chronicle the many contradictions of a political person, I had to wonder what really makes Richard run. He appears to be in pursuit of neither wealth nor great personal power.

Nor does he seem inordinately attached to any ideological program. He lives with killing responsibility, constant personal risk and is vehemently disliked by millions.

Why, then, has he done the reprehensible things he has done to gain and hold office? De Antonio’s film has no answers.

Millhouse: A White Comedy has no more depth than the image-making it attacks. The laughter is hollow because in reality its subject is so chillingly real.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1972. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In the heat of the moment — and, with fears that mob violence will break out across the U.S. today (January 20, 2021), ours is a particularly hot one — it is useful to remember similar times in the recent past. In 2004, for example, documentary filmmaker Michael Moore released Fahrenheit 9/11, his incendiary critique of George W. Bush, on the eve of that year’s presidential election. Though the picture was a financial success, it failed in its mission to bring about Bush’s defeat.

Thirty-three years earlier, social activist Emile de Antonio went after President Richard M. Nixon with his 1971 documentary Millhouse: A White Comedy. Like Bush, Nixon would survive the assault and go on to re-election in 1972. Revisiting the above review, I realize that it was written with the assumption that my daily newspaper readers were familiar with the life and turbulent times of the then-incumbent president. Although personally agreeing with de Antonio’s negative opinion of “Tricky Dicky,” I thought his Punch-and-Judy-Show style of attack unlikely to convince anyone not already opposed to the politician. It’s also worth remembering that the movie had its U.S. premiere some seven months before the Washington Post published its first Watergate break-in report. (For a fine overview of the content and importance of de Antonio’s picture, see historian David Greenberg’s essay on the History News Network’s website.)

Today, an unprecedented 25,000 National Guardsmen are deployed in and around Washington, D.C. to provide security for the inauguration of Democrat Joseph R. Biden as the 46th president of the United States. The moment is historic for a number of reasons, not least for the fact that, at 78, he will be the oldest person to assume the office. To paraphrase a line from John F. Kennedy’s 1961 inaugural address: Let the word go forth . . . that the torch has been kept from a new generation of Americans, clenched in the hands of one who bears much responsibility for the many ills that beset the nation and the world. Just after noon on the East Coast, Biden will deliver an address, expected to be a call for unity in his deeply divided country. Thereafter, if history (and the movies) are any guide, the disappointments will begin anew. Or not. But that unlikely hope is what keeps us tuned into the show.