Saturday, July 2, 1973.

JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR. Co-written by Melvyn Bragg and Tim Rice, based on the rock opera by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice. Music by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Andre Previn. Co-written, produced and directed by Norman Jewison. Running time: 108 minutes. General Entertainment.

GO BACK 18 MONTHS. According to an article in Show magazine, director Norman Jewison is readying a screen version of Jesus Christ Superstar. Feature writer Ralph Blasi describes the project as "courting disaster."

It was a courtship Jewison could have done without. To his credit were a pair of solid box office hits, Fiddler on the Roof (1971) and In the Heat of the Night (1967). In his debit column were the interesting, but financially less successful, Thomas Crown Affair (1967) and Gaily, Gaily (1969). A director more concerned with the value of his own commercial stock would have weighed his chances, found the Superstar project too risky, and slid down the safe side of the roof.

Go back 18 years. On the stage of New York's Mark Hellinger Theatre — the same stage that would one day play host to Superstar — Robert Coote (as Colonel Pickering) is nightly expressing his admiration for Rex Harrison's Henry Higgins. Following the blossoming of Julie Andrews's Cockney flower-girl Eliza Doolittle into the titular My Fair Lady, he enthuses "tonight, old man, you did it!"

For Jewison, the delicate courtship is over. Last night, tonight, and for many more nights to come, he does it. His Superstar is a supercharged, superfine superfilm. A total triumph for the Toronto-born director, it is the year's biggest movie bonanza yet.

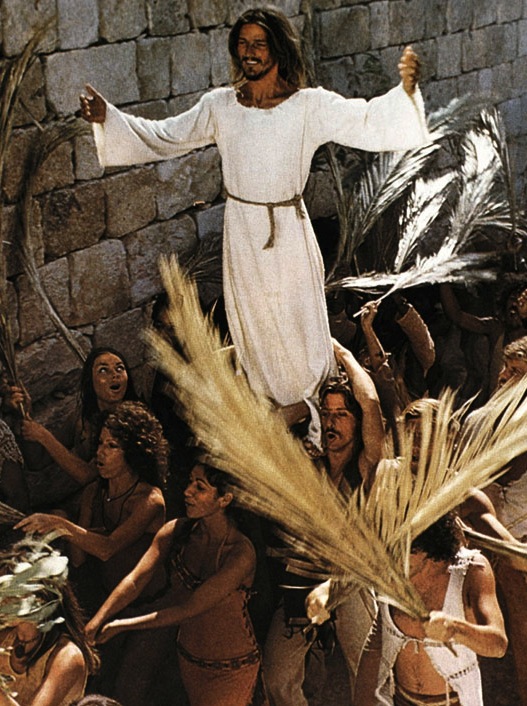

In filming the phenomenally successful rock opera, Jewison gives us a Christ who is alive, sensitive, courageous and solidly human. And, really, it's about time.

It's hard to believe that Jesus Christ, the most influential religious figure in modern history, has been a film star for 77 years. The movies' first recorded life of Christ was ground out in 1897.

Since that moment, practically every screen depiction of the Nazarene has distanced Him into a reverential unreality. A legion of actors, writers and directors have taken their cues from the epicene Jesus of 1912's From the Manger to the Cross, an epic that starred the appropriately named R. Henderson Bland.

Blandness, in one form or another, has been symptomatic of virtually all subsequent Christ vehicles. It has been, that is, until now.

Earlier this year [1973], the screen adaptation of Godspell offered up a joyous, tuneful look at youthful religious ecstasy. Set on the streets of New York, it was a Second Coming and a reiteration in modern musical revue form of the timeless teachings of the Gospels.

Most eagerly awaited, though, was Jesus Christ Superstar. Like You're A Good Man, Charlie Brown, Superstar was originally conceived as a record album. Its success in that format generated the interest that brought it to the stage, and now to the screen.

Created by a pair of young Englishmen, composer Andrew Lloyd Webber and lyricist Tim Rice, it made a dramatic (and necessary) break with orthodoxy. It treats the Christian Gospel not as history, but as myth.

Recognizing the relatively less important role that the various Christian churches have come to play in the day-to-day lives of their nominal adherents, the artists realized that they could assume a new perspective. If the Christ tale now could be ranked alongside the religious myths of the Greeks, the Romans and the Norse, then it could be shaped, interpreted and contemporized. In a word, made art.

Judas, damned for 2,000 years as the betrayer, could be rehabilitated, re-examined and, perhaps, made the representative of all our own modern fears, resentments, hang-ups and harrassments. Jesus, represented for 2,000 year as the spiritual ideal of the world, the Son of God and the King of Kings, now is viewed as a man who is as much a creature of circumstance as its master.

Most dramatic renderings of the Gospel have followed the chronology (and rather petulant tone) of the evangelist Matthew. Superstar, by contrast, picks up on John, focusing on its central question of and enduring fascination with the divinity of the Galilean.

It is this question that everyone in Superstar wrestles with in one form or another. It was this aspect of the album that made it a surprise hit among thinking Christians, and was lost in the lavish Broadway stage production.

Directed by Tom O'Horgan, that production was a surreal pastiche of effects that detracted from the opera's natural power and strength. Said Time Magazine in a cover story on the New York premiere, "Superstar's vulgarity is less in the realm of religion than of theatrical taste."

Filmmaker Jewison knew nothing of the planned Broadway show when, on the Yugoslavian set of Fiddler on the Roof, he first heard the Superstar album. He had his own vision, a particularly cinematic idea of what the show should look like on the screen.

Using the best of the various stage actors — Tom Neely as a cool but still impassioned Jesus; Carl Anderson as the soul-pained Judas; Yvonne Elliman as an open-hearted Mary Magdalene — Jewison saw his film as an entirely exterior drama. He used the natural ruins and desert wastes of modern Israel as his set.

Visually, the film is entirely his. The score, conducted by Andre Previn, is enhanced by a camera rhythm that never fails to feel the music and always manages to make the most of the lyrics.

Recorded in stereo, the theatre sound is magnificent, clearly bringing every word and intonation to the audience. (The newly pressed soundtrack, on the MCA label, makes the score an experience to take home and run over and over again.)

Jewison has indeed done it. Jesus Christ Superstar stands among the best movie musicals ever made.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1973. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Jesus Christ Superstar played first-run in Vancouver for more than a year. It was a movie that offered new delights on every viewing, and we saw it over and over again, going back at least once a month. in 1975, during a working visit to Universal Studios, I mentioned to one of the press relations officers that I hoped to someday buy a 16mm print of the film so that I could see it at home. "You may want to hold off on that," he said. "We have this new thing that we're working on . . ." Three years later, Universal's parent company MCA introduced DiscoVision, a 12-inch silver platter that utilized the first of the LaserDisc technologies. (Superstar was among its first releases and, yes, we did buy a copy.) As it turned out, DiscoVision was among the casualties in the home-video format wars, and for a time VHS videocassettes ruled. Then, in the mid-1990s, the laser technology returned with a vengeance. Reduced in size and cost, the DVD was irresistible. And the high-tech miracles just keep coming. Today, huge flat-screen TVs are affordable, making it possible to celebrate a great movie like Superstar on any arbitrary date that we like.

See also: In May 1974, actor Carl Anderson sat down for an interview with me in Vancouver.