Wednesday, December 28, 1994.

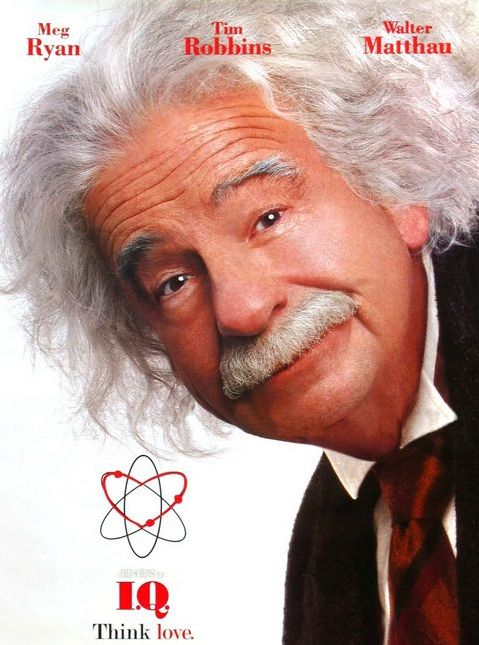

I.Q. Written by Andy Breckman and Michael Leeson. Music by Jerry Goldsmith. Produced and directed by Fred Schepisi. Running time: 95 minutes. Rated Mature with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: Occasional suggestive language.

ALBERT EINSTEIN WAS NO dummy.

In the afterglow of America’s Second World War victory, the famous physicist warned us that “the unleashed power of the atom has changed everything save our modes of thinking, and we thus drift toward unparalleled catastrophes.”

The very model of a modern Jeremiah, the German-born theoretician is remembered as a man of conscience, of science and of traditional religious values. “Gott wurfelt nicht — God does not play dice with the world.”

Fred Schepisi is a quick study. Last year [1993], he achieved limited mass-market success with his finely-crafted screen adaptation of John Guare’s intellectually challenging contemporary drama, Six Degrees of Separation.

Hearing the people’s message, the Australian-born director has lightened up and dumbed down. I.Q., his calorie-free Christmas comedy, offers us Einstein as deutsch uncle gleefully positing a new theory of romantic relativity: “Don’t let your brain interfere with your heart.”

Set in a blessedly simple Happy Days version of 1955, I.Q. is about a great guy — Princeton, New Jersey garage mechanic Ed Walters (Tim Robbins) — and a pretty girl — graduate mathematician Catherine Boyd (Meg Ryan).

It’s love at first sight. But, when the otherwise brilliant young woman fails to recognize it, wise old uncle Albert (Walter Matthau) steps in to play matchmaker.

Winsome as a kitten with a ball of yarn, Schepisi’s picture is a warm hug surrounding us with its period comfort and traditional movie joy. “Don't let your brain interfere . . .”

As written by Andy Breckman and Michael Leeson, I.Q. is a 1940s kind of comedy. The only thing that stands between the young lovers and happily ever after is Catherine’s snobbishness and her lack of self-assurance.

Engaged to a twit — experimental psychologist James Moreland (Stephen Fry) — she’s too properly upscale to really get to know a sterling fellow like Ed. To bridge the gulf, Uncle Al contrives to pass off the grease monkey as a rocket scientist.

A likeable fantasy, it works well enough. Full of sweet reassurance, it’s wonderfully cloying Cold War nostalgia for all those America First neo-conservatives who went to bed on Christmas Eve with images of orphanages, prison walls and multibillion-dollar military build-ups dancing in their heads.

Oops! Where’d that come from?

Pleasant and funny, I.Q.’s designer innocence isn’t in the least malicious. You have to love Ed, whose instinctive, heartfelt American know-how is clearly superior to the cold intellectualism of James, the overeducated foreigner with the Oxbridge accent.

There is a cleverness and even patriotic fervour in the plot twists. It even works in a visit from President Eisenhower (Keene Curtis), the last Republican to occupy the White House who wasn’t a crook, an incompetent, a dissembler or an unappealing opportunist.

Excuse me. I really have no idea where that came from.

Schepisi works hard to offer diversion from present tense realities, creating a rosy memory of a world unblemished by non-white faces.

Grumpy old man Walter Matthau’s Einstein is a comic impersonation of wit and skill. A Hollywood heart film, it’s best viewed with the brain in neutral.

Think about it at all, and you may find fault with its déja view. Think about it too much, and I.Q. becomes a guilty pleasure.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1994. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: I.Q. opened in theatres on Chistmas Day, six weeks after the rancorous 1994 mid-term election in which the incumbent Democratic President Bill Clinton saw both the House and Senate lost to the Republicans, who’d campaigned on something called a “Contract with America.” I’d found the results disappointing, and peevishly allowed my own progressive political leanings to peek through in the above review. As media genius Marshall McLuhan often said, the popular culture reflects and promotes the attitudes, beliefs, and values of our technological society. As a critic, I saw my job as identifying places in which reel life intersected with reality. Because I wrote for a newspaper editorially disposed to corporate values, keeping that job depended on my cloaking my dissent in humour.

Over the years, many celebrities have felt the need to publicly express their own political convictions. Although I.Q. star Walter Matthau kept his party preferences to himself, both Meg Ryan and Tim Robbins were openly Democrats. Robbins, who supported Bernie Sanders over Hilliary Clinton during the primary process, made his directorial debut with the political mockumenetary Bob Roberts (1992), the story of a right-wing folk singer who trades on his celebrity in a run for the U.S. Senate.

In the above review, I called I.Q. “a 1940s kind of comedy.” It certainly maintained the reverence for the U.S. presidency that was a movie tradition until the mid-1960s. The attitudinal shift began with such films as Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 satire Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (in which Peter Sellers played the risibly weak President Merkin Muffley) and the A.I.P. drive-in feature Wild in the Streets (1968), in which Christopher Jones starred as a teen idol whose presidency turns teen rebellion into the law of the land. Bad presidents became a film staple as the Watergate investigations brought Richard Nixon’s administration into disrepute. Though 1976’s All the President’s Men won all the Oscars, it was The Werewolf of Washington (1973) that bit most deeply into the era’s issues. In the run up to today’s election, comedians and commentators alike have been merciless in their criticism of both candidates. Expect the vitriol to continue regardless of who’s sworn in on January 20, 2017.