Wednesday, June 1, 1994.

ARTHUR HONEGGER - MARIUS CONSTANT: Napoléon - Abel Gance (1994; Erato Disques)

AN EAGLE TAKES FLIGHT . . .

Seeking a visual equivalent for the glory that was Napoléon, pioneer filmmaker Abel Gance focused his camera on the eagle. Inspired and incredibly inventive, the French writer-director spent a fortune, and five hours of screen time, to tell his tale.

Because world cinema was still silent, Gance called upon modernist Swiss composer Arthur Honegger to compose and conduct a suitable score for his epic's April 1927 premiere at the Paris Opera House. By all accounts, the event was a triumph, the debut of a motion picture landmark.

For more than 40 years, though, Napoléon was a "lost" masterpiece. Then, in the late 1960s, British film historian Kevin Brownlow made reconstruction of the Gance masterpiece his own life's work.

The eagle took flight again in 1979. Seeing Brownlow's historic restoration became the movie event of the early 1980s. It opened in London and New York with a live orchestra, then toured to such centres as Vancouver (playing the Queen Elizabeth Theatre in July, 1982).

In Britain, the musicians performed a rich, fastidiously period score by Carl Davis. A soundtrack recording was issued on a Chrysalis LP (later CD) in 1983, with Davis conducting London's Wren Orchestra.

In North America, Napoléon was "presented" by Francis Ford Coppola, and was accompanied by Carmine Coppola's cartoon-like score. Issued in 1981 as a Sony Music LP (later CD), its soundtrack features the composer conducting the Milan Philharmonic.

And now there are three. Working with the surviving 20 minutes of Honegger's score, Marius Constant has re-imagined Napoléon's original music, recording the result with the Monte Carlo Philharmonic Orchestra.

Constant, a Romanian-born avant-gardiste, is popularly known as the composer of the 27-second Twilight Zone theme, television's most famous musical signature tune. A student of Honegger's in 1940s Paris, he adopted a more traditional approach to this significantly longer work.

Their collaboration across the years soars like the Napoléonic eagle. To fill in some of the musical gaps, Constant used appropriate adaptations from Honegger's other epic concert works (among them Phaedre and The Tempest).

Otherwise, he drew upon his own sense of the man and his style to create his own original interpretations. Like Davis, Constant is in tune with director Gance's concept of the cinema as "visual orchestra" in presenting the larger-than-life figure of Napoléon to the public.

Unlike Davis (whose score remains true to the music of Napoléon's own 18th century), Constant is true to Honegger, who applied the then-radical musical forms of early 20th-century Europe to the exciting new medium that was cinema.

Indeed, record shops are as likely to stock this digitally-recorded Erato CD among the classical composers as among the soundtracks. In either section, the Honegger/Constant Napoléon is a find.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1994. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

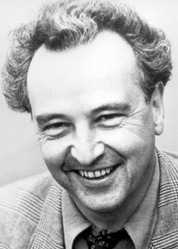

Afterword: One of 20th century Europe’s musical celebrities, Arthur Honegger can be said to have led two lives. Serious music scholars remember him as a member of Les Six, an influential group of Montparnasse-based composers determined to take their art in new, “anti-romantic” directions in the post-First World War era. Working alongside visual artists such as Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso and Coco Chanel, he was a prolific contributor to the modernest movement, creating music for operas and ballets as well as choral and orchestral concerts. His critical breaktrough came in 1921 with the performance of his “dramatic psalm” Le Roi David (King David).

Honegger’s second life began in 1923, when the innovative French filmmaker Abel Gance hired him to score his big screen drama La Roue (The Wheel). Gance would call upon Honegger again for Napoléon (1927), and for his 1931 sci-fi feature La fin du monde (The End of the World). Cinema historians know Honegger for his film music, a composer with some 36 feature film credits, including Raymond Bernard’s 1931 Les misérables, the sound era’s first feature adaption of the Victor Hugo novel. Among Honegger's titles are three English-language features: Hollywood director Anatole Litvak’s First World War drama The Woman I Love (1937); Anthony Asquith’s adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (1938); and Andrew Marton’s 1952 thriller Storm Over Tibet, for which composer Leith Stevens recycled (with credit) Honegger’s score from 1935’s Der Dämon des Himalaya.

In 1954, in a nice squaring of the circle, Italian director Roberto Rossellini directed his wife Ingrid Bergman in the musical feature Giovanna d’Arco al rogo (Joan of Arc at the Stake). Based on Honegger’s ground-breaking 1935 oratorio Jeanne d’Arc au bûcher, the movie brought together the composer’s two careers. Arthur Honneger died in 1955 at the age of 63.