Saturday, October 20, 1985.

COLONEL REDL. Co-written by Péter Dobai. Music after Schumann, Chopin, Liszt, Penn and Strauss. Co-written and directed by István Szabó. Running time: 140 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: some nudity and suggestive scenes. In German with English subtitles.

ISTVÁN SZABÓ THINKS BIG. His feature films constitute “the autobiography of a generation,” the 47-year-old Hungarian director says.

Szabó became an international figure in 1982, the year that his brilliant backstage drama Mephisto beat out Polish director Andrzej Wajda's favoured Man of Iron for the best foreign-language picture Academy Award. The story of an actor whose ability to tack with the prevailing political winds made him a favourite with the leaders of Germany's Third Reich, it explored issues of identity and duty within the context of a tense, personal tragedy.

Szabó's richly deserved Oscar win put him in a position to indulge his passion for grand themes. The result is Colonel Redl, an undisciplined load of nonsense that has already won a selection of film festival awards, including this year's Cannes Jury Prize.

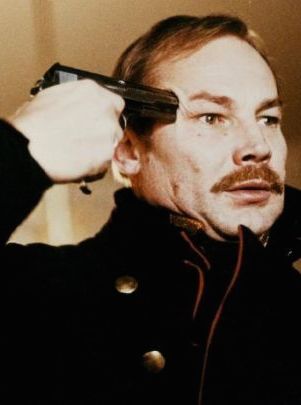

As in Mephisto, Szabó draws his inspiration from historical sources. This time his subject is Alfred Redl, a general-staff officer who served in the Emperor Franz Josef’s Austro-Hungarian army and died by his own hand under mysterious circumstances in Vienna on May 25, 1913.

As in Mephisto, the title role is played by the talented Austrian-born actor Klaus Maria Brandauer. Unlike Mephisto, Col. Redl is less a classically flawed tragic hero than a tiresomely inconsistent dimwit.

The son of a Galacian railway employee, young Redl (Gabor Svidrony) wins a leg up on the social ladder when he is sent as a cadet to the Empire's elite military academy. A fortuitous, largely accidental friendship with young Baron Kristof Kubinyi (György Rácz) gives him a taste of aristocratic society, and he internalizes a sense of service to his betters.

Or at least that's what appears to happen. When we meet the adult Redl (Brandauer), he is initially presented as a capable officer on his way up through his own military merits.

His old buddy Kubinyi (Jan Niklas) has a hot-blooded sister, Katalin (Gudrun Landgrebe), who thinks enough of Redl to seduce him and become his mistress.

Having been so well educated as to how the system works, and having been granted such generous access to its benefits, Redl inexplicably transforms himself into a charmless martinet and first-class sneak. His information-gathering abilities are eventually recognized at headquarters, and he is recalled to the capital, where he is put in charge of the Evidenzburo — the intelligence unit responsible for internal security.

Szabó regards Redl's story as deeply significant. The Central European writer/director would have us believe that the shot that ended the life of Archduke Franz Ferdinand (Armin Mueller-Stahl) at Sarajevo (and, incidentally, started the First World War), was a direct echo of the shot that felled Redl.

I might have taken the idea a little more seriously if Szabó had managed to bring either Redl or his world to life. Too bad that his film, tinted a deathly blue throughout, is more interested in odd, often distracting stylistic trickery than coherent narrative.

Under Szabó’s antic direction, Brandauer's Redl seems driven by unseen and occasionally contradictory demons. The film fails because its auteur is unwilling (perhaps unable) to show who or what those demons are.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1985. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: It’s complicated, this business of art and life. Born in 1938, István Szabó was the son of Jews who converted to Roman Catholicism, but who nonetheless were persecuted by Hungary’s native Nazis during the Central European nation’s Second World War alliance with Germany. A decade later, in the post-war Hungarian People’s Republic, Szabó was a student at Budapest’s Academy of Theatrical and Cinematic Arts. Having survived one war, he knew how to keep his head down and his options open during the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, an uprising suppressed with the help of a Soviet military invasion. He made his feature film directorial debut in 1964 with a romantic drama called Age of Illusions.

In 2006, a newspaper in Hungary’s post-Soviet Third Republic revealed that Szabó had kept his place in the prestigious school by cooperating with the State Protection Authority, a.k.a. the secret police. Between 1957 and 1961, he is said to have submitted 48 reports on 72 people, an experience that must have had considerable influence on his worldview.

Bizalom (Confidence; 1980), his sixth theatrical feature and the first to reach Vancouver, was the story of a couple in hiding in Budapest during the Nazi years. An Academy Award nominee in the Best Foreign Language Film category, it established Szabó’s international reputation. A year later, he’d win that Oscar for Mephisto. In the above review I described his 1981 picture as “the story of an actor whose ability to tack with the prevailing political winds made him a favourite with the leaders of Germany's Third Reich, (a film that) explored issues of identity and duty within the context of a tense, personal tragedy.”

Colonel Redl was, according to New York Times critic Richard Grenier, an “oddity.” Writing in 1985, Grenier marvelled that “Mr. Szabó has undertaken to portray the colonel sympathetically, a job that, historically speaking, takes some doing.'' In recent years, critics have come to regard Szabó’s sympathy for historic devils as more personal than we’ve come to expect in commercial cinema. And, in the complex mix of politics and commerce that is the stuff of popular culture, his story is just one among many yet to be told.