Friday, October 14, 1994.

PULP FICTION. Music co-ordinated by Mary Ramos. Written and directed by Quentin Tarantino. Running time: 154 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning "some violence, frequent very coarse language."

ACTORS GOTTA LOVE HIS ASS. Not literally, of course, but in the respectful sort of way that Ronald Reagan regarded Oliver North for the many favours that the former marine colonel did for the beloved U.S. president during his term of office.

Actors, among them John Travolta, Bruce Willis, Uma Thurman, Harvey Keitel and Samuel L. Jackson, love the respect they get from Quentin Tarantino, and it shows.

As a writer, Tarantino wins them over with huge, showy scenes full of close-ups and fine, chewy, character-building dialogue that focuses attention on them, the quality of their performances and their ability to hold an audience with the most basic elements of their craft — words, words, words . . . .

As a director, he casts them in ambitious, ingeniously outrageous ensemble pieces like Pulp Fiction, a film that is retro and neo, in your face and out of sight, all at the same time. I'd call him the Gen-X Robert Altman if I didn't know how much people currently between the ages of 13 and 35 loathe that term.

There is an Altmanesque Short Cuts vigour in the way Tarantino weaves together 3½ stories — all of them set in a stylized Los Angeles underworld — in which the lives of a dozen major characters intersect in various, occasionally violent, situations.

Like a playful graduate student, Tarantino violates the established grammar of his medium to achieve dynamic theatrical effects. Actors have to love the way he stays in the moment past the time of the expected cutaway, stays with their characters, moving past action into being.

Pulp Fiction is a movie that starts in the middle of its story, flashes back to the beginning, plays through to the end and then returns to the middle for its conclusion. Along the way, it reinvents the gangster movie by making a marriage between two distinct crime film traditions.

Tarantino recognizes the Runyonesque tradition of cute, comically humanized mobsters in which the violence is all off stage and there is lots of talk and even romantic comedy plotting. (Remember Sylvester Stallone in 1991's Oscar?)

Is it possible to fuse that with the ultraviolence of hard-edged social tragedy? To combine it with the sort of picture in which strong, silent men suppress their humanity and become killing machines whose first loyalty is to their crime family?

It is. The satirical edge that Oliver Stone claimed for his nauseating Natural Born Killers (1994), Tarantino achieves.

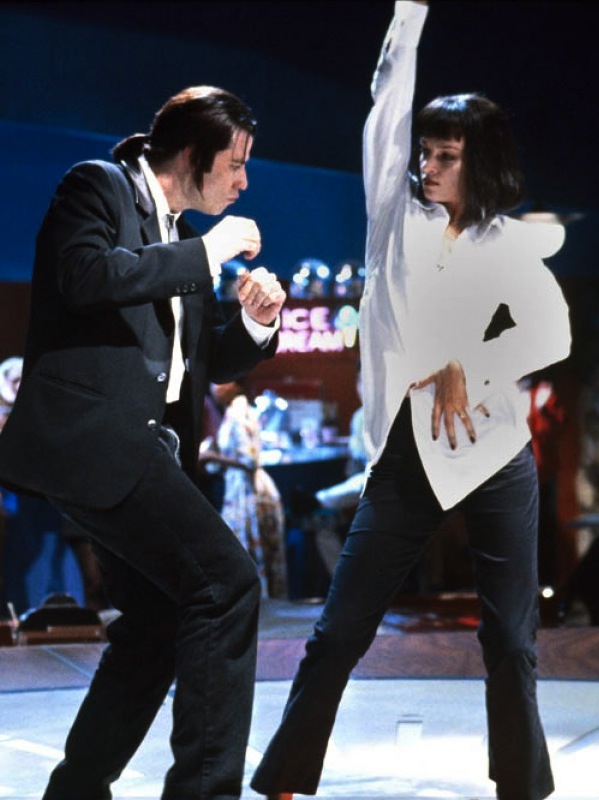

Travolta, for example, plays a monster named Vincent Vega. His character smokes, drinks, does all the heavy drugs and kills without remorse. Given the opportunity, he also dances up a storm, which in context makes perfect sense.

Tarantino's genius is getting all of his contexts down pat. His special skill is in engaging a corps of talented name performers in the enterprise of bringing such monsters to life. Like the best pulp fiction writers, they've created something fascinatingly vile and utterly irresistible.

* * *

SHOW BUSINESS BIBLE — Among Pulp Fiction's highlights is Jules Winnfield, the scripture-quoting hit man played by Samuel L. Jackson, who cites "Ezekiel 25:17" as the source of his most mesmerizing speech."The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the inequities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men," he tells his intended victims. "Blessed is he who in the name of charity and good will shepherds the weak through the valley of darkness, for he is truly his brother's keeper and the finder of lost children.

"And I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious anger those who attempt to poison and destroy My brothers. And you will know My name is the Lord when I lay My vengeance upon thee."

Don't bother looking it up. Much milder than the actual Book of Ezekiel (which is filled with mind-numbing rants, denunciations and condemnations with nary a good shepherd in sight), it is a screenwriter's cut-and-paste job, the Gospel according to Tarantino.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1994. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Often included among the "video-store generation" of directors is Kevin Smith, whose resume includes a semester at the Vancouver Film School and work in a New Jersey convenience store. Released the same year as Pulp Fiction, Smith's first feature, Clerks, drew upon that experience, and introduced audiences to his Silent Bob character. Arguably a more interesting and original auteur than Tarantino, Smith has remained an independent filmmaker, producing low-budget features. Tarantino has succeeded with a series of pictures revisiting the violence-prone genres of his youth. He followed the noir-inspired Pulp Fiction with 1997's Jackie Brown, recalling the blaxploitation pictures of the 1970s, and paying special tribute to actress Pam Grier, cast in the title role. His Kill Bill (2003, 2004) double feature was a feminist-friendly take on martial arts movies, while Death Proof, Tarantino's contribution to 2007's Grindhouse project, drew upon the conventions of psycho killer movies. Inglorious Basterds (2009) mocked comic-book war movies. Django Unchained (2012) was a racially-charged riff on the spaghetti western. In November, he plans to release The Hateful Eight, another western, this time an homage to the television westerns of the 1960s.