Wednesday, March 11, 1992.

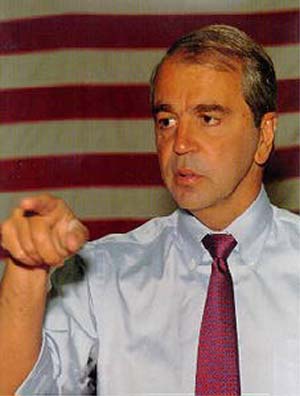

I LIKE PAUL TSONGAS.

A politician who trades in issues rather than image, the U.S. presidential hopeful comes across as a thinking man’s candidate. “I’m not perfect,” he told rival Bill Clinton in a recent [1992] television debate, “but I’m honest.”

I believed him. After all, the Democrat some commentators call “Saint Paul” and I have two important things in common.

One is our inescapable personal charisma.

The other is cancer survival.

Until last week, I believed in him.

Then, suddenly, Saint Paul’s halo slipped.

On the defensive over his own health care proposals, Mr. Intellectual Honesty took a gratuitous swipe at the guys who saved my life.

“As wonderful as the Canadian system is,” he told an Atlanta audience on the eve of the Georgia primary election, “if I had been in Canada when I got cancer I might not be here today."

American understanding of “the Canadian system” is often less than perfect. Why did the former Massachusetts senator believe he was better off in Boston than, say, Vancouver?

“Because,” he said in a follow-up interview, “the research that was being done, very experimental, was here. And if it hadn’t been for that, I would have been given normal cancer treatment, survived for a couple of years and be in the ground today.”

American belief in the natural superiority of all things American is quite breathtaking. Even so, I’d expected better of the witty, self-effacing senator. Instead, his remarks display both arrogance and ignorance.

Tsongas’s resume notes that he resigned his U.S. Senate seat in 1984, after the discovery of his non-Hodgkins lymphoma. In 1986, he became one of the first 50 Americans to undergo an expensive new type of bone marrow transplant.

His resume does not mention that the discoveries that led to this life-saving technique were made 30 years ago by research scientists working at Toronto’s Princess Margaret Hospital.

World-class cancer research is also done in Vancouver. I became aware of this in 1977 when I was diagnosed with an embryonal cell carcinoma. To paraphrase the senator, if I had been in the U.S., I probably wouldn’t be here today.

I base that belief on the fact that the onset of the disease was virtually painless. Had I been an American with no health coverage, I certainly would not have incurred the expense of a doctor’s visit for an apparently minor annoyance.

As it turned out, my “annoyance” was of the killer kind. Within days of my diagnosis, I was in the operating theatre. A few weeks later, I was back on the table for a second session, one in which a surgical team pursued the spread of the disease for more than six hours.

(Incidentally, Senator, one of my closest personal friends at that time was a Seattle-based physician who assured me that I was being treated in one of the three finest facilities in North America. He also mentioned that getting the same kind of care in either of the two U.S. locations would have cost me my house.)

Chemotherapy followed and, yes, the Cancer Control Agency of B.C. uses state-of-the-art experimental drugs. Some of the most advanced work in the world is done here, and I didn’t have to be a member of a millionaires’ club to benefit from it.

Senator Tsongas likes to say that he’s “living proof” that his country has quality health care. Well, I’m living proof that we go them one better.

Saturday evening [March 7, 1992], in an address to the Vancouver Institute, B.C. appeals court Justice Peter Seaton put his finger on the real difference between us.

“I’ll accept that (American) presidents and senators get better health care than the average Canadian,” said Seaton, chairman of the recent provincial royal commission on health care and costs.

“They probably get better care than the average American, too,” he said. “Especially the 30 million with no insurance at all.”

The above is a restored version of a Province op-ed commentary by Michael Walsh originally published in 1992. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In 1992, when the U.S. population was 256.5 million, Justice Seaton noted that 30 million had no medical insurance. In 2017, seven years after the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”), the population is estimated to be 322.8 million. According the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of uninsured currently stands at 29 million. An imperfect legislative solution, it has been under attack since its passage, with its repeal and replacement a core promise of candidate Donald Trump and his Republican Party. To date, they haven’t been able to get their act together, suffering a major embarrassment last week (March 24) when party factions failed to agree on a bill designed to do just that. For the last half century, American politicians have represented the interests of private insurance companies, for-profit hospitals and multinational pharmaceutical corporations above those of the nation’s citizens. To quote one of President Trump’s favourite Tweet words: Sad.

Paul Tsongas withdrew from the 1992 presidential race after the Super Tuesday primaries confirmed Bill Clinton as the Democrats' preferred candidate. A few years after Clinton entered the White House, Tsongas suffered a recurrence of his cancer. He died in January, 1997.