Monday, February 1, 1988

WALKER. Written by Rudy Wurlitzer. Music by Joe Strummer. Directed by Alex Cox. Running time: 94 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: frequent gory violence.

RONALD REAGAN FAVOURS AID to the Nicaraguan contras. In public speeches, he calls them "freedom fighters." At least once, the President has compared these U.S.-backed mercenaries to America's "Founding Fathers.'' They are his surrogates, waging a guerrilla war against the elected government of Nicaragua.

Alex Cox dislikes the contras. He prefers to compare them to Los Immortales, the privateers who followed William Walker to Central America in 1855.

Cox, the British-born director of the cult hits Repo Man (1984) and Sid and Nancy (1986) takes exception to the current American administration's interventionist approach to foreign relations. An angry young man, he sees in the story of Walker's U.S.-funded "liberation" of Nicaragua a profound lesson for today.

Never heard of Walker, you say? According to contemporary reports, William Walker was the most popular person in pre-Civil War America, a "grey-eyed man of destiny."

Something of a Renaissance man, the Nashville-born adventurer held degrees in both law and medicine. A charismatic figure, he was a firm believer in "Manifest Destiny" or, in Walker's own words, "the God-given right of America to dominate the Western Hemisphere."

He backed up his words with deeds, leading an independent invasion of Mexico in 1853, and an armed assault on Nicaragua two years later.

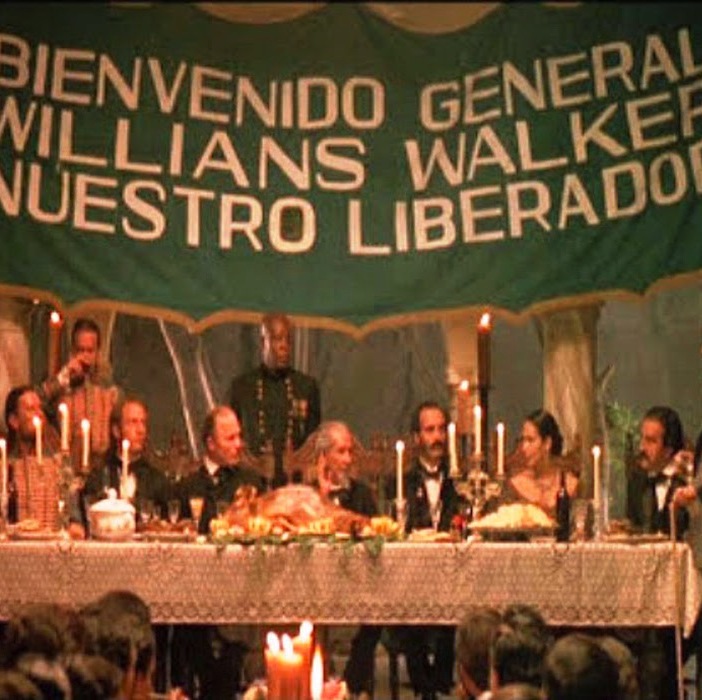

Capturing that nation's capital, Walker took control of its government and, eventually, proclaimed himself president. In a bid for Southern American support, he legalized slavery in his republic.

Americans should remember Walker, Cox insists. Based on his "true story," his film is a combination of history lesson and moral fantasy with violent shock effects and punk humour.

As written by Rudy (Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid) Wurlitzer, it is a period epic full of meaningful anachronisms — Coke bottles, contemporary newsmagazines, a helicopter — dropped into the narrative to underscore the modern parallels. Indeed, actor Ed Harris's severe, steely-eyed Walker turns out to be the only character portrayed as an authentically 19th-century figure.

Stylistically, Cox's picture is a cross between Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch (1969) and Richard Lester's How I Won the War (1967), a throwback to the kind of crazed, committed filmmaking popular in the late 1960s.

Though I can't help admiring its passion and rich referential detail, I left the theatre disappointed. Despite its dedication to truth and justice, I was annoyed by Walker's lack of subtlety, and its somewhat smug self-righteousness.

Here is a timely, relevant tale that desperately needs telling. Here, unfortunately, is a cinematic approach that may well confine Walker to audiences of film cultists and the politically like-minded.

Given the historic importance of events unfolding in Central America, Cox's picture could have been truly important. Instead, it settles for being notorious.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1988. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: As we await the media reaction to Alex Cox's adaptation of Bill, the Galactic Hero, I can't help but notice how well Walker, his 1987 assessment of U.S. foreign policy, is summarized by student skeptic River Tam in the opening scene of Joss Whedon's Serenity (2005). "We meddle." River has just heard her teacher justify the Alliance's war on "the savage outer planets," and the girl is having none of it. "People don't like to be meddled with. We tell them what to do, what to think. Don't run. Don't walk. We're in their homes and in their heads, and we haven't the right. We're meddlesome." As it was in the mid-1980s, so it is today.

Historic spoiler alert: Though recognized by the U.S., William Walker's Nicaraguan republic was opposed by a coalition of Central American nations that included Costa Rica, Honduras and El Salvador. Defeated, Walker was repatriated to the U.S. in 1857. Ever the adventurer, he took on another nation-building assignment in Honduras in 1860. Captured by an unsympathetic British Royal Navy commander, Walker was delivered into the hands of the Honduran authorities, who summarily executed him.