Friday, May 21, 1976

ALAN J. PAKULA IS A man wary of happy endings. Although he has directed five films since 1969, only one, his most recent, comes close to what one might call an upbeat conclusion.That film is All the President's Men, the story of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, the Washington Post reporters who collected a Pulitzer Prize for their Watergate coverage. "I would never have believed it as a film if it were not based on truth," Pakula, 48, told me during an [1976] interview in Seattle.

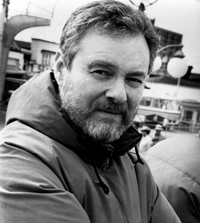

Pakula, sporting a Commander Whitehead beard, blazer and grey flannels, was a last-minute addition to the line-up of guest speakers assembled for the Ninth Motion Picture Seminar of the Northwest. The two-day professional film-makers' conference attracted nearly 700 persons to the Seattle Centre Playhouse.

Describing All the President's Men as "a how-to film," Pakula told his Seattle audience that he had been most concerned "with visually representing the obsession of investigative reporting." Offering what he called "my own tacky Freudian interpretation," he suggested that "a Catcher-in-the-Rye syndrome moves investigators to constantly expose untruths and the hypocrisies of people in power."

A Yale graduate in drama, Pakula got his start in Hollywood as a production assistant. In 1955, he became a full-fledged producer and in 1969 he directed his first feature, Liza Minnelli's dramatic debut, The Sterile Cuckoo.

His second film, 1971's Klute, starred Jane Fonda. Under Pakula's direction Fonda turned in an Oscar-winning performance. His more recent projects, 1973's Love and Pain and the Whole Damn Thing, and 1974's The Parallax View, were less well received.

Then came the assignment to direct All the President's Men, a property that actor Robert Redford had husbanded from its first draft as a book. According to Pakula, he said to Redford, "Let's be damn sure about the kind of film we want to make."

Ruled out was the idea of "an historical montage." Both the actor and the director agreed that "Butch Woodward and the Sundance Bernstein" was also out. Initially, Redford had considered shooting the film in black and white, to give it a "documentary look."

Pakula objected. "Reality gives you wonderful, wonderful gifts," he said. On visiting the Washington Post newsroom, he discovered "a relentlessly fluorescent-lit room," done up in "poster colours."

The effect, Pakula said, was of "a harsh white world without shadows, a world where nothing could be hidden." The irony was fascinating.

"Most detective stories take place in seedy environments," he said. By contrast, the Washington suburbs were a world "of well-kept lawns. where the sun always shines and people pay their taxes on time."

By going "back to a crisp, hard style," Pakula said he was attempting to "represent the reporters’ style and perceptions." Later, in our interview, the director admitted that his film was not an altogether factual recreation.

A fictional character, Sally Aiken, was added to the story when Marilyn Berger, the real-life reporter involved in certain incidents described in the book, refused to allow her name to be used in the movie. A confrontation scene was invented, Pakula said, "to get Dustin (Hoffman) at his most manic." Events were compressed because the director "wanted pace," and fidelity to the ”tedium" of the job would have "cut the tension."

Pakula answered my questions in a sunlit plaza not far from the Space Needle, the Seattle landmark where the opening scenes of his previous film, The Parallax View, were shot. It, too, focused on investigative reporting. A fictional story, it starred Warren Beatty as a reporter whose quest for the truth ends tragically.

The two films were really "two sides of the same coin," Pakula said. "Each deals with the importance of the individual. If one is pessimistic and the other optimistic it is because I have both pessimism and optimism within me."

In The Parallax View, "I destroyed the American hero myth." Reporter Beatty is smart enough to uncover a deadly conspiracy but ends up its victim. In All the President's Men, with Redford and Hoffman, "I resurrect it at a time when it really is true.

"Those might be opposite attitudes, but the simple answer is they're both part of me," Pakula said. "There's a part of me that thinks we are losing the power to control our lives, and another side that wants to believe that it's not so."

Asked about Woodward and Bernstein's controversial new book — would Alan J. Pakula like to direct The Final Days? — he sidesteps the question.

"I hear that Walter Matthau says he'd like to play Nixon," he non-answers, grinning.

The above is a restored version of a Province interview by Michael Walsh originally published in 1976. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

AFTERWORD: Between 1967 and 1985, the annual Motion Picture Seminar of the Northwest (later The Film and Video Seminar of the Northwest) brought together hundreds of filmmakers, crew, and vendors for a two-plus-day event in Seattle. A regional conference, it featured timely talks and fascinating presentations by a Who's Who of Hollywood professionals. It inspired a generation of local industry builders from Northern California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Alaska, Alberta, Saskatchewan and, of course, British Columbia.