Sunday, March 12, 1995.

COLONEL CHABERT (original title Le colonel Chabert). Co-written by Jean Cosmos and Véronique Lagrange; based on the 1832 novel by Honoré de Balzac. Music conducted by Major Péaud. Co-written and directed by Yves Angelo. Running time: 110 minutes. 14 Years Limited Admission with the B.C. Classifier's warning: "occasional volence and suggestive scenes." In French with English subtitles.

LIKE MARTIN GUERRE, ANTOINE Chabert was thought dead, lost to his wife and country in battle. In 19th-century Paris, as in 16th-century Artigat, life went on.

Then, like the medieval Martin, Colonel Chabert returns to claim what is his. Resurrectees, he discovers, are less welcome in Restoration France than in the days of the ancien regime.

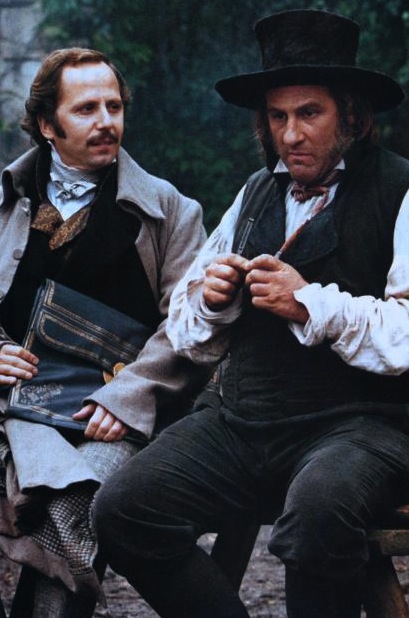

And one more similarity. Like Guerre in Daniel Vigne's 1983 feature La Retour de Martin Guerre, Chabert is played by French acting institution Gérard Depardieu.

The Gallic Marlon Brando, Depardieu is hardly the "scarecrow" French writing institution Honoré de Balzac described in his 1832 novel. No matter; he fills out the role with commanding authority, giving a more disquieting account of a near-death experience than any recent shock thriller.

The year is 1817. A cavalry officer in Napoleon's Grand Army, Chabert officially died on February 8, 1807. He is remembered as a hero of the battle of Eylau, a bloody encounter between French and Russian forces during the period of the Second Coalition.

His wife, the former Rose Chapotel (Fanny Ardant), accepted the Emperor's condolences and claimed her inheritance. Ambitious and financially astute, she is now an aristocrat, the titled wife of Count Ferraud (Andre Dussollier), Louis XVIII's State Counsellor.

Chabert, a spectral figure from another age, is neither convenient nor welcome in the countess's new life. In a brilliantly understated opening montage, first-time director Yves Angelo makes it clear just how dead his title character really is.

In the winter twilight, we are invited to witness the aftermath of battle. As the French dead are stripped and stacked, Angelo shows us the process by which Chabert, gravely wounded and catatonic, ceases to exist.

Body armour is removed from cavalrymen's corpses, representing the laying bare of their hearts. Uniforms are stripped off, depriving men of their rank and identity.

Weapons are collected — officially dead, Chabert has no economic and limited legal means to assert his claim — as are boots. An anonymous body stacked in a mass grave, he even loses his individuality.

Ten years later, the living corpse obtains an interview with the prosperous, ingeniously devious lawyer Derville (Fabrice Luchini). "I can describe death," Chabert says with unaffected assurance.

"It is red . . . then blue. It's cold. Most of all, it's silent. Death is the silence of death."

Intrigued, Derville takes the case. After all, he says, "a lawyer sees such things as a writer could never imagine."

A tale of emotional and moral complexity as well as social intrigue‚ Le colonel Chabert was one of the more than 90 stories in Balzac's La comédie humaine cycle. Angelo's tightly crafted feature brings to life a transitional moment in the emergence of modern France.

Involving despite its cool distance, Colonel Chabert offers an even-handed examination of people whose motives are chillingly contemporary.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1994. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: "Long before twentieth-century discourses on shell shock and post-traumatic stress disorder, Napoleonic veterans like Balzac's Sergeant Falcon [in 1829's Les Chouans] and Colonel Chabert suffered the lingering emotional effects of combat, from the death of friends to the horrors of being buried alive," Brian Joseph Martin wrote in his 2011 book Napoleonic Friendship: Military Fraternity, Intimacy, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-century France. "Confronted with the transition from military to civilian life, these veterans faced the combined ravages of combat trauma, political persecution and social rejection." Canada's Kate MacEachern would probably agree. Her current journey — details are on her The Long Way Home website — stands as a powerful metaphor for how far we've come and how much further we have to go. Balzac, the great-hearted novelist who was born the year Napoleon became First Consul, lived to see Bonaparte's Empire fall, the Bourbon Restoration, the July Monarchy and the rise of the Second Republic. They were times of constant tumult that influenced his outlook and made him an influence on other writers, such as Charles Dickens, Henry James and Émile Zola. The plight of Balzac's Colonel Chabert has been been the subject of several screen adaptations for European TV, and three theatrical features so far. The award-winning French cinematographer Yves Angelo made it his directorial debut. Though little seen in North America, Angelo's subsequent features have maintained a focus on "la comédie humaine" at the heart of Balzac, and the socially progressive writers and filmmakers that he inspired.