Wednesday, January 30, 1985

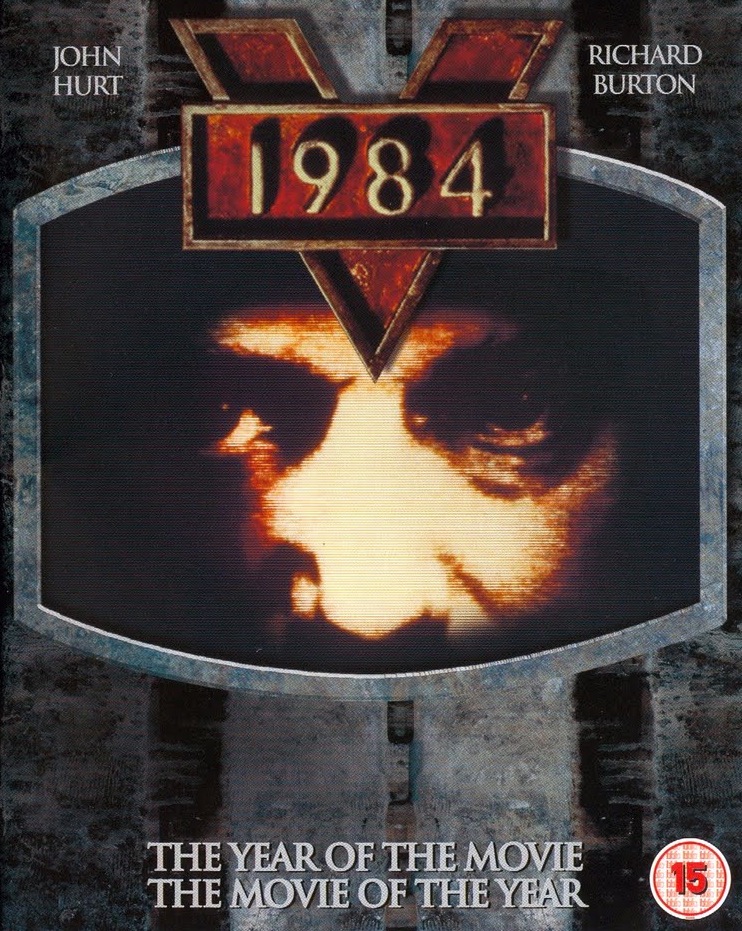

NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR. Based on George Orwell's novel. Music by Dominic Muldowney and The Eurythmics. Written and directed by Michael Radford. Running time: 115 minutes. 14 Years Limited Admittance with the B.C. Classifier's warning: some nudity, occasional violence and suggestive scenes.

"If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face — forever.''

—from Nineteen Eighty-Four (published 1949)

WELL, IT'S OVER. Nineteen eighty-four, the year, is history. It is now possible to appreciate George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four as a work of literature rather than an exercise in political prognostication.

Such was not the case in 1955, the year that the novel was first adapted to the screen. Viewing the project as a Cold War parable, director Michael Anderson's 1984 featured two different endings — a defiantly upbeat one for British audiences, and Orwell's own more pessimistic version for offshore release.

In the style of the mid-1950s, inner-party member O'Brien (renamed O'Connor) was played by lean, suave Michael Redgrave. Burly, intense Edmond O'Brien was cast as outer-party rebel Winston Smith, while blonde, bosomy Jan Sterling filled out the role of his illicit lover Julia.

Last year, Nineteen Eighty-Four went before the cameras for a second time. Adapted and directed by 38-year-old Michael Radford, the new version is not a tired sci-fi drama, but a stunningly powerful tribute to Orwell's dystopic vision, an alternate reality that remains the blackest of all black comedies.

Radford's film catches the chill of Oceania on that "bright cold day in April (when) the clocks were striking thirteen." His film opens with us, the movie patrons of 1985, peering through the looking glass at the audience gathered in a party-approved cinema in the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Here, we can catch sight of the major protagonists. Near the front is big, ominous-looking O'Brien (Richard Burton in his final screen role) wearing the neatly tailored coveralls of an inner-party member.

Further back is Winston Smith (John Hurt), a hungry, haunted little man of 39, who has just been spotted by the much younger Julia (Suzanna Hamiliton), a small-breasted brunette with clear eyes and the face of a wanton child.

The screen they are watching is ablaze with violent images and insistent slogans.

Theirs are the faces of Oceania, the ultimate totalitarian society, where war is the never-ending story and power is its own end.

Smith, a man tortured by dreams of another, better reality, deliberately commits ''thoughtcrime'' to assert his humanity.

In stolen moments with Julia, Smith feels the stirrings of love and becomes guilty of "sexcrime.'' Eventually, the soft-spoken, utterly ruthless O'Brien teaches them that theirs is a world in which the ultimate reality is betrayal.

Radford and his cast take us inside Orwell's nightmare to show us Big Brother's realm, a place where the state maintains a horrific stasis, a permanent present that allows for neither future hope nor past memory,

Here, humanity goes down to defeat.

Shot in London during the very months described in the book, Nineteen Eighty-Four is a film that is not only faithful to its source, but inspired film-making as well. Radford has produced a visionary wonder to stand alongside such classics as Metropolis (1927) and Things to Come (1936).

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1985. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In the mid-1980s, with the memory of heroic Watergate journalism and Richard Nixon's failed presidency still fresh, it was easy to think that we had dodged that Orwellian bullet. The dreaded year came and went and, instead of a scowling Big Brother, the U.S. had as its elected leader a "great communicator," the avuncular Ronald Reagan. Or so it seemed. In November 2011, online essayist Carl Gibson began a posting with the words "George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four wasn't meant to be an instruction manual." He was expressing a growing belief that those in power had found in the novel's mock appendix "The Principles of Newspeak" just that, and were using its thought-limiting directives to create a modern surveillance state. An intensely political person, George Orwell died in 1950, leaving Nineteen Eighty-Four as his last words on the subject. By contrast, the Oxford-educated Michael Radford remains an artist rather than an activist, preferring to make films such as Il Postino (The Postman, 1994) and The Merchant of Venice (2004). Despite his astute channelling of Orwell, none of his subsequent films have been particularly political.