Thursday, October 2, 1980.

ORDINARY PEOPLE. Written by Alvin Sargent. Based on the novel by Judith Guest. Music adapted by Marvin Hamlisch. Directed by Robert Redford. Running time: 123 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: some coarse language and swearing.

LIKE A CAVALRY SCOUT reading sign, hospital emergency room staff can infer much from very little. Take slashed wrists, for instance.

When the cuts run horizontally across the vein, the patient is usually more interested in attention and help than dying. When the cuts are vertical along the vein, the victim is a sincere suicide.

Conrad Jarrett (Timothy Hutton) has three vertical scars on each wrist. An l8-year-old son of the American heartland, his attempted self-destruction is serious.

Conrad's story is told in Ordinary People, a solid, absorbing domestic drama directed by acting superstar Robert Redford. His first as a director, the film leaves no doubt that the 43-year-old performer is not only deadly serious about directing, but genuinely talented as well.

Ordinary People is a slice of life that cuts on the vertical. Incisive and penetrating, it takes a hard, honest look at WASP America.

To appreciate the extent of Redford's achievement, one need only recall the monumental failure of New Yorker Woody Allen's "serious" film Interiors (1978). A slavish homage to Swedish director Ingmar Bergman, the film focused on the emotional disintegration of a well-to-do (and apparently Catholic) New York family.

Writer/director Allen, a specialist in Jewish-American humour, knew not whereof he wrote. Interiors was synthetic, self-indulgent, insulting nonsense. It proved only that a media-approved "genius" could make a fool of himself.

Redford is no fool. For one thing, his setting is exactly right. Ordinary people, the well-to-do white folk who really do believe in God and country, don't live on Long Island. You find them, as the director does, in Chicago's North Shore suburbs, in places with names like Deerfield, Highland Park and Lake Forest.

Redford's film is a report on the current state of the American Dream. It opens with a look at the community, a Norman Rockwellian vision of tree-lined streets, white-painted houses and beatific calm. The sound of a choir is heard as the camera approaches the high school.

Wholesome, athletic Conrad Jarrett makes one think of that line from Summertime: "Your daddy's rich, and your mama's good looking'."

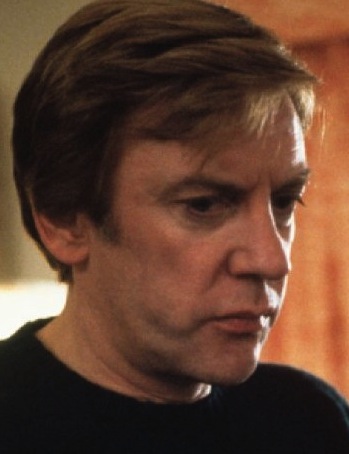

His father, Calvin (Donald Sutherland), is a successful tax lawyer: bland, correct and ultimately caring. Elizabeth Jarrett (Mary Tyler Moore) is an attractive matron, a woman who was probably winsome once, but has now turned inward, her soul tastefully turned out in tan suede.

Conrad sings in the choir. Conrad also sits bolt upright in the middle of the night, his eyes full of terror.

The Jarretts are a family on the ropes emotionally, their tranquillity rocked by two recent tragedies. First, Conrad's older brother Bucky was lost in a boating accident. Then, Conrad, consumed by a combination of resentment and guilt, tried to kill himself.

The film picks up the Jarretts' story some 18 months later. We follow them through the after-shocks as the individual survivors evaluate their lives in the autumnal twilight.

Like Allen in his pseudo-Bergman phase, Redford shows considerable respect for the European style of filmmaking. His images make effective use of spatial relationships, the subtle symbology of set decoration and the mood-enhancing power of light.

The Jarrett home, for example, is preternaturally orderly and always in the best of taste. It looks as if Good Housekeeping magazine photographers are expected at any moment.

The importance of proper interior decorating is obviously lost on Dr. Berger (Judd Hirsch), Conrad's psychotherapist. By contrast to the old homestead, his walk-up office is a utilitarian closet furnished in early Goodwill.

But it's here that Conrad begins to understand himself and his parents. Because his sessions with Berger are scheduled for late afternoon, the scenes in the psychiatrist's office become progressively darker, an accurate representation of the progress of the season, as well as a visual reflection of the boy's descent into the depths of his own being.

Redford's use of such technique is deliberate but unobtrusive. The mood of his film is low key, itself a reflection of screenwriter Alvin Sargent's adaptation of Judith Guests's 1976 novel.

Sargent's script is a masterpiece of understatement. Well-bred ordinary people are not demonstrative, not even during an emotional crisis.

The emotions are there, though, evident in the performances of his key players. Hutton, the son of the late Jim Hutton, brings energy, discipline and a sense of desperation to his role.

Moore, an actress absent from the big screen for at least a decade, offers a tightly controlled portrayal of a tightly controlled woman. Best known as a TV comedy star, Moore matchs her co-stars' dramatic power, creating a character whose true personality is revealed less in her dialogue than in the set of her jaw, or choice of posture.

Sutherland, an actor who often goes off the deep end, here gives a restrained, eloquent, painfully believable performance. He brings to life a good man desperately trying to do the right thing. I'll be surprised if all three names aren't heard again at Oscar time.

Reality is not hard to find in the real world. Walk down any street, knock on any door and you'll find an absorbing true story.

Reality is rare in the picture business. The fact that director Robert Redford found some, and turned it into a moving motion picture, is what makes Ordinary People an extraordinary film.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1980. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: At Oscar time, surprisingly, Donald Sutherland was the one name not heard. While Robert Redford was honoured with the best picture and direction awards, Timothy Hutton with a supporting actor win and Mary Tyler Moore with a leading actress nomination, Sutherland was ignored (as he has been throughout his 50 years in film). So encouraged, Redford continued directing, carefully choosing projects within his personal comfort zone. His second turn behind the camera, 1988's The Milagro Beanfield War, was a critical rather than a financial success, as was his third, A River Runs Through It (1992). Redford earned his second best picture and director Oscar nominations for 1994's Quiz Show, a dramatic examination of the television scandals of the 1950s, evocatively filmed in black and white. To date, he's directed nine features. Among his most lasting contributions to filmmaking, though, is the creation of the Utah-based Sundance Film Festival, a showcase for independent production first held in 1978.