Friday, September 3, 1971

LAST SATURDAY EVENING [Aug. 28, 1971], as delegates to the first World Shakespeare Congress gathered for its closing ceremonies, Congress planning committee co-ordinator Temple Maynard clapped his friend Rudolph Habenicht on the shoulder.

"Rudie," he said, "this is an historic occasion."

Habenicht laughed. For five years, the two had often broken off a late-evening planning session with those same words. Now they could both laugh. The deed was done, and it had indeed been an historic occasion.

For eight days, 500 delegates from 30 nations had run enthusiastically with the ball that Habenicht had first thrown out nearly five years before.

In the words of the University of Toronto's Clifford Leech, the Congress had been borne aloft on "the vision of Rudie Habenicht."

"He talked about it and told people that it was a good vision and that they must come to believe in it," Leech said. "We were converted."

Among the important early converts who came forth for Shakespeare were England's Terrence Spencer, director of Stratford's Shakespeare Institute, and Pennsylvania State's Harrison Meseroe, bibliographer for the Modern Languages Association.

In fostering his new faith, Habenicht had a built-in advantage. As bibliographer for the Shakespeare Quarterly's annual World Bibliography, he was already in correspondence with many of the top men in the field. He wrote to them all and waited.

His first respondents were excited, encouraging and prophetic. From Munich and Tokyo Universities, Wolfgang Clemen and Jiro Ozu each wrote to say how enthused they were with the idea of a world Shakespeare congress. From opposite sides of the globe, Habenicht's idea had echoed back. Shakespeare's world wanted to get together in Vancouver.

At the conclusion of last week's congress, it decided that it wanted to stay together. Its two key investigative committees, those dealing with international relations and problems of bibliography, recommended that lasting ties be the result of their meeting.

The congress in plenary session unanimously approved the motion of Birmingham University's John Russell Brown that a continuing committee of the congress be set up to work for the establishment of an international Shakespeare association.

According to Brown's report, such an association would serve to link existing national associations, provide an information centre from which they could all draw, keep a running diary of continuing work in the theatre, classroom and conference hall, and consult in the planning of future World Shakespeare Congresses.

The bibliographic committee, under Harrison Meserole, recommended the establishment of a single, central data bank tied into a sophisticated computer system. Not only did he see such a centre providing for the needs of the world-wide Shakespeare community, but it could also solve many of the problems posed by the international information explosion.

"We can discover new tools and nomenclature in the experience of the theatre," Princeton's Daniel Seltzer had said in an earlier session. He later added: "We should be looking for a common ground between what we have learned and the ways we teach, and the way directors evoke reality."

Taking a different tack, John Russell Brown suggested that what was needed was "a new approach to theatrical set pieces in which the audience response is predefined by costumes, sets and directional interpretation.

"I want it to be free, open and active," he said. "Going to a play should be like going to a game. The audience should wonder 'how is it going to work out tonight?'"

Taking up the same thought later, he said: "New things should lead us to a new kind of bare Shakespeare. Not nude," he added quickly, "but bare."

It was New York State's Stanford Sternlicht who caught the mood of the congress most simply. "I hope that this congress will help shift the balance, and give academics more of a place in the theatre." As for future congresses, the delegates in plenary session unanimously approved a motion calling for greater participation by theatre people in them.

The emphasis on theatrical experience couldn't have pleased anyone more than Al Grant, president of the Toronto-based paperback publishing house called Festival Editions. Festival was among the 13 publishers displaying their Shakespeareana at the congress, but it was the one with the newest idea.

"Shakespeare is not literature," Grant said. "He wrote for the stage. He was primarily an entertainer. Shakespeare is movement, action, emotion — everything that's related to drama."

Accordingly, his classroom editions — including Romeo and Juliet, Julius Caesar and The Merchant of Venice — are working scripts based on actual productions mounted at Ontario's Stratford Shakespeare Festival. Notes, written by the director responsible for the original,

are provided for each scene as well as his full stage directions.

The series, begun last year, competitively prices its numbers at 75 cents each. The Stratford Festival, which cooperates fully in their production, is rewarded with a royalty.

"'Our revels now are ended'," quoted the University of B.C.'s J.A. Lavin, congress executive secretary, as he brought the closing ceremonies program to order, "and those of our chartered accountants are about to begin."

The final cost of the congress was nearly $150,000. Major contributions of slightly more than $30,000 apiece came from Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia and the Canada Council.

"From the point of view of the Council, this is one of the most important events ever to happen here," said Marcia McLung, the special projects officer responsible for administering the Canada Council grant. "This is the largest conference grant we've ever given."

The federal body made its decision on the basis of its importance which, in this case, includes that of the congress to the people involved, and its interest to people in the wider cultural sphere which, in this case, includes the theatre and films. "As far as we're concerned," she said, "it's been money well spent."

(By contrast, the provincial government, which has constitutional jurisdiction over educational matters, made no initial contribution. As a last-minute gesture, the Centennial Committee offered to pick up the cheque for a catered luncheon for congress delegates. Social Credit party backbencher Robert Wenman, a former school teacher, addressed the gathering. Excluding the MLA's traveling expenses from his Delta home, the total cost of the affair was $1,773.).

For their investment, the operators got what Martin Lehnert of East Berlin's Humboldt University called “the most important and successful Shakespearean congress of our time."

On thousands of miles of magnetic tape are recorded the collective insight of a multitude of progressive men. The voices tell the story.

Mixed together are the mellow, rolling tones of Shakespeare's own England, the crisp precision of Germany, the gentle music of Japan, the flat dynamics of the U.S. and, blending in with them all, the quiet, comfortable confidence of the Canadian hosts. The sound is of a concert rather than a cacophony.

Or, to put it in the words of Nico Kiasashvili of the Soviet Union's Tbilisi State University: "The sciences have had their day. Now it is the turn of the humanities."

Their investment, born of a dream, has bred yet another dream. Already Rudie Habenicht has had a vision of a second congress, one which he has shared from the start with Soviet filmmaker Grigori Kozintsev, New York State University's Jan Kott, John Russell Brown, Malavetas and Kiasashvili.

They see a ship, filled to the gunnels with convivial Shakespeareans, setting sail on an August tide — Leningrad, Copenhagen, Amsterdam and London among her ports of call. They see glorious sunsets and even more glorious sunrises.

And who's to say their dream won't come true?

"It's hard," said Carol Gadd, chairwoman of one of Habenicht's intensely loyal student committees, "to separate the idea of the congress from Rudie's idea of the congress.

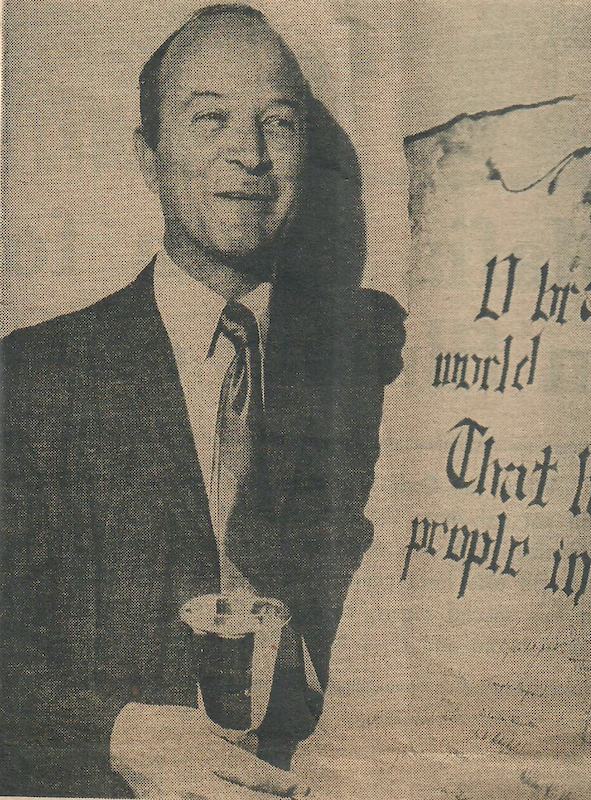

Sunday evening [Aug. 29, 1971], in appreciation of their unceasing enthusiasm, Habenicht gave a party for his corps of student volunteers. At its height, the young friends, with whom he had shared his dream and to whom he had dedicated his congress, presented him with a gift.

It was a silver goblet. Quickly, he filled it with a draught of Malavetas' good Greek wine. A toast was hardly necessary. There, engraved in flowing script on the goblet itself, was Shakespeare's own best toast to the memory of the first World Shakespeare Congress and the dream of the second:

O brave new world,

That has such people in’t.

The above is a restored version of a Province Spotlight Magazine feature by Michael Walsh originally published in 1971. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Born in Boston in 1925, Rudolph Everett Habenicht joined the SFU faculty in 1966, just a year after the mountaintop university’s 1965 founding. His resumé included wartime service in the U.S. Navy, a masters degree from Columbia University, a Ph.D. from Oxford University’s Merton College and eight years as professor teaching at the University of Southern California. He was 47 when he realized his vision of a World Shakespeare Congress, 55 when he retired from SFU, and 82 when he died at his home in Sequim, Washington.

Congressional record: Reeling Back’s WSC archive consists of a Preview feature followed by my Opening report, a Tuesday report, a Wednesday report, a Thursday report, a Friday report, a First Folio feature about a family with links to both Shakespeare and Vancouver, a Saturday report, a Closing report, and my Summary feature.