Friday, May 31, 1991.

SHADOW OF CHINA. Co-written by Richard Maxwell. Based on Masaaki Nishiki’s 1985 novel Snake Head. Music by Yasuaki Shimizu. Co-written and directed by Mitsuo Yanagimachi. Running time: 131 minutes. Rated Mature with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: "occasional violence and coarse language.”

SECRETS? IN HONG KONG, everybody has at least one.

Take Lee Hok Chow (Roy Chiao), for example, the owner of the Crown colony's largest Chinese-language daily newspaper. Lee's cashflow is secretly supplemented by drug dealing.

Mr. Wu (Dennis Chan), part of the Old Establishment, is a member of a secret organization connected to Hong Kong's future overlords in Beijing. Wu is actually looking forward to the end of British rule in 1997.

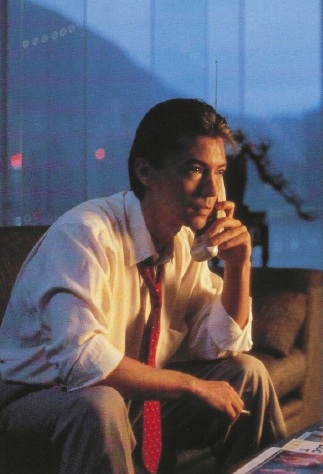

And then there's Henry Wong (John Lone), one of city's most successful new

entrepreneurs. Once known as Wu Chang, he was a Chinese Red Guard leader.

When Mao died, he fled the Mainland for a new life as a capitalist. Now, Wong is planning the secret takeover of Lee's paper because "I want to be the voice of Hong Kong."

Into this shadow world comes a naive Japanese journalist named Akira (Koichi Sato). A bumbling sort, he's looking for the lost offspring of one Katsuo Obayashi, a Japanese spy who served in China during the war.

In Shadow of China, director Mitsuo Yanagimachi's modern dress Tai-Pan, past and future converge. Ambitious and emotionally complex, it attempts to unravel the Gordian knot of interests and influences at play in today's Far East.

Actor Lone, who had the title role in Bernardo Bertolucci's The Last Emperor, has just the right mixture of charisma and authority as boy wonder Henry Wong. A man with a past, Wong makes his move against Lee's enterprise, secure that "the old bandit has more to hide than I do."

Significantly, their financial drama plays itself out over the same few days as the events in Beijing's Tiananmen Square [June, 1989]. Complicating Wong's life is the reappearance of his old girlfriend and fellow refugee Gloria Moo-Ling (Vivian Wu, Lone's Number Two Wife in The Last Emperor). Unbeknownst to Wong, she's been making a life for herself as a lounge singer, and is now keeping company with the inquisitive Akira.

Based on Masaaki Nichiki's 1985 novel Snake Head, the story was adapted for the screen by Richard (The Serpent and the Rainbow) Maxwell. Unfortunately, he has burdened Yanagimachi's international cast with some rather lumpish dialogue in an attempt to further the plot.

"Moo-Ling," Akira says in one particularly clanging speech. "He's not the boy you knew in Shanghai. He's smuggled guns, drugs, people!"

Well, yes. The question is why.

While Shadow of China reveals Wong's secrets, it's less clear on his purpose. In the end, Yanagimachi's picture confuses the very issues it sets out to address.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1991. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Though it didn’t play Vancouver until mid-1991, Shadow of China was a 1989 Japanese-American co-production, shot in English on location in Hong Kong. While the world’s attention was on the Soviet Union — after three year of political unrest, the Eurasian superpower collapsed on December 26, 1991 — seismic shifts were occurring in the Far East. Mitsuo Yanagimachi's feature insisted that we should be paying attention to the emerging importance of the People’s Republic. It took a generation for U.S. policy makers to notice the obvious, and in 2009 the Obama administration began its “Pivot to East Asia.” For reasons that make no positive sense, subsequent American Presidents Trump and Biden have bought into a confrontational international narrative. If geopolitics in 2022 gets made into a movie, it’s difficult to see how it could have a happy ending.

So, let’s talk about the geopolitics of the movies instead. For as long as there has been a Hollywood, America’s filmmakers have lusted after foreign markets. China’s current population of 1.4 billion is more than four times that of the U.S., which makes it singularly attractive. The infrastructure — China boasts some 78,000 cinema screens versus about 41,000 in the U.S. — is in place. Unfortunately for studio executives, running the show is more complex than in American vassal states like, say, Canada. The PRC is just not into being told what to do.

Three years ago, in a report called How China Is Taking Control of Hollywood, the corporate-sponsored Heritage Foundation fretted that “a global power shift in entertainment” was taking place. Glossing over the historic fact that corporate movie-makers will do absolutely anything for money, it warned that “major Chinese production companies (are) teaming up with Tinseltown, which is leading to concerns over pro-China propaganda making its way into major American blockbusters.” Heritage, in the business of promoting right-wing political narratives, lamented that nativist American cinema was losing faith in its pro-U.S. propaganda mission.

Last September, in an article titled How Hollywood Sold Out to China, the monthly Atlantic magazine framed essentially the same story as “a cautionary tale.” It noted that “in 2020, the Chinese film market officially surpassed North America’s as the world’s biggest box office, all but ensuring that Hollywood studios will continue to do everything possible for access to the country.” Although reporter Shirley Li acknowledged that “during the blacklist era of the 1940s and ’50s, Hollywood studios infamously submitted to domestic political pressure,” she doesn’t bother mentioning the military-entertainment complex overseen by the U.S. Department of Defense since the establishment of its entertainment liaison office in Los Angeles in 1946. In exchange for script approval, the Pentagon provides access to locations, personnel and equipment such as jet fighters and aircraft carriers. Put another way, show business is a business, and always has been.

Canadian connections: Shadow of China star John Lone’s first leading role was as Charlie, the thawed-out title character in director Fred Schepisi’s 1984 made-in-B.C. feature Iceman. In 1985, he co-starred in Michael Cimino’s Year of the Dragon, another movie that involved location work in Vancouver. Playing the title role in David Cronenberg’s 1993 M. Butterfly took him to Toronto, and he returned to Vancouver to co-star in J.F. Lawton’s 1995 martial arts thriller The Hunted.