Saturday, December 7, 1974

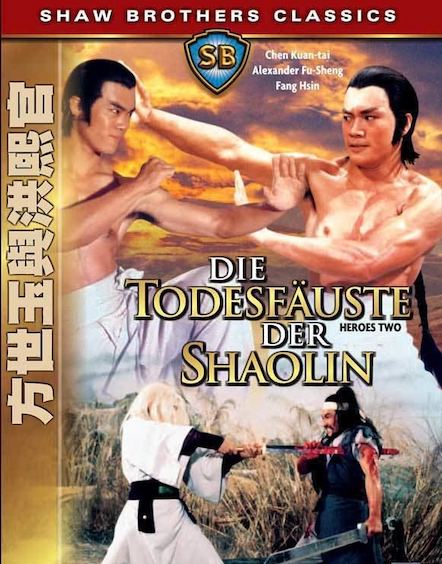

HEROES TWO. Co-written by Ni Kuang. Music by Fu-ling Wang. Co-written and directed by Chang Cheh. Running time: 93 minutes. Rated Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: violence throughout. In Mandarin with English and Chinese subtitles.

HEROES TWO MAY NOT be the best kung-fu film ever made. It is, however, by far the best I’ve seen.

Understand, now, I’ve never been a real fan. Since kung-fu became an action-film trend some 18 months ago [mid-1973], I’ve seen about half a dozen, all more or less in the line of duty.

All of them were dubbed. Some of them featured the genre’s superstar, the late Bruce Lee (dead over a year, and soon to been in an exciting new “lost” film), and none of them appealed to me. All so much kung-foolishness.

Heroes Two, currently at the Shaw Theatre, is different. Directed by Hong Kong filmmaking veteran Chang Cheh for his own company, the film has a good deal of respect for the taste and intelligence of its audience, a respect it demonstrates in a number of tangible ways.

One is a basically sensible storyline. Set in 17th century Canton, the film opens with the destruction of the Shao Lin monastery by the invading Manchus, an understandable act, since the brothers are all practising martial artists and would be the natural leaders of any local resistance movements.

The best of the monks manage to escape, and Chang’s story chronicles the Manchu’s efforts to track down and suppress their followers.

Another feature is believable characters. In previous martial arts epics the roles seemed virtually interchangeable. Good guys, bad guys — unless the evildoers had fangs, they were hard to tell from the heroes.

No such trouble here. Not only do the principals fight well, but they act equally well. Hero Fang Shih-yu (Fu Sheng) is every bit as cocky as the late Lee, but brings to his role a charm that the cold-blooded superstar never managed to muster.

Hero Hung Hsi-kuan (Chen Kuan-tai) is more thoughtful and long-suffering, but conveys it all without exaggerated histrionics. Their adversaries, the Manchu General Kang Che (Chu Mu) and his henchman Teh Hsiang (Wang Ching), wear their black hats without losing any of their sharp human dimensions, a fact that makes their villainy all the more effective.

Chang’s film is definitely for the kung-fu cognoscenti. The program begins with a 15-minute short, in which the heroes demonstrate their action specialties. That opener also makes his movie accessible to martial-arts novices — me, for example — who will begin to recognize characteristic strategies during the feature’s ballet-like battles.

Heroes Two is a kung-fu film for people who don’t like kung-fu films.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1974. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Monday, March 31, 1975

THERE SEEMS TO BE some confusion over which of the Shaw Theatre's current attractions came first. According to San Francisco City Magazine writer Michael Goodwin, "Heroes Two (is) the middle film of a trilogy comprising, in order, Men from the Monastery, Heroes Two and Shao Lin Martial Arts."

On the other hand, both the U.S. trade paper Variety, and the British Film Institute's authoritative Monthly Film Bulletin suggest that Heroes Two is the original and Men From the Monastery is the sequel.

What is clear is that film buffs on both sides of the Atlantic have discovered that there are "better" martial arts movies, and have begun to take them seriously. Attempts are being made to sort out the confusion of name changes, directors and performers as well as to analyze what MFB reviewer Verina Glaessner calls "one of the more interesting developments in recent Chinese film."

Receiving much attention is veteran Hong Kong director Chang Cheh. His recent amicable split with the multimillion-dollar Shaw Brothers organization is the "development" to which Glaessner refers. Although internationally distributed by Shaw, the Shao Lin trilogy was developed and produced for his own company, Chang's Film.

As to their order, I'm inclined to agree with Goodwin. Viewed together, Men from the Monastery looks like Chang's practice run for the technically more sophisticated, dramatically satisfying Heroes Two.

Both films are set in the same period and place: 17th century Canton. China's Ming dynasty has been toppled by Manchu invaders, but loyalist sentiment still burns in the Shao Lin monasteries.

Both films feature the same central characters. Young, cheeky and thoroughly charming is hero Fang Shih-yu (finely played by Chang discovery Fu Sheng). Thoughtful, serious and darkly brooding is hero Hung Hsi-kuan (played by All Southeast Asia Kung-fu Champion Chen Kuan-tai).

Where the films differ is in the basic dimensions of their story canvas and the degree to which each concentrates on battles and brawls to the exclusion of plot. Men from the Monastery, the more violent of the two, is less realistic.

Structurally, it is an anthology of four virtually independent episodes. The first introduces Fang Shih-yu, a Shao Lin brother who proves himself a martial arts master long before his formal education is completed, and who then returns to his home village to do battle with a hated Manchu leader.

The second episode belongs to Hu Hui-chien (Chi Kuan-Chun) a businessman's son who takes on a gang of Manchu masters to avenge the murder of his father. Despite his righteous anger, he's no match for the more skillful Manchus.

He is beaten up several times before Fang comes along to advise him to go to the Shao Lin school. Three years later he returns, a master, to have his revenge.

The third segment focuses on Hung Hsi-kuan, a patriot leader in hiding. "I kill Manchu dogs," he announces before dispatching a couple in the street. His dedication to his hobby causes the Shao Lin monastery to be razed.

In the final episode, the three heroes, with 10 companions, battle to the death with an army of Manchus. At the end, only one man is left alive to carry on . . .

If the public was satisfied with Men from the Monastery, Chang Cheh wasn't. His Heroes Two, a film that begins with the destruction of the Shao Lin establishment, narrows its scope to intensify its impact.

In this version, Fang (conveniently resurrected) and Hung do not know one another. Inadvertently, the flip Fang is responsible for the capture of the more serious-minded Hung. Discovering his error, he makes himself responsible for the No. 1 patriot's rescue.

Chang learned several lessons from his first film. This time, for example, he offers filmgoers a pair of villains, General Kang Che and the evil Teh (played by Chu Mu and Wang Ching), who are not only as proficient as his heroes, but whose characters are as well developed. Dramatic as well as physical conflict enters the picture.

At the same time, Chang shows how well he has polished his cinematic technique. There are fewer jarring zooms, fewer close-ups of open wounds, and less artificial blood is shed. Here, his innovative use of monochromatic battle scenes and slow-motion death blows is disciplined to the point where it actually adds to the impact of the final confrontation.

In Heroes Two, Chang has made a film for the Kung-Fu cognoscenti without sacrificing general audience appeal. His films are the first martial arts movies I’ve run across that actually seem designed for people who don’t like martial arts movies.

An action director with an epic sense, Chang Cheh has managed to develop a pair of first-rate characters and evolved a story style that suits them well. The third part of the trilogy is a film worth waiting for.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1975. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Yes, I reviewed Heroes Two twice. The first notice ran on the day in 1974 that Hong Kong-based Golden Harvest Theatres opened a 729-seat cinema in Vancouver’s Chinatown. The new movie house was in direct competition with the 705-seat Shaw Theatre, opened in 1971 to screen the films produced and distributed by Hong Kong’s major moviemaker, the Shaw Brothers. Aware that immediate attention would be on the Golden Harvest initiative, Shaw brought in a proven money-maker from its martial arts library. My first review of Heroes Two ran alongside a review of the Golden Harvest Theatre’s debut feature, 1973’s Back Alley Princess.

The second, longer piece was written four months later, when Heroes Two returned to the Shaw on a double bill with Men from the Monastery. On the first go-around, I wanted to be clear to my newspaper readers about my limitations as a kung-fu film reviewer. Although the genre had been around for two years at the time, I was not entirely comfortable with it. Unlike Westerns, the martial arts movie was rooted in a cultural tradition that was both complex and, well, foreign to me.

In writing the second review I was able to concentrate on a simpler question: which movie came first? Apparently the pictures were shot back to back in 1973. I made the case for Men from the Monastery being first based on the sequence of events in the stories. Another case could be made from their release dates. Heroes Two made it into Hong Kong theatres first (on January 19, 1974), with Men from the Monastery following along on April 3. In the absence of a clarifying quote from Chang Cheh, we may never know for sure.

Fun fact: The film that kicked off the kung-fu film phenomenon in North America (and Bruce Lee’s first starring role) was 1971’s The Big Boss, aka Fists of Fury, a picture that opened in Vancouver (on December 1, 1972) before its March 1973 premiere in the U.S. It was fairly common for distributors to rename genre features imported from abroad. Over the years, Heroes Two has been called Blood Brothers, Bloody Fists, Kung Fu Invaders and Temple of the Dragon.