Friday, June 14, 1974.

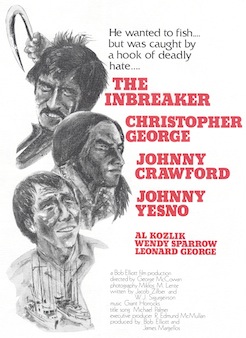

THE INBREAKER. Written by William Sigurgeirson and Jacob Zilber. Music by Grant Herrocks. Directed by George McCowan. Running time: 90 minutes. General entertainment.

LAUNCHED THURSDAY NIGHT BENEATH a sweeping searchlight, The Inbreaker is Vancouver producer Bob Elliott's own little-engine-that-could. A hearty and unpretentious outdoors adventure, the film was shot last summer [1973] in and around Alert Bay.

With an eye for the family trade, he's produced a scenic, uncomplicated movie about a young man who takes a summer job in the West Coast halibut fishery, only to find himself caught up in a conflict that he can neither calm nor comprehend.

Like that famous little engine, Elliott's film has to haul itself up and over a formidable obstacle. In this case, the obstacle is not a mountain, but a lumpishly indifferent script.

Its problems are, on the whole, masked by the overall efficiency and satisfying competence of director George McCowan, his cast and the technical crew. Together, they've managed to make a colourful and attractive film, one that offers audiences a fair share of gripping and memorable moments.

Former child star Johnny Crawford plays Chris McKae, The Inbreaker. An Alberta university student, his education is being financed by his older brother, commercial fisherman Roy (Christopher George). The film opens with a cowboy-hatted Chris arriving in brother Roy's B.C. fishing village.

In an attempt to assert his individuality and shoulder his own responsibilities, Chris has decided that he should work the summer on his brother's boat. The idea has less appeal to Roy, who explains that his is a simple two-man operation.

To take Chris on, Roy will have to fire his deckhand Al (Al Kozlik). If he keeps Al and adds Chris to the crew, he will have to to pay Chris out of his own share of the catch, in which case Chris will still be dependent.

Chris agrees to look for a job elsewhere. As luck would have it, he ends up as an inbreaker — an unpaid apprentice — to Muskrat (Johnny Yesno), an abrasive Indian who just happens to be Roy's most hated rival.

The film's best moments come during Chris's high-seas inbreaking, a period during which the gangling youth is desperately trying to convince his surly mentor of his competence. Adding to his anxiety is the fact that Muskrat, with ringing bravado, has challenged Roy to a fishing contest.

Even with the handicap of an untrained crewman, he will catch more fish, the Indian claims. Roy accepts, thus putting Chrls under double pressure. McCowan, previously a Toronto-based CBC-TV director, has been making his more recent living helming episodes of such tense American shows as Cannon, Run for Your Life, The Mod Squad and The Streets of San Francisco.

In The Inbreaker, he brings together several effective elements: a finely-tuned interplay between actors Crawford and Yesno; a cheerful score by Vancouver composer Grant Horrocks (arranged by Curt Watts to blend in with the chug-chug-chugga-chug-chug-chug of the boat's motor); the visual menace of slashing blades and the random flicking of finger-sized hooks riding a high-speed line.

All are combined to set filmgoers on the edge of their seats.

Having so inflamed the passions between Roy and his rival, screenwriters Jacob Zilber and William Sigurgeirson then resorted to melodrama. Short on ideas, they fell back on an unbelievable series of incidents involving an accidental death, an attempted frame-up, a kidnapping, a murderous chase and a cop-out ending.

Zilber, a creative-writing instructor at the University of B.C. fails to solve the most basic problems of character and conflict definition. Why is there a subtle tension between Roy and his brother? Why does Roy so hate Indians in general, and Muskrat with such particular vehemence?

Why does Muskrat so fear the Mounted Police, "them cowboys," as he calls them? How did an Albertan get into the commercial fishing business, anyhow?

A tighter, more coherent script would have etched in all that information, parcelling it out to the audience through meaningful incident and dialogue. Zilber, apparently unable to solve these problems in the allotted screen time, left it to the director and film editor Werner Franz to imply the missing information without impeding the pace of the finished feature.

That McCowan was able to make palatable entertainment out of The Inbreaker is important not only to this particular film's audience, but to the future of the B.C. film industry. It's worth mentioning that, with the exception of two of his three leading players, all of his resources, both technical and creative, are drawn from Canada's talent pool.

From co-star Johnny Yesno, an Ontario-born actor and broadcaster, to bit player Bonnie Carol Case (who filmgoers will remember as Carol Kane's coquettish girlfriend in 1972's Wedding in White), the performances are of uniformly high quality.

Behind the camera, at virtually every stage of the $400,000 production, the work is equally well done. Thursday, the premiere audience's applause was deserved. Producer Bob Elliot and his new production company are a welcome addition to the local film scene.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1974. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Check out Winnipeg-born George McCowan's brief Wikipedia biography and you'll be told that "he moved to the United States from Canada in 1967 and stayed there." Which, if true, makes it sound as if he departed the Great White North in a fit of pique, slamming the door behind him. In fact, McCowan applied the skills he learned directing stage plays at Stratford's Shakespeare Festival and television drama for the CBC to make feature films on both sides of the border. McCowan made his TV debut directing his then-wife, actress Frances Hyland, in The Salt of the Earth, a 1962 episode of the CBC-TV dramatic anthology series Playdate. His first Canadian theatrical feature, Affair with a Killer, was released in 1966. That 1967 move to the U.S. added much TV series work and at least a dozen made-for-TV movies to his resumé, but he found time to return to Toronto to direct the 1971 hockey romance Face-Off, one of the first domestic features to benefit from Canadian Film Development Corporation funding. His first U.S. theatrical release was 1972's Frogs, a creature feature that has since achieved cult status. In July, 1973, he was on location in B.C.'s Alert Bay directing The Inbreaker, and he was back in Vancouver for 1976's Shadow of the Hawk, a shock-thriller involving some angry First Nations spirits. Daryl Duke, the director he replaced on Shadow of the Hawk, referred to him derisively as "One Take" McCowan. My later review of his Toronto-made science-fiction epic The Shape of Things to Come (1979) was dismissive. Even so, any discussion of Canadian cinema in the 1970s would be incomplete without a consideration of the contribution of George McCowan. He died in 1995 at the age of 68.