Thursday, August 10, 1989

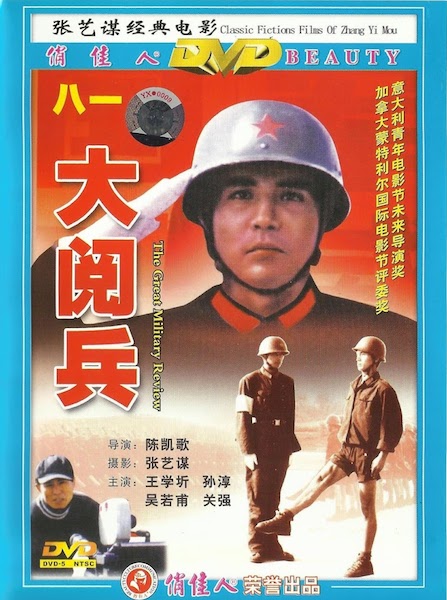

THE BIG PARADE. Written by Gao Lili. Music by Qu Xiaosong, Zhao Qiuping. Directed by Chen Kaige. Running time: 95 minutes. In Chinese with English subtitles. No B.C. Classification. Reviewed with:

WOMAN DEMON HUMAN. Co-written by Zhiyu Li and Guoxun Song. Music by Yang Mao. Co-written and directed by Huang Shuqin. Running time: 106 minutes. In Chinese with English subtitles. No B.C. Classification.

IN BETTER TIMES, THEY came by day.

In 1984, after months of punishing drill, units of the Chinese military paraded in Beijing's Tiananmen Square to celebrate the 35th anniversary of the Peoples Republic.

Later, they would come by night. Not 10 weeks ago [June 4, 1989], an armoured battle group "restored order" in the Chinese capital by violently clearing the square of protesters.

The June assault came as a shock. Pundits, who had been surprised by the boldness of the students, now muttered darkly about a new cycle of repression in the world's largest nation.

All of which serves to lend poignance to the line actor Wu Ruofu, playing Chinese army recruit Lu Chun, hurls at his drill instructor in director Chen Kaige's The Big Parade (1987).

"People want their individuality," Lu tells military careerist Sun Fang (Sun Chun). "Times have changed."

Indicating how they had changed were the stirrings in the world of dianying, the vigourous New Chinese Cinema. Indeed, the six features on view starting tomorrow [August 11, 1989] at the Vancouver East Cinema were picked to showcase the change.

Before the June 4 massacre, Chen's probing service drama, with its barracks humour, questioning attitude towards parade-square extremities and mildly mocking approach to the big parade itself, indicated movement towards a more open society.

The same could be said of Huang Shuqin's Woman Demon Human (1987), a backstage drama focusing on an actress and her search for self-fulfilment. The child of travelling players, teenaged Qiu Yun (Gong Lin) defies her foster father (Li Baotian) to take to the stage when it becomes obvious that she is "a born performer."

Wilful as well as talented, the adult Qiu (Xu Shouli) finds fame playing demon roles in traditional Chinese opera. Her story begins and is punctuated by scenes of her triumphant performance as Zhong Kui, the matchmaking King of the Ghosts.

Huang is proposing a symbolic equation in which the woman, by taking control of China's ancient (male) demons, emerges fully human. Like director Chen's soldier, Huang's actress is saying that times have changed.

Unlike the soldier, she says it to herself. Like Huang, Qiu is a survivor of the Cultural Revolution, an event that is mentioned in dialogue rather than depicted.

In the process, Qiu learned to wear the mask of tradition and live for another day. Her tale suggests that China's new cinema may well be hunkering down today and preparing for "new" new cinemas to come.

* * *

HISTORY ON THE RUN. It may be some time before the events of June 4 [1989] are mentioned in a Chinese movie. Taiwan is another matter. Already in production is We Shall Return, a drama based on the massacre.Developed by Hong Kong director Patrick Tam, the picture will tell the story of a soldier in the Peoples Liberation Army whose girlfriend is a student at Beijing University.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1989. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Not every movie that’s announced gets made. I can find no evidence of Patrick Tam’s Tiananmen Square drama We Shall Return ever being filmed, let alone released. The first fictional feature to include the 1989 events in its story appears to have been director Xie Fei’s Chinese-language Black Snow (Ben ming nian), released in 1990. Two years later, it provided the backstory for Brandon Lee’s Jake Lo character in Dwight W. Little’s Hollywood action film Rapid Fire. Tiananmen wasn’t mentioned again until Hong Kong director Stanley Kwan’s 2002’s Lan Yu, a family crisis drama. Most recently, it figured in the plot of Lou Ye’s 2006 romance Summer Palace (Yi he yuan), a Chinese-French co-production.

Documentarists are more direct about their interest in what Western media call “the Tiananmen Square massacre.” In 1995, PBS-TV’s Frontline series broadcast a three-hour-long look at the protests called The Gate of Heavenly Peace. Director Richard Gordon’s doc drew considerable criticism from the Chinese government. Not to be outdone, Canada’s National Film Board offered up director Wang Shui-bo’s Sunrise Over Tiananmen Square. It picked up a 1998 documentary short subject Oscar nomination for its trouble. More recently CNN correspondent Mike Chinoy directed Assignment China: Tiananmen, a 2014 TV documentary focusing on the journalists who covered the story.

To date, the most compelling commentary on the Tiananmen moment has been British playwright Lucy Kirkwood’s 2013 drama Chimerica. A kaleidoscopic examination of the events and their aftermath, it was a multiple-award winner in London and went on to inspire a TV mini series. (I saw the superb 2019 production mounted by United Players in Vancouver, and can only hope that the mini series makes its way to Canadian television.) By contrast, there is no major Hollywood movie studio willing to touch the subject. It’s been said that China represents the greatest marketing opportunity in American film history, and it just doesn’t make financial sense to risk offending potential production partners. It’s also been said that movie moguls are more interested in making money than making waves . . .