Tuesday, November 2, 1976.

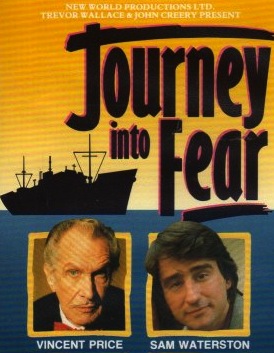

JOURNEY INTO FEAR. Written and produced by Trevor Wallace. Music by Alex North. Directed by Daniel Mann. Running time: 87 minutes. Mature entertainment.

IT'S TAKEN JOURNEY INTO FEAR two years to reach Vancouver, the city where it was financed and filmed. After looking at the finished product, it's easy to see why.

Writer-producer Trevor Wallace is ashamed of it.

And so he should be. What we were promised was an exciting and atmospheric thriller. What we've been given is just bland and confusing.

It turned out that way because too many of the film's imported talents, the high-priced Hollywood professionals, turned out to be incompetent drones. The sad part is that virtually all of the local craftsmen and technicians working under them distinguish themselves.

Announced in early 1974, Journey into Fear was promoted as the biggest movie ever made in Vancouver. Based on Eric Ambler's 1940 novel, it was originally filmed in 1942 with Orson Welles and Joseph Cotten in the starring roles. For his remake, Wallace provided an updated script and hired an international cast.

Journey is the story of a mild-mannered engineer named Howard Graham. In the earlier version he was a munitions expert who became the target of Nazi assassins in Second World War Turkey.

To make his story more contemporary, Wallace changed Graham's specialty to petroleum. If he can he silenced, then sinister Middle Eastern interests will be able to manipulate oil prices upward.

The original film was a dark, claustrophobic item shot completely within the walls of Hollywood's RKO studios. Wallace was determined to open out his version to give the audience the action and scenery not in the original, while maintaining the overall tension. Unfortunately, he failed to inspire his key creative people with the same vision.

Daniel Mann, a 64-year-old former stage director, seems to have exercised no control at all over the film's visual style or the performances of his large, often eccentric cast. Cinematographer Harry Waxman, also 64, apparently received no firm instructions, so he photographed everything with academic indifference.

Faced with a collection of dull, uninspiring visuals, composer Alex North, 66, contributed a flat, uninteresting musical score. In all, Mann, Waxman and North, despite impressive past credits, proved to be tired old men who were conscious just long enough to collect their pay cheques and shamble off to the bank.

Mann's directorial coma left his actors pretty much on their own. Some, like Zero Mostel (as a Turkish office manager) and Shelley Winters (as a Jewish tourist) overworked their hambones, flogging overly familiar schticks.

Others, like Donald Pleasence (as a Turkish undercover cop) and Stanley Holloway (as Winters's long-suffering husband) assessed what was required of them and offered professional if undistinguished performances.

The standouts here are Vincent Price and Yvette Mimieux. Price, as chief villain and Mimieux, as the hero's brief love interest, each took the care to develop their characters beyond the superficial and easily dominate the scenes in which they appear.

The problem is that all of the film's scenes are supposed to focus on the character of Graham, the ordinary man thrust into extraordinary circumstances. This was a part that went to up-and-coming actor Sam Waterston, who brings no life at all to the character.

A massive clot in the heart of the movie, Waterston plays his starring role with all the effectiveness of Barbie's friend Ken, offering the kind of polyurethane performance that made me wish that Price's hired assassin, Ian McShane, was more efficient.

Faced with such problems, producer Wallace seems to have made the only sensible decision: cut and run. At 87 minutes, the final film has been edited within an inch of its feeble life to give the illusion of pace and to provide its distributor with some hope of a few bottom-of-the-bill bookings.

The really sad thing is that in rushing away from an obvious artistic disaster, we miss the considerable technical triumph that Journey into Fear represents for our local production people.

With the exception of three brief exterior scenes — the opening car crash and chases through the streets of Genoa and Athens — the entire project was mounted right here. Every scene was shot either on a set designed, built and lit here, or on a location discovered and dressed by Vancouver movie craftsmen. They deserved better.

As for the rest — Mann, Waxman, North and most especially that underpowered automaton Waterston — their Vancouver vacation has resulted in an unhappy journey into obscurity.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1976. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Journey into Fear slipped into release in the U.S. in early August 1975. Sam Waterston, who'd just played the title role in a New York Shakespeare in the Park production of Hamlet, was already 10 years into his screen acting career. Earlier in the year, he'd suffered critical indifference to his performance in director Frank Perry's modern-dress Western, Rancho Deluxe. Even so, he'd proven to be a fine, if stolid, presence as Nick Carraway, the narrator in Jack Clayton's reverent 1974 adaptation of The Great Gatsby, and he found frequent work. In sharp contrast to the quiet demise of Journey into Fear was the epic failure of director Michael Cimino's Heaven's Gate, the 1980 Western in which Waterston had a starring role. Because of his solid work ethic, Waterston had the good luck to have played the title role in a successful historical drama, Oppenheimer, a BBC-TV mini-series also released in 1980. Overall, the Massachusetts-born actor found his niche playing upright authority figures, a list that includes presidents Theodore Roosevelt (in the 1982 TV mini-series Freedom to Speak) and Abraham Lincoln (in the 1988 TV mini-series Lincoln, and then in Ken Burns's 1990 PBS mini-series The Civil War). His performance as New York Times reporter Sidney Schanberg, in director Roland Joffé's 1984 feature The Killing Fields, earned him an Oscar nomination. He's probably best known, though, for his 16 seasons as attorney Jack McCoy on NBC-TV's Law & Order (1994-2010). Showing no signs of slowing down, he spent the summer playing Prospero in New York's Shakespeare in the Park production of The Tempest (2015). Today (November 13) is Sam Waterston's 75th birthday.