Monday, July 27, 1981.

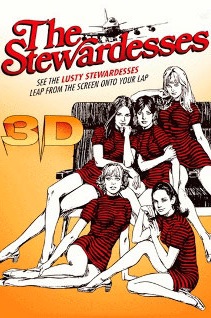

THE STEWARDESSES. Music by James Navas. Written, co-produced and directed by Alf Silliman Jr. Running time: 93 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: Completely concerned with sex.

GOOD MORNING, CLASS. THIS is definitely one of our better turnouts for Cinema Studies 101. You're all here to see The Stewardesses for its historic significance, of course.

As you already know, a severely censored version was shown here 10 years ago [1971]. Approximately 75 minutes of the film played Georgia Street's Strand Theatre in November, 1971.

Even a fragment of the film, a 1969 release in the United States, was too much for Vancouver city officials, though. The subject of a public controversy, it was withdrawn after a brief run.

Canada, as usual, was behind the times. Historically, The Stewardesses represented the end of an era, one that Canadians might have read about (in newsstand magazines such as Time, Newsweek, Playboy or Penthouse) but were not permitted to experience firsthand.

It had begun in 1959, with the release of Russ Meyer's voyeurism comedy, The Immoral Mr. Teas. Simple nudity proved to be a best-seller on urban American movie screens.

For the next decade, U.S. independent film entrepreneurs continued to expand the limits of community tolerance, regularly upping the ante to maintain audience interest. Softcore, or "simulated" sexual activity, became standard screen fare, and the trade paper Variety coined the word "sexploitation" to describe films in which sex (rather than kung fu, car chases or space monsters) was the major marketing (or exploitation) interest point.

By the late 1960s, the major studios routinely were incorporating sex and nudity into their films. As a result, market interest in the lower budgeted sexploitation pictures was falling off.

Today, of course, we know what happened. In 1970, a San Francisco director named Alex de Renzy released Censorship in Denmark, a "documentary" feature that stepped over the line to offer audiences hardcore screen sex.

Hardcore (or pornography) had always been present as the logical next step. Before taking that step, though, producer Louis K. Sher —whose Sherpix company later distributed the de Renzy feature — wanted to try something else.

That "something else" was 3D, the stereoscopic film process that provides filmgoers with the illusion of seeing in three dimensions. The picture was writer-director Alf Silliman Jr.'s The Stewardesses.

Today, the picture is an artifact. Knowing when it was made and why, we can appreciate its coy circumspection and its plodding catalogue of non-explicit sexual activities.

Restored to its original length — approximately 93 minutes — the picture's episodic plot betrays the fact that the film was stitched together from a number of otherwise independent film shorts. Our heroines — there are at least seven — are crew-mates on Pacific Sierra Airline's Honolulu-to-Los Angeles flight.

They go their separate ways during an 18-hour layover. Rookie flight attendant Tina Andrews (Paula Erikson) settles in with pilot Brad Masters (William Basil) who, in what appears to be a fantasy sequence, is shown to be PSA's foremost layover Lothario.

Both Samantha Allen (Christina Hart) and Wendy Blake (Janet Wass) pick up passengers. Wendy, something of a social worker, takes home a Vietnam-bound soldier (Andy Roth), while the more ambitious Sam goes out to dinner with advertising executive Colin Winthrop (Michael Garrett), a TV-commercial casting director.

Annie (Donna Stanley), the partying type, heads for a bar that caters to flight crews. Karen (Patrica Fein) prefers the more solitary pleasures of drugs and masturbation, so she goes home alone.

Chubby Josie Peters (Angelique de Moline), the chief stew, also eschews male company. Her target for tonight is Kathy Edwards (Cathy Ferrick).

As befits an artifact, The Stewardesses contains elements of period nostalgia. Remember, for example, when miniskirts were the fashion and tan lines were the ultimate in cheesecake sexiness?

Director Silliman's use of his 3D technology is about as imaginative as his screenplay. Except for an amusement park dark-ride sequence, the picture's cinematography does little more than add the depth illusion to a series of standard camera set-ups.

Being shown at the Savoy in StereoVision 3D, the uncut Stewardesses retains its 1971 B.C. Classifier's warning "completely concerned with sex."

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1981. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: The female flight attendant's place in American popular culture is complex, to say the least. Just three years after Ellen Church — who had applied for work as a pilot — made her debut flight as BAT's head stewardess, Hollywood's Columbia Pictures released Air Hostess (1933). B-picture beauty Evalyn Knapp played the title role in the first aviation thriller to feature a sassy stew. Though mostly seen in movie supporting roles, the flight attendant occasionally took centre stage. The 1956 Doris Day drama Julie is memorable for being the first film in which a woman saves the day by piloting an airliner to safety. (By 2005, the year critic Ron Hogan published The Stewardess Is Flying the Plane! American Films of the 1970s, the heroic flight attendant had become a commonplace plot device.) For the most part, though, filmmakers preferred characterizing stewardesses as girls who just wanted to have fun. In 1967, the best-seller Coffee, Tea or Me? became their textbook. Purportedly the "memoirs" of hot-blooded Trudy Baker and Rachel Jones — it was the work of genre novelist Donald Bain — it might well have inspired The Stewardesses screenwriter Alf Silliman Jr. (the nom de plume of Los Angeles-born Allan Silliphant).

Silliphant, who also co-produced and directed the 1969 feature, had a genuine interest in both aviation and the stereoscopic film technology developed by his partner (and Stewardesses cinematographer) Chris Condon. In his 2012 book, 3-D Revolution: The History of Modern Stereoscopic Cinema, film historian Ray Zone tells us that their picture's original budget was $14,000. During the first two years of its release, it grossed "over $11 million." In 2009, its domestic film rentals were estimated to have exceeded $141 million. Applying the industry standard of comparing profits to production costs, The Stewardesses turns out to be the most successful 3D movie ever made. In 1970, Condon and Silliphant used their share of the picture's profits to found the California-based charter service Trans Sierra Airlines. Later renamed Sierra Pacific Airlines, it relocated to Tucson, Arizona in 1976 and remains in operation to this day (2016).

In 1969, the partners patented the single-camera 3D motion picture lens used to make The Stewardesses. The technology became the basis for their 1971 company, StereoVision International and, over the next 25 years, about 36 features were made in the process. Condon and Silliphant are often credited with the revival of 3D in the 1970s that resulted in such 1983 big studio releases as Jaws 3-D, The Man Who Wasn't There and Spacehunter: Adventures in the Forbidden Zone.

Addendum: On the morning the above item on The Stewardesses was posted, Simon Fraser University's Daniel Say wrote to tell me of Aussie aviator Charles Kingsford-Smith's Vancouver connection. Born in 1897, he was six when his family moved to B.C., and 11 when they moved back to Australia. His memory is much honoured down under where Sydney's international airport (and home base to Qantas Airways) is named for him. His brief time in Canada was recalled in 1955 with the opening of the Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith Elementary School in Vancouver's Victoria Fraserview neighbourhood. The local school's crest, displayed on its website, features his most famous aircraft, the Southern Cross.