Thursday, August 25, 1971.

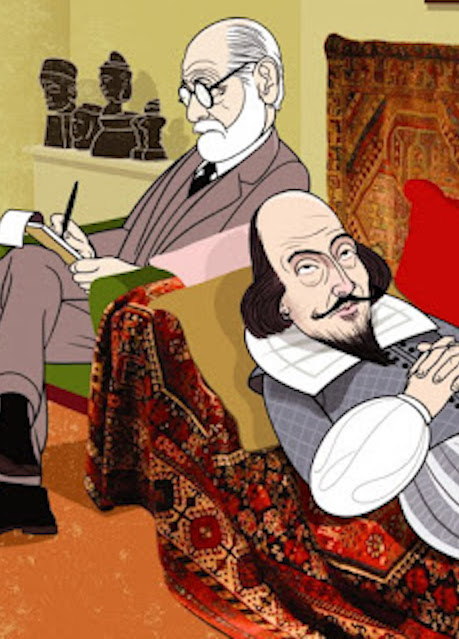

A CLUTCH OF PSYCHOANALYSTS, clinicians and critics put Shakespeare on the couch Wednesday [Aug. 24, 1971] and concluded that the Bard could have used some help.

Starting out as a writer of erotic love poetry, Shakespeare nurtured deep-seated anxieties about marital relations at the parental level. According to C.L. Barber of the University of Santa Cruz, women dominated his love poetry, his histories were underscored by the theme of the motherland and the comedies, though never offering a clear challenge to male dominance, nonetheless give scope to women in transvestite roles.

The tragedies, on the other hand, show the mature Shakespeare seeking a negative resolution for an Oedipus complex. In them he tries to find a figure who could be his father, Barber said.

Although successive male figures are tried, they are all found wanting. Unhappily, said Barber, no male identity proved adequate.

Not completely sure whether the Freudian approach provides insight or effrontery, delegates to the World Shakespeare Congress made the psychoanalysts' symposium the most heavily attended of Wednesday's five simultaneous special sessions. An overflow audience was shifted out of a regular classroom into a full-sized lecture theatre to accommodate their curiosity,

Objects of their interest were the long-time pariahs of the scholarly world, the critics who seek to apply the techniques of psychoanalysis, with its probes into the unconscious sexual nature of man, to literature. The Freudians, for their part, have been lurking in the background for over 60 years.

The idea of delving into the subconscious lives of fictional characters, and ultimately through them into the minds of their authors, comes from Sigmund Freud himself. The first psychiatrist once suggested in the footnote to an essay that the vexing problem of Hamlet could be explained with reference to the Oedipal complex.

Ernest Jones, Freud's friend and biographer, took up the idea and ran with it. In 1910, he produced the first version of his book Hamlet and Oedipus. Thus began the slow popularization of a new analytical tool.

Despite three generations of work, the conventional academic community has never fully accepted the psychoanalysts. Their presence at the Congress, opposed by some delegates, was a small breakthrough for their point of view.

The nine-man symposium did their best to exploit it to advantage, presenting the largely open-minded audience a kaleidoscopic picture of their current efforts.

"Let's go back to first principles," suggested New York State University professor Norman Holland. "Why use the psychoanalytic approach?" he asked, and then quoted a sign fixed above a telephone at one end of the lecture hall:

"Direct line to audio visual centre. Use this phone to report difficulties or breakdown of equipment."

Psychoanalysis, he said, was the only branch of psychology that dealt with particular works and related them to minds. It could, he continued, open the minds of the character, of the collective whole of a play, of the author and of the audience to study.

Their approach provides a work of art with an underlying continuity in terms of the life of the hero and the kind of imagery used, said Dr. David Barron of Des Plaines. This allowed the development of a wholesale pattern in a work, he said.

It isn't the only approach, admitted New York State University's Murray Schwartz. But it does show the unconscious unity in a work, the unity derived from the deeper coherence of mind that cannot be consciously created.

The critical understanding developed by the psychoanalyst helps the viewer to share the feelings of the characters, added the University of Victoria's M.D. Faber. Dropping his chairman's neutrality to comment on the discussion, Faber said the approach breaks down the hidden barriers so that an audience's response is enriched.

Though somewhat defensive in tone, the discussion ranged widely. Macbeth and Timon of Athens were viewed as victims of oral vulnerability, Falstaff as Prince Hal's father surrogate and A Midsummer Night's Dream as a quest for the authentic self.

Responses by delegates ranged from enthusiastic to coolly hostile. Many had come for what they considered the symposium's entertainment value. One questioner recalled the 19th-century critic who took all the sexual parts out of Shakespeare and whose name, Bowdler, has become synonymous with use of the blue pencil.

He asked if, in light of director Peter Brook's recent returning of all the sex to A Midsummer Night's Dream, the new term should be "Peterizing?"

More affirmative was Princeton's Danial Seltzer. The psychoanalysts' work was, he said, pertinent to stagecraft. Actors require human terms and experience to come to an understanding of their roles.

The psychoanalysts' work was helping to put the bard where he belongs — on the stage.

The World Shakespeare Congress is jointly sponsored by Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia and the Canada Council. Sessions of the congress are being held on both campuses.

The above is a restored version of a Province feature report by Michael Walsh originally published in 1971. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In her 2015 book Shakespeare and Psychoanalytic Theory, University of San Francisco professor Carolyn E. Brown tells us that ”Shakespearean psychoanalytic criticism burgeoned in the 1980s.” The book she identifies as “the first anthology devoted exclusively to psychoanalytic readings of Shakespeare” is Melvin D. Faber’s The Design Within: Psychoanalytic Approaches to Shakespeare, published in 1983. Faber was the University of Victoria professor who chaired the 1971 symposium that I covered in the above report.

Later the same year, I reviewed Roman Polanski’s controversial adaptation of Macbeth,

Congressional record: Reeling Back’s WSC archive consists of a Preview feature followed by my Opening report, a Tuesday report, a Wednesday report, a Thursday report, a Friday report, a First Folio feature about a family with links to both Shakespeare and Vancouver, a Saturday report, a Closing report, and my Summary feature.