Monday, January 9, 1984.

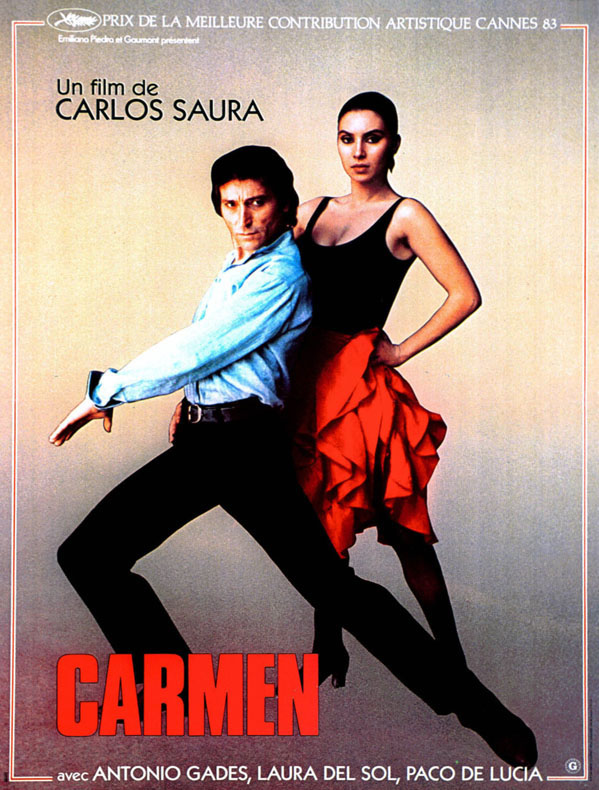

CARMEN. Co-written and choreographed by Antonio Gades. Based on the 1846 novella by Prosper Mérimée. Music by Paco de Lucia, with selections from the 1875 opera by Georges Bizet. Co-written, choreographed and directed by Carlos Saura. Running time: 99 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier’s warning: occasional very coarse language and nudity. In Spanish with English subtitles.

HER STORY, A TALE of passion and honour, gypsies and toreadors, seems to distil the essence of Spain. Ironically, Carmen, as both a novella and an opera, is the creation of Frenchmen.

Antonio (Antonio Gades) is able to quote by heart author Prosper Mérimée’s evocative descriptions of the wolf-eyed temptress. A dancer, he is determined to redo composer Georges Bizet’s opera as a classical Spanish ballet.

Antonio is fired by more than cultural patriotism. He is convinced that Carmen really does contain an intensely Spanish feeling, a duende that can only be fully expressed in the flamenco style.

In bringing his version of Carmen to life on screen, Spanish director Carlo Saura faced some major problems. Like his character Antonio, he has long been impressed with the fact that Carmen is "not only a grown woman, but a mythical figure, a universal myth."

Together with his friend, Spanish National Ballet director Gades, Saura wanted to wed the story to dance. True to his calling as a movie-maker, he also wanted his film to be accessible to the widest possible audience.

Saura solves all these problems in his Carmen, a film that has both the vitality and the emotional drive of a Bob Fosse drama. Like Fosse’s All that Jazz (1979), Saura’s picture opens with dancers auditioning for parts in the new production.

Antonio is involved in a search for the perfect Carmen. He himself plans to dance the role of Don José, the lovelorn Basque cavalryman whose obsession with the sensuous gypsy girl brings about his tragic downfall.

Eventually, he casts a young cabaret dancer whose name really does happen to be Carmen (Laura del Sol). As the company develops its ballet, fantasy and reality blend together. Carmen becomes Carmen for Antonio, and the tormented spirit of Don José begins to replace that of the aging master choreographer.

Although dance is integral to his story, Saura does not assume an audience of aficionados. He uses the film’s rehearsal-hall milieu to painlessly pass along information that helps those of us not well versed in the intricacies of flamenco to more fully enjoy what we are shown.

The arrant nonsense of Fame (1980), Flashdance and Staying Alive (both 1983) left me wary of "dance" movies. Carmen, by contrast, is a sophisticated, refreshingly adult backstage fantasy.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1984. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: As I noted in my review of director Francesco Rosi’s 1984 Carmen (an adaptation of the original opera), the 1875 premiere production “was savaged by the critics and shunned by the public.” Composer Georges Bizet broke with the content conventions of his day — a story that featured impoverished characters indulging in lawlessness and immorality was nothing if not controversial — and the result was a shocked and scandalized audience. Within ten years, it would be recognized for its brilliance, and go on to fame as one of the greatest operas of all time.

Today, Carmen is controversial yet again. This time the concern is over the use of the word “gypsy” to describe its tempestuous, tragic heroine. According to a 2020 posting by travel blogger Alex Schmidt: “Gypsy is straight-up racist, similar to using the n-word. The word is a racial slur against the Roma people, the PC term for gypsy.” I was blissfully unaware of this until earlier this year. As we were posting my 1994 review of Monkey Trouble, my executive editor pointed out that the original notice contained the phrase “gypsy organ grinder.” She pointed out that the word was one we ought not to use anymore.

Change has been a long time coming. In 1971, representatives of the people we’ve always called “gypsies” (because of the mistaken belief that their ethnic origin was Egyptian), gathered in London for the 1st Romani Congress. There the collective term “Roma” was adopted. Their organizing since then has led to such bodies as the United Nations and the Council of Europe to add Roma to their official vocabularies. As early as 2001, the name issue was making it into U.S. news stories about racism in Eastern Europe. In the meantime, the use of the term “gypsy” in the popular culture remains an evolving issue.

Use the word "gypsy" in a simple title search on the IMDb website, and you’re offered a list of 200 feature films, made-for-TV movies and TV series episodes. Add that to several centuries of stereotypical representations in the Western literary tradition, and you have a lot of deep-seated preconceptions to overcome. Yes, gypsies will remain a part of our collective imagination for a long time to come. The trick is to understand that they’re part of a fictional past, and that we now need to use the g-word conscious of its historic context. In other words, Carmen does not represent the Roma reality.