Tuesday, November 27, 1990

AKIRA KUROSAWA’S DREAMS (Yume). Music by Shin’ichirō. Written and directed by Akira Kurosawa. Running time: 119 minutes. Rated General with no B.C. Classifier’s warning. In Japanese with English subtitles.

Episodes: 1 - Sunshine Through the Rain; 2 - The Peach Orchard; 3 - The Blizzard; 4 - The Tunnel; 5 - Crows; 6 - Mt. Fuji in Red; 7 - The Weeping Demon; 8 - Village of the Watermills.

AMONG MOVIE BUFFS, HE needs no introduction. Japan's Akira Kurosawa has been recognized as one of the world's great directors for more than 35 years.

Honours, tributes and peer approval guarantee his place at the banquet table. He won his first Oscar in 1951, carrying home the foreign language picture prize for the influential Rashomon.

In March [1990], George Lucas and Steven Spielberg stood together before a live television camera to present birthday greetings and a lifetime achievement Academy Award to the 80-year-old director.

Kurosawa is, Spielberg said, "a man many of us believe is our greatest living filmmaker."

What becomes a legend facing honourable retirement?

Should he rest on his laurels or continue to take risks?

In Kurosawa's case, the choice was between ending with a Lear (1985's Ran) or attempting a Tempest. No quitter, he created a new challenge, a personal summing up called Akira Kurosawa's Dreams.

Made up of eight episodes, Dreams offers filmgoers Kurosawa's own "ages of man." Each is a self-contained moral fantasy in which the writer-director presents a version of himself as a character.

The first tale, called Sunshine Through the Rain, is a child's fable. Disregarding his mother's advice, Kurosawa's five-year-old alter ego (Toshihiko Nakano) ventures into the forest on a magical afternoon to see something he shouldn't, the secret wedding procession of the fox people.

Returning home, he learns that a terrible price must be paid for such curiosity. He sets off towards an uncertain future beneath a beautiful double rainbow.

Filmgoers not familiar with Kurosawa's concerns risk confusion. In a way, Dreams is the old master's own Amazing Stories.

Like Spielberg's short-lived 1985 television anthology series, Dreams deals in fantasy. It presents tales of ghosts, demons, living dolls and nature spirits, offering a range of images from the Edenic to the Dantesque, and attitudes of liberal hope that are almost quaintly dated.

As with the Spielberg series, the filmgoer expects rather more, given the creator's reputation. Something more daring, perhaps more amazing .

There is a touch of disappointment when, in a wonderful bit of technical trickery, Kurosawa's dream Other (Akira Terao) steps directly into Vincent Van Gogh's painting Canal Bridge and crosses it in search of the artist.

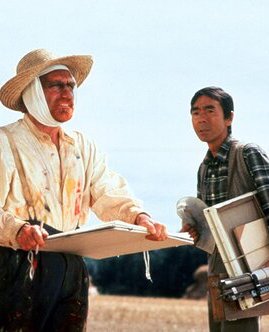

In the vignette called Crows, it turns out that Van Gogh (director Martin Scorsese in a cameo role) has no time and no wisdom for his Japanese admirer. We learn that art is no escape, while enjoying some terrific movie process work (special effects credited to George Lucas's Industrial Light & Magic studios).

To enjoy life, to appreciate beauty, to be one with nature — these are simple, even obvious messages. Like Shakespeare’s Prospero, Kurosawa has learned to value simplicity.

Contemplative rather than confrontational, Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams may be too gentle, too traditional and too calm for the Total Recall crowd. It’s worth our attention nonetheless.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1990. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Though I didn’t mention it in the above review, nuclear disaster was the subject of Akira Kurosawa’s sixth “dream,” a vignette he called Mt. Fuji in Red. In it, an atomic power plant melts down with nightmarish results. In April 2011, San Francisco high school teacher Anne Campagnet-Reed posted an essay to her online blog headlined Kurosawa Saw It Coming: Fukushima Meltdown in which she credits the director for “presciently” portraying the March 2011 meltdown of Japan’s six-reactor Daiichi facility.

Kurosawa had a profound understanding of the nuclear fears his nation lived with. He was 35, and a film director with three features to his credit in August 1945, the month that the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Ten years later, he would confront those feelings directly in the 1955 psychological drama I Live in Fear. His 16th feature, it starred Toshiro Mifune as an elderly factory owner determined to relocate his family to Brazil rather than see them die in the nuclear war he believes to be imminent. (The picture arrived in theatres 13 months after the debut of Godzilla, Japanese cinema’s most famous metaphor for the nation’s deep-seated nuclear anxieties.)

He returned to the subject in his penultimate feature, 1991’s Rhapsody in August. Set some 45 years after the war, it tells the story of a family still traumatized by the destruction of Nagasaki. The picture recalled the atomic bombings for the war crimes that they were, a subtext that many American critics refused to accept. The picture was not a success in the U.S. market. Celebrated as one of the all-time great cinema artists, Akira Kurosawa died in 1998 at the age of 88.

See also: While his film is not an actual remake, Star Wars director George Lucas acknowledges Kurosawa's 1958 picture The Hidden Fortress as a major influence on him and his 1977 sci-fi epic.