Friday, March 30, 1973

CREATING MAJOR EXCITEMENT ON the movie scene recently has been the arrival of two new films, in each case the maiden theatrical feature of a Canadian director.

One, the work of Albertan Bill Fruet, was the 1972 Canadian Film Award-winning Wedding in White. The other, directed by Vancouver-born Daryl Duke, was a U.S. production, Payday.

Both were finely acted dramas of personal tragedy, and each brought its director to Vancouver for the local premiere. In separate interviews, the two men revealed surprisingly similar backgrounds, and quite different attitudes towards the development of a feature film industry in Canada.

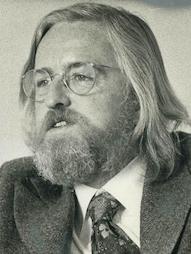

Duke, the better known of the two, is not vitally concerned with the idea of Canadian films. A commanding presence in a patriarchal beard, he speaks with an edge of tempered authority in his voice.

“The time for that super-heated kind of nationalism is past,” Duke says. “I think it might have made sense in the '50s. I don’t think it makes that much sense now."

Fruet, who is just becoming known, is passionately concerned. A 39-year-old who looks 10 years younger, his arguments are solidly economic.

''Why should we allow 800 films a year to come into this country from the United States, and a gigantic amount of capital out of here?” Fruet argues. “We're losing an awful lot of money every year. Why shouldn’t we try to retain it?”

Both men trace careers that have passed through the National Film Board, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and, eventually, the U.S. Each prefers feature-film directing, and is determined to continue making movies.

Daryl Duke started out with the NFB. In 1953, he moved into the CBC’s new Vancouver television station. A few years later, he moved to Toronto and into production for the full network.

Involved in public affairs broadcasting at a time when the CBC was building a reputation for documentary excellence, Duke soon gained a reputation for creative integrity, taste and intensity.

He worked on some of the best known shows — Close-Up, Explorations — and opened up one of his programs, Quest, to vibrant, experimental drama.

Inevitably, Duke ran afoul of an easily shocked CBC bureaucracy. “I believed in doing what I thought had to be done with a series," he says. “It’s like what Napoleon said about a bayonet: you can do anything but sit on it.”

He left Canada for the U.S. in 1964. As a freelance director, he found work in Holllywood directing The Steve Allen Show, later moving to New York where he directed The Les Crane Show, the ABC network’s first attempt to give Johnny Carson some competition.

In recent years, Duke has been an international commuter, landing in Canada to direct episodes of such series as Wojeck, Cousin and Quentin Durgens MP, landing in the U.S. to do similar series work there. He won an Emmy for The Day the Lion Died, an episode of a series called The Senator.

Most recently [1973], he has been doing made-for-TV movies, including the two-part thriller The President’s Plane Is Missing, and the as-yet-unseen Cradle of Hercules, a new Charlie Chan mystery filmed in Vancouver.

Despite all his television work, Payday, from an original screenplay by Don Carpenter, is his first theatrical feature. Set in Alabama, it's a wholly U.S. venture.

Film, Duke says, is a world in which borders don’t mean very much. “You’re in theatres asking people to pay $3 a ticket . . . that world is a much more international world (than on television).”

The only way for Canadian films to make it is to grow up in terms of international realities. The first problem is financing. “That was one of the reasons that, after I left the CBC, I knew that I would have to work in the United States.

"At the time I started out, you could be one of the most talked-about television producers in the country,” Duke says. “But then you could walk across the street and find that your name wasn’t worth a dime at the bank.

“There were a lot of properties I lost because I couldn’t buy the rights to the book or see any hope, based on a Canadian reputation at that time — this was almost 10 years ago — of getting a film off the ground and financed here.”

Even when when films do get made, though, Canadians have shown little ability in selling their product. “There must be an evolution towards maturity and wisdom in terms of marketing,” Duke says.

“There will be good Canadian films made but (their makers) will have to lose their naïveté about distribution and about casting. They’ll have to start delivering to international distributors marketable, saleable stories and stars, so that a U.S. distributor is going to want to spend maybe $600,000 or $800,000 on prints and advertising.”

Lethbridge-born Bill Fruet agrees with most of Duke’s economic arguments. Fruet went to Toronto in 1952. He intended to work as an actor, but found that he had to supplement his CBC parts with jobs as a photographer.

When the NFB set out to make its first dramatic feature, an educational Western called Drylanders [1963], Fruet landed an important supporting role. “That’s when I really fell in love with production,” he says.

“It was my first taste of a major film production, and found myself on the other end of the cameras more than I did acting. I decided to try to make my career in production.”

In 1962, Fruet left Canada for California, there to work with a number of small industrial film companies, write some television series scripts and “get some background.”

“I lived in California for three years,” Fruet recalls. “And I think the whole American way of life taught me a lot of things. I could see the opportunities back in Canada. It was just a matter of getting off your fanny and doing something.”

Fruet returned to Toronto in 1965, taking a job with the CBC as a film editor. “That’s where I met (Goin’ Down the Road director Don) Shebib," he says. "Shebib was working and getting his first directorial assignments for a public affairs show.

"We started rapping one day. I found out that he was at UCLA the same time that I was. I took an editing course (during) one summer session. He was doing his thesis there at the same time. We never met, but we were working in the same building, he at night, and I during the day."

Together, Fruet and Shebib developed the idea for Goin' Down the Road, the first English-language Canadian film to make any kind of international impact. Fruet was director Shebib’s screenwriter, a partnership they repeated on the less successful teen comedy Rip-Off (1971). Then Fruet went on his own, developing Wedding in White from his own stage play.

According to Fruet, Canada will be able to gauge her success at nation building by the success of her film industry. ''I think you adopt a certain attitude here. You can't help but do it. It's why our whole country's going, bit by bit.

“We're losing it because we haven't got the incentive to do things on our own. We just watch, constantIy.''

That attitude infuriated Fruet. “They say ‘Canadians are not speculators, they’re not investors.' And it applies to everything, too. That's why the country's going, bit by bit. We're not hanging on to it.

''It enrages me to try to be an artist in this country. A playwright? l can't get into my regional theatres. A filmmaker? I can’t get into my motion picture theatres. Where else would this be tolerated?''

One by one, Fruet ticks off the problems that have to be overcome. He is candid about the entertainment value of many domestically-made films. "Perhaps we've been had. A lot of films are too much the personal statement.

“Too many of our filmmakers are just good filmmakers — technicians — that have gone to school, or through the CBC,” he says. “Not enough of them have had any theatrical background. They know nothing about actors and theatre.

“What is film? Basically, most good movies are good theatrical movies. We go there for the same experience, right? l don't think those are the kind of films we’ve been making."

Fruet agrees with Duke that Canadians don't know how to market their own films. “Distribution in this country has never really been confronted with handling a film made here. Everything’s packaged. It comes here with the film. It's all in a little kit. They put up the displays, and that's it.”

He faults theatre owners as well as the distributors for their inertia.” We've got two major chains in this country, and it's hell to get into a theatre if you’re a little Canadian film.

“In a way, I can sympathize with them,” Fruet says. They buy packages. They buy four baddies and two goodies. The whole thing is like that. (And then) along comes a lonely little Canadian film.

“Why bother? It’s a risk no matter how good it is. (Theatre owners) don’t deal in that kind of arrangement.”

Confronted with the raw ennui of distributors and exhibitors, Fruet can see a possible legislative solution. “I hate the word 'quota,’ but (Canada) is the only country that doesn't have one.

“We’ve had a World War. We've seen Italy, France and England almost completely destroyed, and yet they've built up major film industries, as well as all their other industries.

“These countries shut their doors (to Hollywood), and said ‘our industry first, then you can bring in your pictures.’ But not here.”

Like Duke, Fruet sees the problem of financing as primary. “The Americans are patiently waiting. They would love to come in and do co-productions with the Canadian Film Development Corporation [now called Telefilm Canada]. It's the CFDC that won't co-operate with them.

"The Italians want to. The French want to. But the Canadian businessman is, as usual, so conservative. I can't find the right adjectives to describe him. He can’t see it. He's only coming into it for the big tax write-off — because he gets to write off the CFDC portion, too. The wrong reasons.

''What a hell of a way to start a business.”

Fruet, whose own first film is an artistic as well as a financial success, presents a forceful case for wholehearted investment. “The worst thing about the industry right now is that we’re not making pictures that make a lot of money.

“That has to happen, or we don’t have an industry. It's as simple as that as far as I’m concerned. Plus, it’s a good, wholesome adventure,” he adds.

''lt’s a damn good business to be in. It’s proven. I can’t understand why the Canadian businessman isn’t in it. In nothing else can so much money be made if he hits a good picture. Broadway used to be the same thing.

"You back a winner on Broadway and you were a multi-millionaire with very little investment at times. It's high risk, but it’s big money, too. Canadians have never, ever thought that way.''

Fruet's future plans are pretty well tied to Canada. Although his next project is not definitely set, he has both a television series and another stage play in the talking phase. Given his choice, though, he would like to direct another feature film, this time from somebody else's script.

Duke, shortly before the local opening of his film Payday, completed work on a U.S. television pilot called If I Had a Million, a possible anthology series not unlike Love, American Style [1969-1974]. The projected series is based on the idea of endowing its characters with a sudden million dollars and following the results.

"The pilot I did had one segment very farcical and comic, one was mildly sentimental and amusing, and one very serious," Duke said.

For the future he is considering film projects in Miami, Paris and New York. The choice is still to come but, like Fruet, his preferred line of work is movie director.

Unlike Fruet, and despite the fact that he maintains his citizenship and a house in West Vancouver, Duke won't tie himself to Canada. ''I'll work wherever the script and the story, the cast, the distribution and the whole scene come together properly.”

The above is a restored version of a Province interview feature by Michael Walsh originally published in 1973. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: While Payday marked Daryl Duke’s debut as a feature director — it opened in Vancouver three weeks before the above interview was published — his major presence remained that of a television director. The political thriller The President’s Plane Is Missing was the ABC Movie of the Week on October 23, 1973. Its cast included Payday star Rip Torn, who played the absent chief executive’s National Security Advisor. NBC broadcast If I Had a Million on New Years Eve, but decided not to turn the feature-length pilot into a series.

Not mentioned in our 1973 conversation was Duke’s made-in-B.C. I Heard the Owl Call My Name, a CBS-TV movie aired on December 18, just in time for Christmas. The story of a fatally ill Anglican priest (played by Tom Courtenay) sent to a Kwakiutl First Nations parish, it is discussed at length in Charles Campbell’s 2006 tribute to its Vancouver-born director. “It belongs in the canon of great B.C. movies,” he says. And so it does.

One Duke title we can safely exclude from that list is Cradle of Hercules, noted above as “the as-yet-unseen . . . new Charlie Chan mystery filmed in Vancouver.” Shot here in 1970, it sat on Universal Television's shelf for nearly a decade before finally being broadcast in July 1979 as The Return of Charlie Chan. The second-to-last of some 50 films featuring the Asian-American detective, it was subsequently retitled Happiness Is a Warm Clue.

Actually worth remembering is Duke’s second theatrical feature, 1978’s The Silent Partner. A caper comedy set in Toronto, it was nominated for six Canadian Film Awards. It won three, including Best Picture and Direction. His third theatrical feature, 1982’s Hard Feelings, took him to Atlanta, while the 1986 release Tai-Pan was shot on locations in Hong Kong and Guangzhou, China. Between them, he found time to direct an epic TV miniseries, The Thorn Birds, made in Hollywood and broadcast over four nights in March 1983.

It only seems appropriate that Duke’s final film, the psychological drama Fatal Memories, was shot on location in Vancouver. A TV movie, it was aired in November 1992.