Friday, May 17, 1974.

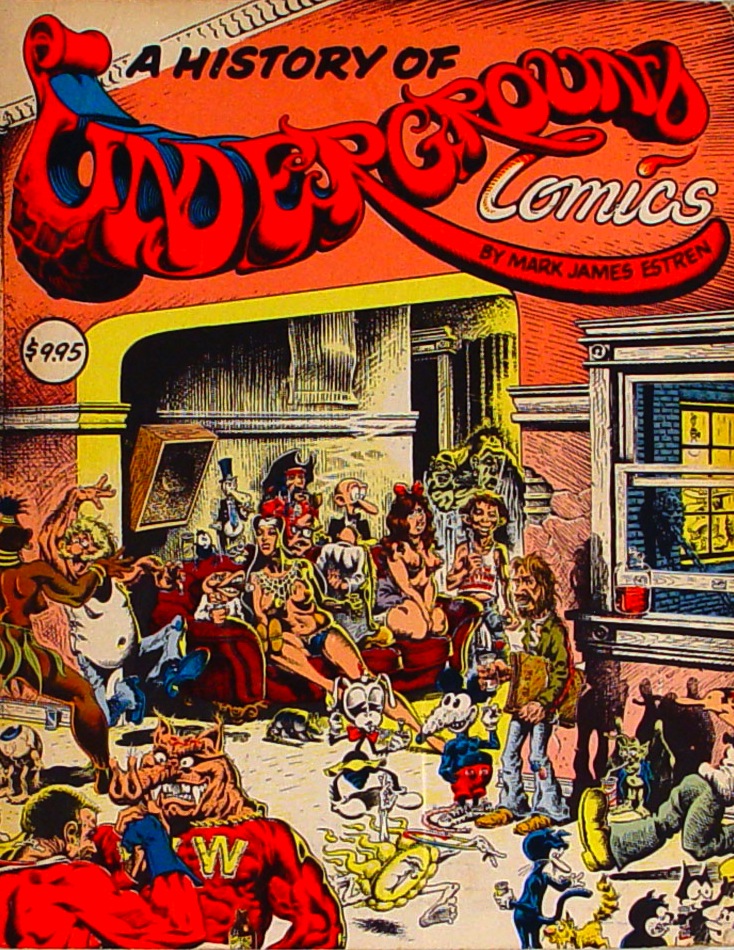

A HISTORY OF UNDERGROUND COMICS. By Mark James Estren. Straight Arrow Books, 1974. 320 pp. Illus. $9.95.

SADOMASOCHISM IN COMICS: A HISTORY OF SEX AND VIOLENCE IN COMIC BOOKS. By Hans Siden, Greenleaf Classics, 1972. 224 pp. Illus. $3.95.

COMICS: THE ART OF THE COMIC STRIP. Edited by Waiter Herdeg and David Pascal for The Graphis Press. Hurtig Publishers, 1972. 126 pp. Illus. Indexed. $16.50.

LIKE IT OR NOT, the counter-culture, one generation's colourful hope for a better future, seems to be winding down. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the once free-wheeling world of underground comics.

It is interesting, and socially significant, that mainstream comic books were part of the North American scene for more than 30 years before anyone seriously attempted to write their history.

Underground comics, with us for about six years [in 1974], have already spawned a sober, almost sombre chronicler. It is significant, and perhaps even more interesting, that the underground comics story echoes a 20-year-old tale of woe in the world of mass-distribution commercial comics.

In Vancouver, comic history has managed to repeat itself.

Comics originally came to grief here in 1948. Citizens, concerned with a growing juvenile delinquency problem, found a likely villain in the crime comics of the time. The villain, an American phenomenon, was vanquished by one E. Davie Fulton, at the time a B.C. member of the Progressive Conservative opposition in Ottawa.

Fulton submitted a private member's bill making it a criminal offence to make, print, publish, distribute, sell or possess any comic that "exclusively or substantially comprises material depicting pictorially commission of crimes real or fictional." His bill was passed.

Fourteen months ago [March, 1973], the Georgia Straight, Vancouver's oldest alternative press tabloid, was charged under those Criminal Code provisions prohibiting distribution and sale of obscene materials. Seized were some 1,300 underground comic books.

The Straight lost its case, thus making another kind of comic book illegal locally. Ironically, one of the artists currently working in the comics underground —Rand Holmes — is a Vancouverite.

Three of the current best-selling underground comic titles in the U.S. — Harold Hedd No. 1, White Lunch Comics and All-Canadian Beaver Comix — were originally produced here. A fourth best-seller, Harold Hedd No. 2, was created here, but published in the the United States.

As a result of the recent judicial decision, local booksellers may be reluctant to stock A History of Underground Comics, an oversized paperback by Mark James Estren. An attractive volume printed on quality book stock, it features cover art by the locally-based Holmes.

The title is something of a misnomer. Estren, a 25-year-old journalist, has actually turned out an extended apologia for a little-understood vehicle of self-expression and social commentary. His objectivity is destroyed by his closeness to his subject and the relatively brief time that there has been such a thing as underground comics,

In 1965, when Jules Feiffer sat down to recall The Great Comic Book Heroes, he was a mature author dealing with a mature medium. His considered opinion: "Comic books, first of all, are junk.

"To accuse them of being what they are is to make no accusation at all. Junk is there to entertain on the basest, most compromised of levels . . . (its) readers, when challenged, will say defiantly, 'I know it's junk, but I like it.'

"Which is the whole point about junk. It is there to be nothing else but liked."

Estren, like many modern commentators on the graphic arts, cannot abide the idea of loving junk. As a result, he insists that the undergrounds — all undergrounds, God help us — are Art with a capital A.

"Art," Marshall McLuhan once observed, "is anything you can get away with." Estren, who quotes McLuhan to bolster an occasional point, tries to get away with a lot. In doing so, he is guilty of some curious doublethink, and some even more curious omissions.

He chronicles the rise of the underground with breathless revolutionary rhetoric that is certain to please the special pleaders in the alternative press. He decries — often rightly — the hypocrisy of the "straight" world. He is particularly harsh in his criticism of the Disney organization, a corporation that has mercilessly sued any and all violations of its copyright.

Later, though, he cheers the unworldly underground cartoonists when they discover that they, too, can sue when the characters that they have created are used without permission. In one case, Estren perceives a corrupt system using its evil courts to suppress free expression. In the other, he sees valiant revolutionaries scoring victories for "the people."

It's all a bit schizoid, and not particularly informative. He's much better at introducing the artists and their work — although here, too, he stumbles.

Initially, he creates the impression of comprehensiveness, something that is of vital importance to anyone with a real interest in this fascinating but difficult-to-follow medium. But there are glaring omissions.

Two important subjects Estren touches on are the use of sex and violence in the comics. Although explicit only in the undergrounds, neither theme is unique to them. Nor, for that matter, are they unique to the United States, a fact brought out in Hans Siden's Greenleaf Classics survey, Sadomasochism in Comics: A History of Sex and Violence in Comic Books. A look at "those little comics that men like," his book explores what was once a real underground in America and now exists as an open commercial enterprise in Europe and Japan.

Siden is not so much concerned with artwork as he is with social perspectives. He records a phenomenon that is, he claims, as old as history. In particular, though, he wants to bring recognition to Eric Stanton [1926-1999], an American artist whose work has been sold surreptitiously since the late 1940s, and whose style is familiar to millions who have never heard his name.

Stanton's cartoon strips, featuring severe-looking female sadists, buxom and black-booted, were sold through advertisements in the back pages of pulp magazines through the 1950s and early 1960s. Recently, his distinctive style was parodied in Cowgirls at War, a full-length insert in 1973's National Lampoon's Encyclopedia of Humour. (The same book contains a parody Volkswagen advertisement that was the subject of national news coverage.)

Even readers of the relatively innocent DC and Marvel comics have seen evidence of Stanton's influence on his mainstream colleagues. It certainly has been recognized in the graphic arts world.

Stanton is even mentioned in what is perhaps the most unflinchingly erudite book to appear on the subject of comics, the sumptuous Comics: The Art of the Comic Strip.

Produced by Zurich's Graphis Press, this trilingual (English, French, German) publication is unsparing in its use of colour and rigorous in its scholarship. It is, in a word, excellent.

The project combined the talents of 10 international graphic arts experts, including Feiffer and Les Daniels (whose own book, Comix, was reviewed here last week [May 1974]. It is the best history yet produced on the specific subject of American comic books).

Originally produced as two special issues of the magazine Graphis, this volume is an expanded edition, indexed and annotated. Despite its hefty price tag ($16.50) it is exactly what the comics have needed.

It is a book with the resources and the perspective to bring together the divergent styles, traditions and themes of comic artists from formal advertising art to the underground.

It provides needed assurance to persons of normal intelligence and taste who may be embarrassed by their positive response to comic strips, books and poster art.

"Comics," according to editor David Pascal in his succinct foreword, "are a twentieth-century art . . .

"Comics have produced new mythologies daily for the baffling new, time-compressed, machined twentieth century. They have reflected in simple idiomatic terms the vast wars, new moralities and personal and social cataclysms of a new age with new dynamics.

"Even within the comics framework, those comic books that pictured emasculated literary classics never sold well. Comic art produces its own myths and heroes. Just as other arts, these change with their times.

"The contents found in the front pages of a newspaper differ little from the imagined words and images to be found distilled in the back pages where the comic strips are.

"The paper is real. The strip is art."

Today, as the counter-culture is being absorbed into the totality of the North American experience, its ideas and attitudes are not lost. Instead, they contribute to the new shape of the whole.

Among its more important contributions is the idea that the comics, if not capital-A Art, are an important medium of communication and positive expression.

The Georgia Straight may have lost its case. The comics, however, have already won their point.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1974. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In the early 1970s, the time when these three books (and the above review) were written, the battles were still being fought. Though a previous generation's cultural critics, a group that included Marshall McLuhan and Gilbert Seldes, had earlier pronounced upon the artistic value of newspaper comic strips, comic books remained on the margins. Their growth as a medium of social expression had been stunted by the post-Second World War crusade against crime and horror comics that resulted in the 1954 Comics Code Authority in the U.S.

Deliberately infantilized, mainstream comic books remained "kid's stuff" for more than a generation. Available on supermarket spinner racks, their pages were filled with Disney (and Disney-like) funny animals and increasingly ridiculous superheroes. Then, toward the end of the rebellious 1960s, something called "underground comix" showed up in the inner city "head shops" that were part of the counter culture's sex-drugs-rock'n'roll revolution. Although the underground era was relatively short-lived, it resulted in the emergence of alternative and independent comic publishing enterprises, as well as a creators' rights movement.

In the 40 years since, the history of comic books has been a complex, often wondrous story. It includes the emergence of dedicated comic shops, graphic novels, celebrity artists and comic book studies in our universities. In the early 1990s, mainstream publishers DC and Marvel set up "mature" publishing divisions to bypass the Comics Code; then, rather belatedly, abandoned it entirely (Marvel in 2001; DC in 2011). Today, major comics-inspired movie and television franchises dominate the popular culture. And events such as the Vancouver Comic Arts Festival make it all both local and authentic.