Friday, August 27, 1971

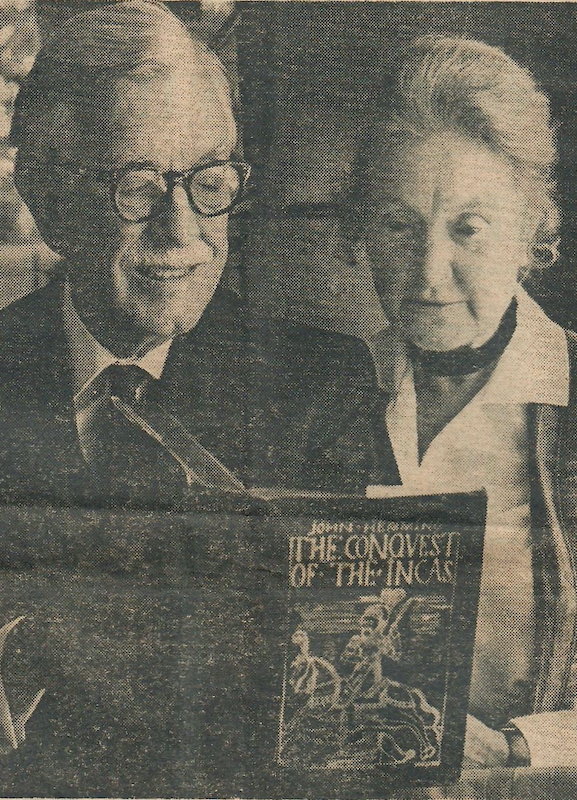

FOR JOHN HEMMING, VANCOUVER-BORN author of the recent [1971] publishing success The Conquest of the Incas, Shakespeare is more than a great playwright — he is a fondly remembered family friend.

It was to "my fellows John Heminge, Richard Burbage and Henry Condell" that the playwright willed sums of 26 shillings, eight pence apiece for the purchase of memorial rings.

"In those days, men did not wear ties," explained Harold Hemming, the contemporary author's father, "so they could not show that they were in mourning by wearing a black tie. Instead they wore mourning rings. My family's ring was lost when my grandfather's house burned down in Quebec City in the 1850s."

Hemming, with his wife Alice, has been spending August in West Vancouver. The Hemmings, who met and married here in the 1930s, are stopping over on their way to South America where they will join their son John.

Both were excited to learn about the World Shakespeare Congress, held this past week [August, 1971] on the Simon Fraser and University of B.C. campuses. Glancing over the congress program, Hemming recognized several friends and associates among the delegates.

The Hemmings, a Canadian family with their business address in London, have managed to maintain close ties with their "olde friend" Shakespeare.

"The Regents Park open air theatre is just behind our house,” said Mrs. Hemming. In addition to the productions mounted just beyond their doorstep, they also enjoy following the season at Stratford.

If Hemming takes a special pleasure in the Bard's work, he does so with good reason. It is to his ancestor, the Elizabethan John Heminge, that all modern Shakespeareans owe their thanks.

Together with Henry Condell, Heminge was responsible for assembling the works that made up the priceless Shakespeare First Folio.

Heminge, along with Condell and Burbage, was an actor, a leading member of the company whose patron was Henry, Lord Hunsdon, Queen Elizabeth's Lord Chamberlain.

In the spring of 1594, the Lord Chamberlain's Men welcomed into their midst the 30-year-old William Shakespeare. At the time, the company was working out of The Theatre, the first building constructed in England for the purpose of staging plays.

The Theatre had been the brainchild of actor Burbage's farsighted father James, and it had risen just 18 years earlier on a plot of leased land. When Shakespeare joined the company, the lease was nearly up, but the elder Burbage was busy with another bright idea.

He had acquired a former Blackfriars' monastery and, by 1596, had completed the refurbishing necessary to open the kingdom's first indoor public theatre. Unfortunately, his neighbours were not amused.

The local citizens, including the same Lord Hunsdon that sponsored his son's troupe, petitioned the Privy Council to forbid such goings-on in their district. Blackfriars remained dark.

Shortly after, James Burbage died. His holdings passed into the hands of his sons but, Elizabethan theatre groups being the tight little social groups that they were, they were soon divided among the company's principal players.

The division came about in 1598, the year that The Theatre's lease expired. When lengthy negotiations failed to secure a renewal, ownership of the company's physical assets was turned over to seven shareholders, among whom were the Burbage brothers, Richard and Cuthbert, Shakespeare, Condell and Heminge. The Theatre was torn down to rise again on the Thames's south shore, renamed The Globe.

Heminge, the rotund, asthmatic actor who shared the stage with Shakespeare and Burbage, proved to have a more solid business sense than either of them. Within a year, he had become the company's sole business manager.

The esteem in which he was held by his fellows is a matter of public record. Heminge was the man they entrusted with the care of their orphans and estates. At one time, he acted as the agent of all the London performing companies in negotiations with the King's Master of the Revels.

The record recalls neither a complaint nor a lawsuit ever having been entered against him. Heminge was a man who could be counted upon to set things right. The subsequent death of Burbage, in 1619, prompted one poet to pen a quatrain containing the lines:

Then fear not, Burbage / heaven's angry rod

When thy fellows are angels / and old Heminge is God.

There were, however, to be many years of success and camaraderie before eulogies would be in order. In 1604, the Elizabethan age ended. James I ascended the throne and the Lord Chamberlain's men acquired an even more prestigious patron.

The King's Men became official members of the royal household, and were given the right to wear the king's own livery. Like Burbage and Shakespeare, Heminge was now classified as a gentleman and was granted his own coat of arms.

In 1608, Burbage saw a chance to realize his father's dream for a Blackfriars theatre. Again his leading associates in the acting company were called upon to become partners in the venture.

The indoor theatre became the winter home for the King's Men and, in 1613, when The Globe burned to the ground, it proved a most welcome asset to its owners,

By 1620, it was all over but the memories. Shakespeare and Burbage were dead. Heminge, who had acquired the playwright's theatrical holdings, had become the dean of London actors. He and Condell were the last surviving members of the original company.

The two aging actors decided it was time to give Shakespeare to the world. And printer William Jaggard couldn't have agreed more.

Jaggard, Printer to the City of London, was well aware of the drawing power of Shakespeare's name. The year Burbage died, he had published Thomas Pavier's quarto of pirated editions and corrupted texts. The opportunity of publishing the true texts made him willing to risk the expense of a full folio edition.

In 1623, the First Folio, a collection of 36 plays, came off Jaggard's press. A total of 500 copies of nearly 1,000 pages each went on sale in London. Said Heminge and Condell in their introduction, “To the Great Variety of Readers:

" . . . it is not our province, who only gather his works, and give them you, to praise him. It is yours that reade him. And there we hope, to your divers capacities, you will finde enough, both to draw, and hold you; for his wit can no more lie hid, then it could be lost. Reade him, therefore; and againe and againe."

Their action was timely. A few years later, Oliver Cromwell, England's self-proclaimed Lord Protector, would execute a king and give Englishmen not what they wanted but "what was good for them."

Under the sombre Puritan, the theatres would be closed and the offensive manuscripts destroyed. Fortunately, the Folios survived.

And, perhaps not surprisingly, printer's ink managed to survive in the Hemming line. Toronto-born Harold Hemming is chairman of Britain's Municipal Journal Group of Companies, publishers of civic periodicals.

His wife, Alice, at one time a Vancouver newspaperwoman and radio personality, is his editorial director.

The Hemmings take a good deal of parental pride in their son John. A graduate of Vancouver's St. George's College and Montreal's McGill, he has already been a success twice over.

As a businessman, he headed up a dynamic British-based firm dealing in the organization of trade exhibitions. In his spare time, he researched and wrote a prize-winning book, The Conquest of the Incas.

Not only was the book well received by scholars and critics, but it also sold well. Last year, Hemming was awarded the £1,000 ($2,500) Robert Pitman Literary Prize for a first book. Currently he is in Latin America working full time on a second, the story of Brazil's Indian Protection Service.

The family takes another kind of pride in their generous ancestor. Of Heminge and Condell, Harold Hemming says:

"If these two gentlemen had not produced the First Folio, it is quite possible that today we would not know anything about many of Shakespeare's works, so they can be looked on as great benefactors to the whole world.”

Their work was done, said the editors Heminge and Condell in their own dedication to the First Folio, "without ambition either of self-profit or fame; onely to keepe the memory of so worthy a Friend, & Fellow alive, as was our Shakespeare . . . "

The above is a restored version of a Province Showcase Magazine feature by Michael Walsh originally published in 1971. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: The serendipitous visit to Vancouver of an elderly couple — in 1971 Harold Hemming was 78; his wife Alice was 64 — with a blood connection to Shakespeare’s friend and fellow John Heminge gave me the opportunity to tell the story of the Bard’s acting company and the origins of the First Folio. It linked perfectly with my coverage of the then-ongoing World Shakespeare Congress.

Under other circumstances, an interview with Mr. and Mrs. Hemming might have focused on the story of two accomplished individuals who met in Vancouver. The year was 1930. London-born, Alice Weaver had grown up on a B.C. farm. A University of B.C. graduate, she was the Province reporter who interviewed Canadian-born First World War hero Henry Hemming when he arrived in Vancouver with a delegation of British headmasters visiting universities in Canada. They married a year later in London.

Their story, highlighted in Alice’s 1994 obituary in London’s Independent newspaper, is a fascinating tale. Their son John was born in Vancouver in 1935 because, as we learn from his Wikipedia entry, his father “foresaw” the coming of the Second World War and wanted him to have Canadian citizenship. Alice returned to B.C. in 1940, where she wrote “two regular columns [a week] in the Vancouver Province and . . . daily broadcasts on her own radio show in support of the War effort.” Widowed in 1976, she continued to be an influential leader in the international women’s movement until her own death in 1994. There’s so much more to the Hemming’s story than I can squeeze into this brief space. I like to think that somewhere out there someone is working on an full biography of this remarkable couple.

Congressional record: Reeling Back’s WSC archive consists of a Preview feature followed by my Opening report, a Tuesday report, a Wednesday report, a Thursday report, a Friday report, a First Folio feature about a family with links to both Shakespeare and Vancouver, a Saturday report, a Closing report, and my Summary feature.