Monday, August 30. 1971.

IN EIGHT DAYS OF brilliant papers, exciting panels and varied entertainments, delegates to the first World Shakespeare Congress have been moved to offer standing ovations on only three occasions.

The first was for the University of British Columbia's Roy Daniells, whose keynote address to the opening banquet was written and delivered in rhyming couplets. A second was offered at the closing ceremonies for Simon Fraser's Rudolph Habenicht, who conceived and carried through with the idea of the Congress and served as its director.

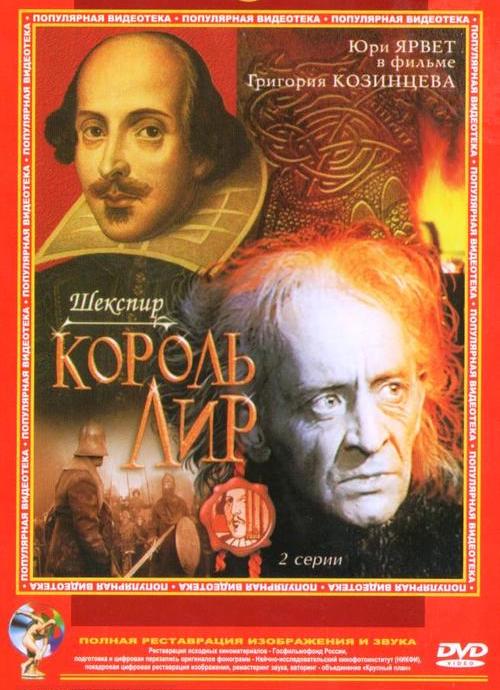

The most prolonged, however, went to Soviet filmmaker Grigori Kozintsev, whose adaptation of King Lear was privately screened for Congress members Saturday morning [August 28, 1971] at the Varsity theatre. Following the showing, the film's first in North America, Kozintsev was carried up the aisle on a flood of handshakes, enthusiasm and applause.

His Lear, like his Hamlet [1964] and before that, his Don Quixote [1957], was a film of rare power and intensity. It took hold of its premiere audience from the first moment, gripped them for more than two hours and finally lifted them from their seats to pay tribute.

Kozintsev is a superb craftsman. He is a screen tactician whose strategies are mapped with mathematical precision and executed with lean, hard-edged style.

Lear begins and ends with landscape. The first scene, played out in silence, finds the poor, the lame and the crippled making their way along a barren road. They've come in their hundreds, gathering beneath the battlements of Lear's castle, to hear his proclamation dividing the kingdom.

The people are solemn and apprehensive; Lear’s knights, darkly helmed and threatening. Before a single line has been spoken Kozintsev makes it clear that this day will come to no good.

His concluding scene involves the people again. This time, ravaged by the wars that have passed over them and surrounded by the debris of battle, they are silently, stolidly rebuilding.

His script, "after the play by William Shakespeare," is a rendering rather than a translation. The object of screen adaptation, he told Congress members Friday [Aug. 27, 1971], is to preserve not the text, but the metaphor.

On screen, Kozintsev describes Lear's decline into madness in strikingly visual terms. Lear, the all-powerful king assembling his 100 knights, looms regally over the audience, viewed by a camera on its knees before his majesty.

Lear the father-once-rejected quitting Goneril’s palace, suddenly has a more normal stature as the camera rises to view him straight on. Lear, the man-made-mad raving against the storm, is a small, pathetic creature examined from a god's-eye view.

In a similar way major themes find themselves expressed in recurring screen images. Lear receives his daughter's declaration of love seated beside a roaring hearth fire. Later, during his confrontation with Goneril, her hearth contains only smoking embers.

When he rushes in crazed flight from Regan's palace, the camera follows him across a baked and blackened landscape, one that is as cold and broken as a burnt log. The image, moving along with the speed of the story, becomes complete.

Kozintsev's style is classically direct. Absent are the ploys and gimmicks — the blurred edges, the multiple printing, flashes forward and back, changes in film speed or colour — so frequently used to make films "artistic."

Lear, like his Hamlet, was deliberately shot in black and white. The photography and set design are both starkly realistic. Gimmicks would only impede the incredible pace of a film in which not a single shot is unnecessary.

From his cast, many of them chosen for what Kozintsev calls their "country faces," he draws solid, understated performances. His Lear, Estonian actor Yuri Yarvet, has more in common with Coast Salish actor Dan George than any of the recent English-language Lears.

Except for the Shostakovich score, which blares too heroic too often, every facet of the film serves its overall feeling of elemental power.

The irresistibility of that feeling, generated by the sweep of a veteran director's entire composition, carried the Congress delegates the entire distance.

In the moment of reconciliation between Lear and his beloved Cordelia, the tears and choked sobs of the audience played counterpoint to the sublime happiness on screen.

* * *

AS THE CURTAIN STOOD ready to fall on the last act of the World Shakespeare Congress, delegates set in motion the machinery necessary to preserve and extend the progressive, co-operative vision of their assembly.By unanimous consent of Saturday [Aug. 28, 1971] afternoon's plenary session, the Congress approved the establishment of an International Shakespeare Association, and elected a three-man committee to work for its foundation.

Birmingham University's John Russell Brown, chairman of the Investigative Committee on International Co-operation which proposed the new association in its report, will head the continuing committee.

Elected to assist him were George Hibbard of Ontario's University of Waterloo and O.B. Hardison, Jr. of Washington, D.C.'s Folger Shakespearean Library. Among the tasks proposed for the new association is the provision of an international advisory committee to act as consultants for future World Shakespeare Congresses.

Their work done, the delegates who had assembled from 30 nations readily agreed with Martin Lehnert of East Berlin's Humboldt University that their gathering has indeed been "an eloquent event of peace in action." Speaking at Saturday evening's closing ceremonies, Lehnert called the congress "an event none of us will ever forget."

The University of Toronto's Clifford Leech said that he had been deeply moved by "the general atmosphere of friendship in the congress," and cited again "the vision of Rudie Habenicht."

The converted all rose to their feet to offer Habenicht a standing ovation as he stepped to the microphone to close the congress. "We must not stop here," he said, endorsing the move to set up an international organization. "Let us all try to get together again."

As he concluded his address, the folding wall of the Totem Park Centre Lounge began to roll back along Its track, doubling the size of the hall and revealing tables groaning under the weight of a final, medieval banquet.

The first World Shakespeare Congress was dead. The marriage with an International Shakespeare Association was about to be made. It was as Hamlet said: "Thrift, thrift, Horatio! The funeral bak'd meats / Did coldly furnish forth the marriage tables."

The above is a restored version of a Province report by Michael Walsh originally published in 1971. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Ouch! Fifty-one years later, I’m still embarrassed by those final two paragraphs, the clunky conclusion to my coverage of the first World Shakespeare Congress. Yes, I’d been working for eight straight days, but that’s no excuse for using a dark quote from Hamlet to catch the mood of an entirely positive moment, one that had the hoped-for result.

The work of the three-man committee mentioned above led to the foundation in 1974 of the International Shakespeare Association. It was the organizing body of the 1976 World Shakespeare Congress (WSC) held in Washington, D.C. as part of the U.S. bicentennial celebrations. Headquartered in Stratford-upon-Avon’s Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, the ISA takes as its core mission the organization of a WSC once every five years. The most recent edition, the 11th, was held online from the National University of Singapore over seven days in July, 2021. The next gathering is scheduled for 2026 in Verona, Italy.

I’m not at all embarrassed about my review of Grigori Kozintsev’s film adaptation of Korol Lir, a piece that appeared as a separate item on the same page as my report on the Congress’s closing ceremonies. As the picture was not officially released in the U.S. until November 1972 (when it was screened at the Chicago International Film Festival), I’m going to claim bragging rights for publishing its first North American review. The fillm didn’t make it back to Vancouver until July, 1981. Back in the Varsity Theatre, I took a second look at the picture and wrote a second notice. Spoiler alert: My 1981 review is longer, more detailed, but every bit as positive as the one above.

Congressional record: Reeling Back’s WSC archive consists of a Preview feature followed by my Opening report, a Tuesday report, a Wednesday report, a Thursday report, a Friday report, a First Folio feature about a family with links to both Shakespeare and Vancouver, a Saturday report, a Closing report, and my Summary feature.