Wednesday, April 11, 1990.

CRAZY PEOPLE. Written by Mitch Markowitz. Music by Cliff Eidelman. Directed by Tony Bill and Barry L. Young. Running time: 91 minutes. Rated Mature with the B.C. Classifier’s warning "some very coarse and suggestive language and swearing."

I WAS GOING TO recommend that you read the cover story in this month's Atlantic Magazine [April, 1990]. The work of Johns Hopkins media studies professor Mark Crispin Miller, it's called "Hollywood: The Ad."

Something of a jeremiad, Miller's eye-opening essay details the transformation of the American movie business into a branch plant of the advertising industry.

Since the single-minded mission of advertising — "sell, sell, SELL" — is different from, and often opposed to, the variegated purposes of an art form like film, such a transformation can't be anything but bad news.

I was going to suggest that, in pursuit of his point, Miller goes a little overboard and overstates his case. Then I saw Crazy People.

A case study offering point-by-point corroboration of his dire thesis, this is a picture that turns Miller's Atlantic article into must reading for anyone interested in what the current crop of Beverly Hills coke-heads are really up to.

Made with utter contempt for its audience, Crazy People contains more fully developed commercial spots (directed by Barry L. Young) than an hour of prime-time television. It would justify them, I suppose, with the lame claim that it's a picture about advertising.

As written by Mitch (Good Morning Vietnam) Markowitz, it's the unoriginal story of a Madison Avenue copywriter who can no longer go with the program. "Let's face it," Emory Leeson (Dudley Moore) says to his partner Stephen Bachman (Paul Reiser), "you and I lie for a living."

Obviously out of his mind, Leeson is bundled off to the Bennington Sanitarium, a country-club asylum providing luxury accommodations for rich, sweetly harmless reality-dodgers.

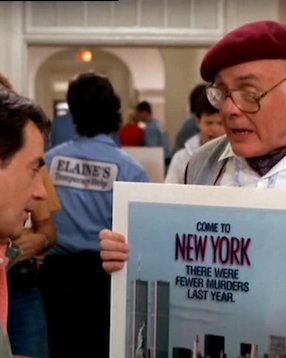

Before going, though, the little nut prepared a series of "honest" ad campaigns for some of his boss's biggest clients. By accident, they're published and, of course, they're wildly successful.

This is not a new idea.

Lampooning the ad biz has been a movie staple since the 1950s. As recently as last November [1989], there was the British-made How to Get Ahead in Advertising, the story of a London copywriter suddenly addicted to the truth.

The difference is that Crazy People is itself a nakedly direct sales vehicle. Its mocking tone is nothing more than camouflage, cynically adopted so that it can pass as an entertainment feature.

Leeson's supposedly outrageous ad campaigns are for real goods and services, a sponsor line-up that includes at least two automobile manufacturers, three travel destinations, two patent medicines, an airline, a breakfast cereal, a deodorant, an insurance company, a communications corporation, a parcel delivery service, a film distributor and a consumer electronics manufacturer.

"This honesty," says Bachman, "it's a terrific concept. We don't know much about it."

For starters, Steve, let's come clean about the fact that real corporations pay filmmakers real money to "place" their products on the big screen.

Being gently satirized in a feel-good romantic comedy qualifies as goodwill advertising. What a fun bunch of guys!

As for Tony Bill's pat little comedy, it's just so much packaging. Inconsequential filler — Leeson's loony bin-mates turn out to have a natural talent for "honest" ad concepts — it offers little substance and has minimal entertainment value.

Restricted in the U. S. (because of its fondness for Eddie Murphy's favourite f-word), Crazy People is rated Mature in B.C. with the warning "some very coarse and suggestive language and swearing."

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1990. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Among the subjects worth further academic study is the point at which ad men eased into feature filmmaking’s directorial chairs, and just what that shift of control meant to the content of the resulting movies. Although Crazy People director Tony Bill’s career arc was old school — an actor in the 1960s, he moved into producing in 1973 (The Sting) and directing in 1989 (My Bodyguard) — he eventually added commercial directing to his resume. His story, while interesting, remains something of a footnote to that of the Scott brothers, Ridley and Tony, a pair of English admen with an outsized influence on the movies of their day.

Ridley Scott, the elder of the two, is best known for his American film debut, 1979’s Alien. Despite his personal preference for past times — 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992), Gladiator (2000), Robin Hood (2010), Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014) — he keeps tinkering with his science fiction best-sellers, the Alien franchise and seemingly unending “director’s cuts” of 1982’s Blade Runner.

Tony Scott worked for RSA, his big brother’s TV commercial production outfit, for about 15 years before making his own U.S. feature debut. The result was a 110-minute ad for naval aviation, 1986’s Top Gun. Credited with changing the image of the American military in the post-Vietnam War era, it promoted a Pentagon-approved narrative and actually boosted recruitment. In 2011, the Washington Post opined that it “was the template for a new Military-Entertainment Complex.”

At least two other admen-turned-directors deserve a chapter in our proposed study. Propaganda Films alumnus Michael Bay warmed Establishment hearts with his 2001 version of the Pearl Harbor story. His reward seems to have been an open-ended contract to direct toy commercials, otherwise known as the Transformers franchise (the first five of the seven films to date). Also worth noting is Zack Snyder, who turned his ad-making talents to the production of epic comic-book movies. I mean, why engage with reality when you can focus on differences between 2017’s Justice League and Zack Snyder’s Justice League (2021)?