Monday, April 5, 1976.

W.C. FIELDS AND ME. Written by Bob Merrill, based on the book by Carlotta Monti (with Cy Rice). Music by Henry Mancini. Directed by Arthur Hiller. Running time: 111 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: some coarse language.

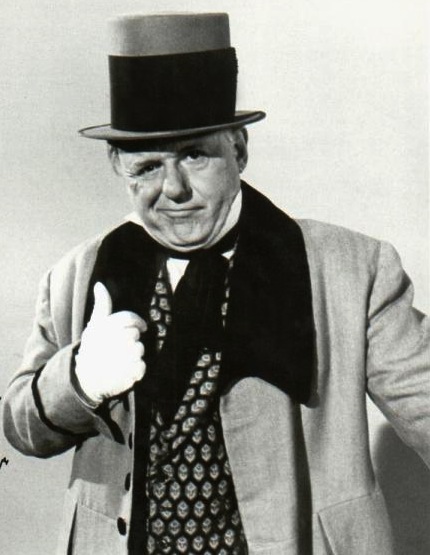

THE SILHOUETTE ON THE POSTER is unmistakable. It is top-hatted and bulbous-nosed, a painting that slowly dissolves into the figure of the man himself. In a nasal drawl, he puts forth the case for the American alcoholic.

As the camera pulls up and back, the man's voice fades into the background. Over his image a woman's voice is heard: "I was W.C. Fields's mistress for many years and, though I hoped for more, it never changed."

Fans of the late comedian might have hoped for more, too. For them, W.C. Fields and Me, the first screen biography of a misanthropic American institution, will be a disappointment. It is a film that vulgarizes his humour and reduces his life to a simplistic absurdity.

W.C. Fields and Me is the second Hollywood nostalgia epic to be released by Universal studios this year. The first, Gable and Lombard, was both more satisfying and more fun. In both cases the producers faced the same set of traps.

Sidney Furie, director of the earlier film, managed to avoid them. Arthur Hiller, in charge of the Fields project, was tripped up by them all.

The first problem is one of approach. How seriously should a movie take motion picture legends? Not seriously at all, Furie decided. Thus, his Gable and Lombard became the sort of light comedy-romance that the two pre-war superstars might have starred in during the 1930s. It was fun, rather than factual.

Hiller chose a tougher approach. His opening is borrowed whole from Bob Fosse's Lenny (1974), a film that begins with Lenny Bruce (Dustin Hoffman) in performance, followed by the voice of his former wife (played by Valerie Perrine) recalling their life together.

The echo is unmistakable. Hiller's movie, based on the book by Fields's longtime mistress Carlotta Monti, not only opens in the same way, but features the same Perrine doing the voice-over narration. She plays Monti.

The second problem is one of memory. Is it possible for contemporary actors to effectively recreate famous performances from the past? More to the point, is it wise?

Furie thought not. Neither of his stars, James Brolin and Jill Clayburgh, is seen actually playing a role that was originally created by Gable or Lombard. Direct comparisons between original and simulation are impossible.

Fosse was not particularly worried. He knew that his star, Hoffman, was a better actor than the late Lenny Bruce. Besides, relatively few people had ever seen the comedian, a nightclub personality, perform.

Hiller, who is originally from Edmonton, should have followed the example of Furie, a fellow Canadian. His star, Rod Steiger, is a fine actor, but Fields himself was no minor leaguer. As hard as he tries — and it is a most impressive try — Steiger is never more than an imitation, an overdone drawl drifting up past an obviously rubber nose.

In adapting Monti's book, screenwriter Bob Merrill seems out to prove that in Fields's case, the image was the man. There are momentary flashes of the poignant story that might have been: at one point Fields swats a dog on the street. "Still carry the scent of a hobo," he muses to himself. "Dogs smell it every time." Overall, though, his ideas are shockingly shallow.

Moments of real insight are rare. His storyline concentrates on loosely connected moments of lead-footed sentimentality: Fields shows affection for a dwarf named Ludwig (Billy Barty); of sour cynicism: Fields "borrows" the embalmed body of his buddy John Barrymore (Jack Cassidy) from the undertaker so that Barrymore can host his own wake; and dyspeptic micturation.

For the most part, Hiller seems content with this sort of nonsense, even though it reduces his film to the story of a mean-tempered drunk. Factually, it doesn't play.

The real Fields was not only an actor, but a successful writer and an accomplished juggler. He was nearly 70 when he died, so, even if it was the demon rum that finally took him, it had a good long wait.

Quick-witted for as long as he lived, his story contains a wealth of one-liners and funny incidents. Many of them have found their way into Hiller's film. Unfortunately, his object is to produce a tragedy, with the result that W.C. Fields and Me is tragically bungled.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1976. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Learning his craft during the golden age of television drama, Edmonton-born Arthur Hiller became a versatile Hollywood director. Among his best-known works are 1964's The Americanization of Emily, 1970's Love Story and the musical Man of La Mancha (1972). He became a specialist in comedy. In 1976, he visited Calgary and Toronto for the filming of the railroad feature Silver Streak. He finally made it to Vancouver in 1996, where he directed Carpool.