Wednesday, August 23, 1978

EL ESPIRITU DE LA COLMENA (The Spirit of the Beehive). Written by Francisco J. Querejeta. Music by Luis de Pablo. Directed by Victor Erice. Running time: 98 minutes. Mature entertainment. In Spanish with English subtitles.

FILM DISTRIBUTION IN FASCIST Spain was slow. This is the single thing that comes through clearly in El Espiritu de la Colmena, the murky, mournful Spanish-language drama currently [1978] on view at the Varsity Festival of International films.

The picture opens in a small Castilian town, circa 1940. The civil war is over. Life goes on.

Slowly. One day, an itinerant projectionist enlivens things somewhat by bringing a “new” movie to the town hall.

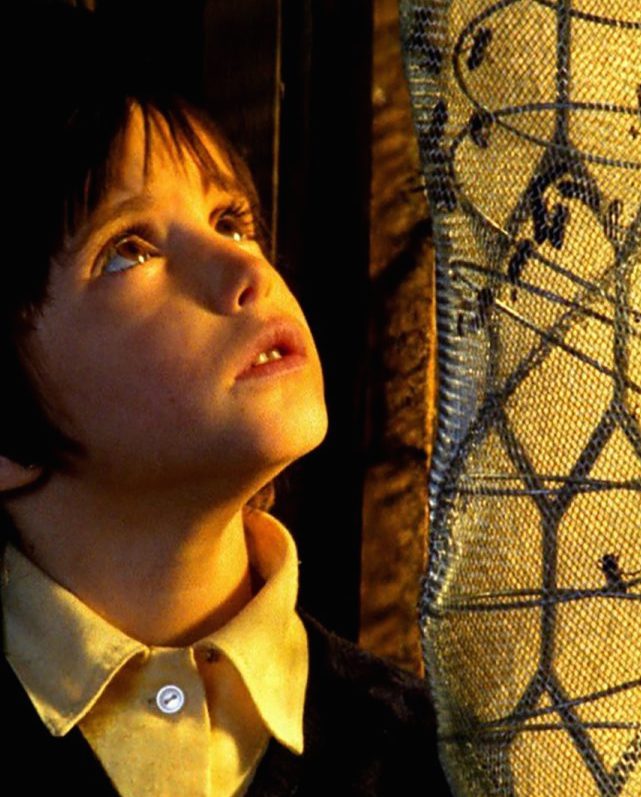

It is James Whale's 1931 American horror classic Frankenstein, the one with Boris Karloff. In the audience are the children of the local beekeeper Fernando (Fernando Fernán Gómez), eight-year-old Ana (Ana Torrent, the dark-eyed child last seen locally in Cria!), and her slightly older sister Isabel (Isabel Telleria).

Karloff's portrayal of The Monster fascinates the kids, especially Ana. They spend the rest of the film creating a personal religion in which the spirit of Victor Frankenstein's patchwork creation walks with them.

Their parents, the studious Fernando and his distracted wife Teresa (Teresa Gimpera) are preoccupied with more pedestrian matters. They fail to notice the mystical mood that descends upon their nursery.

Made five years ago [1973], director Victor Erice's picture uses the children and their monster-god to symbolize Spain under the dictator Francisco Franco, and the soul-destroying effects of his fascist rule. It is the sort of picture in which the characters spend a lot of time staring off into space.

As if to belie the old “sunny Spain” cliché, Erice has created a film as dark and dismal as an inquisitor’s dungeon. Though shot in Eastmancolor, El Espirtu de la Colmena will be remembered as a bleak-and-white picture.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1978. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: A career officer in the Spanish army, General Francisco Franco took the title El Caudillo (or The Leader) in 1936. He fought on the Nationalist side of his nation’s civil war (1936-1939), a proxy conflict that pitted monarchist forces, supported by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, against republican socialists, supported by the Soviet Union and leftist volunteers from such liberal democracies as England, Canada and the U.S. As Tom Lehrer reminds us in his 1965 mock ballad The Folksong Army: “Remember the war against Franco? / That's the kind where each of us belongs. / Though he may have won all the battles, / We had all the good songs.”

Franco ruled Spain as its military dictator from 1939 until his death in 1975. Despite his debt of gratitude to the Axis powers, his nation sat out the Second World War. Though isolated for a time following its end, his history of anti-Communism served Franco well in the Cold War years, and in 1953 the United States established a permanent military base in Spain. He resigned as Prime Minister (but not Caudillo) in 1973, the same year the The Spirit of the Beehive was released.

Celebrated by art film fans as one of the greatest accomplishments of Spanish cinema, Victor Erice’s feature marked both the beginning and the end of a transitional moment in modern Iberian culture. Although domestic political censorship remained in force throughout the Franco years, Spain opened for business in the early 1960s as a location for international movie epics, with such features as1961’s King of Kings, Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Doctor Zhivago (1965) providing work for local artisans. It also gave birth to new generation of creators who grew up harbouring ideas unacceptable under Franco, but hopeful that times would change.

And they did in the mid-1970s, releasing a new spirit perhaps best represented by bad-boy director Pedro Almodóvar’s bracingly irreverent social comedies. As my lukewarm review of The Spirit of the Beehive suggests, I just didn’t see it coming.

Celebrated by art film fans as one of the greatest accomplishments of Spanish cinema, Victor Erice’s feature marked both the beginning and the end of a transitional moment in modern Iberian culture. Although domestic political censorship remained in force throughout the Franco years, Spain opened for business in the early 1960s as a location for international movie epics, with such features as1961’s King of Kings, Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Doctor Zhivago (1965) providing work for local artisans. It also gave birth to new generation of creators who grew up harbouring ideas unacceptable under Franco, but hopeful that times would change.

And they did in the mid-1970s, releasing a new spirit perhaps best represented by bad-boy director Pedro Almodóvar’s bracingly irreverent social comedies. As my lukewarm review of The Spirit of the Beehive suggests, I just didn’t see it coming.