Wednesday, November 22, 1972.

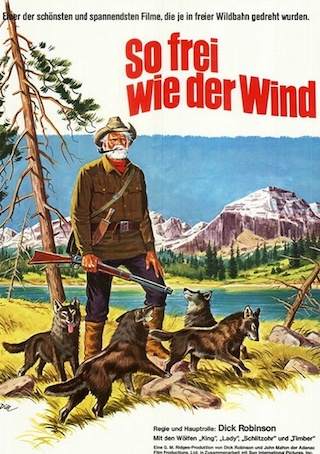

BROTHER OF THE WIND. Written by John Champion and John Mahon. Music by Gene Kauer and Douglas Lackey. Animal handling and direction by Dick Robinson. Running time: 88 minutes. Rated General entertainment.

A LOW-KEY PRESENCE ON neighbourhood theatre screens this week is Brother of the Wind, an independently-made nature film shot in the Alberta Rockies.

Its story, and therefore its dramatic impact, is slight. Sam Monroe (Dick Robinson), a widowed woodsman, sees a mother wolf shot by airborne hunters. He adopts her four cubs and raises them to mature wolfhood. Along the way, nature photographer Robinson offers a cinema scrapbook of wildlife in the foothills during two years of seasonal changes.

Originally devised by Robinson and writer John Mahon, the story outline was written for Robinson’s own Calgary-based Adanac Productions. Final editing and scriptwriting was done in Hollywood by Sun International Productions, with scenarist John Champion providing the words for narrator Leon Ames.

The result is a story with some mysterious loose ends. The most striking example is a sequence about an hour into the picture in which a hand is seen composing a letter to “Dear Dad.”

Two quick shots of a little girl with a rabbit, and an older boy with a dog, establish that the old woodsman has given pets to his grandchildren. In a letter, signed “Cathy,” his daughter implores him to come home.

Up to this point in the film, there has been little mention of family. Afterwards, they’re not seen again. The audience never finds out what happened to Cathy’s letter.

Storytelling, of course, is not the purpose of films like Brother of the Wind. The idea is to pick up the city dweller and take him for a leisurely walk in the woods, a place where he can see other creatures living free and breathing clean air, all beneath a moon so big that it seems to fill the sky.

The wolves are the main point of interest. Monroe begins by scooping them up, swagman like, into his tucker bag. The natural leader he names Sunkleep; the others are called Shy Lady, Fire Eyes and Timber. Not that it matters, though. The only one who can tell them apart is the woodsman himself.

As they grow, they encounter other animals, and Monroe encourages them to follow their instincts. He’s like a proud father when the pack makes its first kill.

“Yup,” actor Ames's voice-over admits. “What they’ve done is downright primitive and savage. But that’s nature’s way — survival of the fittest.”

Killing is not emphasized. If Robinson’s camera dwelt on the mechanics of death in the wild, that footage did not survive into the final print. A family-oriented movie, the major suspense in the first half of the film is whether or not an engaging little raccoon will lose his grip on a log and fall into a lake.

Though not exactly the sort of thing to bring out the slam-bang action fans, Brother of the Wind manages to be pleasant and folksy without being either offensive or dishonest.

◼︎ ◼︎ ◼︎

MORE INTERESTING THAN THE film itself is the story of how a low-budget feature is currently enjoying a five-theatre saturation booking locally. It's a story that demonstrates one more direction in which the movie business is going in pursuit of revitalization.Brother of the Wind is distributed by the Los Angeles-based Sun International Productions, a two-year-old company bringing an old idea up to date. S.I. doesn’t rent its films to theatre owners (the established business model for the industry). Instead, it rents the theatres outright, handles its own promotion and advertising, and takes whatever profit there is over and above expenses.

The method is not new. For years travelling evangelists with “inspirational” films, and pioneer exploiters with “educational” pictures have known how to swing a rental deal. (One Hollywood entrepreneur, Joe Solomon, used to go on the road with both types of picture.) What is new is its use exhibiting general-entertainment features.

S.I. is currently renting houses for two films: Brother of the Wind and Utah-based director Keith Larsen’s Trap on Cougar Mountain. The distributor’s first feature, seen here more than a year ago [1971], was the made-in-Oregon Toklat. Its fourth, set to go before the cameras in January [1973], is tentatively titled Shoshonee.

Arrangements with the actual filmmakers differ. Some movies are completed before they’re bought. Others are co-productions. With Shoshonee, S.I. will be the sole producer, creating the product from start to finish.

Leon Ames will star in the new project, along with a horse and an Indian boy. It was written for Ames by the same John Champion who scripted Brother of the Wind. Scheduled for release in late summer 1973, it will be booked in the new/old rental hall way.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1972. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Brother of the Wind was the second film for which Leon Ames provided the narration for outdoorsman Dick Robinson’s onscreen interactions with Western wildlife. The first was 1971’s Toklat, in which the title role was a grizzly bear at large in rural Oregon. It was also the first feature distributed by Sun International, the distribution company founded by Reyland Jenson. Described as “a devout Mormon [who] felt the family picture side of the 1970s cinema was severely lacking,” Jensen set up his company (later to be known as Sunn Classics) in Utah. His greatest success was director Richard Friedenberg’s 1974 The Life and Times of Grizzly Adams, for which Jensen acted as the executive producer. Shot in Alberta’s Kananaskis country, the feature spun off a two-season television series (1977-1978), two made-for-TV movies (1978 and 1982) and two more theatrical features (1990, 1999), all of them filmed in the U.S.

Shoshonee, the feature that I noted John Champion had written for Leon Ames, was not made by Sun International, nor did it arrive in theatres by the four-wall route. Along the way, the veteran screenwriter made a deal with a major studio — Universal Pictures — to finance and distribute the feature that would be his directorial debut. Retitled Mustang Country, it starred Joel McCrea, who, at 70, was just three years younger than Ames. In his final screen role, he played opposite a horse (a wild stallion named Shoshone) and a young native American (Nika Mina, in his only screen appearance). Set in Montana circa 1925, it was filmed in Alberta’s Banff National Park.

Fun fact: Shortly after the above review was written, I learned that the practice of distributors renting theatres to show their pictures had a name within the industry: four-walling. And it wasn’t just low-rent independent movies that were marketed in this way. Seven months later, in my review of 1973’s Last Tango in Paris, I went on at some length about how United Artists were using the four-walling strategy to maximize their profits from the somewhat notorious Bernardo Bertolucci “art” film.