Tuesday, June 11, 1974.

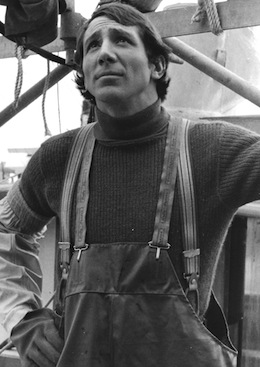

GENTLE-FEATURED AND SOFT-SPOKEN, Johnny Crawford has a thoughtful, almost mournful look about him. He's the sort of person experienced panhandlers seek out in crowds. He looks like a soft touch.

Five years ago, when a friend of Crawford's was taking a film course at the University of Southern California, he asked the young actor to appear in his thesis movie, a 16-millimetre short subject. Reluctantly, Crawford agreed.

"At the time, I thought that maybe it wouldn't be the best thing to let it be known that I was making a student film," Crawford recalled in an interview. "In a way, though, it's turned out to be a real turning point in my career."

The film, called The Resurrection of Bronco Billy, was a lightly comic mood piece focusing on the fantasies of a teen-aged drugstore cowboy. It won its producer, John Longnecker, an Academy Award for making the best short subject of 1970.

It won for Crawford, a former child star, his two most recent feature film offers: starring roles in Donald Driver's adaptation of Desmond Morris's The Naked Ape, and George McCowan's The Inbreaker, as well as the opportunity to make the transition from juvenile to adult performer.

"You know," Crawford says with a touch of wlstfuiness in his voice, "I find that I love to reminisce. I think when I get to he an old guy, I'll be like the old guy in Bronco Billy. His name was Wild Bill Tucker, and he was an old vaudevillian who just loved to tell stories."

At 28, Crawford has more to reminisce about than most. Los Angeles-born, he made his first appearance before the cameras at the age of three.

"It was some kind of wartime movie," he recalls. "I was an extra in a scene with Rosalind Russell, who was handing out chocolate bars to a crowd of kids. I wouldn't give my chocolate bar back, so after that I was blacklisted."

Crawford didn't seriously decide to become an actor until he was six. At that time, he was offered a part in a stage version of Mr. Belvedere. "My parents talked to me about it. I had the impression that it was a big decision.

"What she had heard about kids in films made my mother apprehensive," he said. Neither of Crawford's parents felt any compelling reason to push their children into show business careers because they had come from performing families.

Crawford's maternal grandfather, violinist Alfred Megerlin, was a concertmaster during the 1920s, leading the New York, Minneapolis and Los Angeles orchestras. His maternal grandmother was a violinist.

The music on his father's side, while less serious, was considerably more remunerative. Crawford's paternal grandfather was a Tin Pan Alley song plugger, a pop-music salesman who married a department store piano player. Robert Crawford built his own publishing company — DeSylva, Brown & Henderson and Crawford Music Corp. — into a multimillion-dollar proposition.

"He sold his catalogue to Warner Brothers for $7 million, and went into the stock market. Unfortunately, the elder Crawford made his decision to storm Wall Street in 1929.

Crawford's father, a studio film editor, met his mother, a concert pianist with ambitions of becoming a screen actress, in Los Angeles. When the time came for their son Johnny to make his decision, there was a calm family discussion.

"I was trying to act as If I were giving it a lot of thought," Crawford remembers. "But being in a play seemed very exciting and I really wanted to do it."

Three years later, the Walt Disney studios were developing a TV show called The Mickey Mouse Club, and Crawford was one of the youngsters who turned out to audition for television's best-remembered corps of kid performers, The Mouseketeers.

"My imitation of Johnny Ray won Jimmy Dodd's heart," he recalls. Issued a name shirt and a Mouse-eared beanie, he became a founding member of the Club.

"It lasted six months, he said. "Then they withdrew my option. They started with 24 Mouseketeers, then cut back to 18 and finally to 12."

The Disney training opened the way to other opportunities. Between 1956 and 1958, Crawford was seldom idle. "Those were exciting, dramatic, good days for television," he says. "I had the chance to do a lot of different kinds of role, and work with a lot of top actors on shows like Playhouse 90, Lux Video Theater and Climax! "

In all, he appeared in 59 shows, including 15 productions of NBC-TV's Matinee Theater. "I think I have fonder memories of that than of anything else," he says. "It was an afternoon show, one of the first to be broadcast in colour. It did a different drama every day."

Each show was put together in the space of a week, working in a rehearsal hall until the day of the broadcast, "then we'd finally see the sets." There would be time for one dress rehearsal, and then it would be lunch hour.

"I can remember the quiet just before a production started. There was a regular countdown and then, all of a sudden, the bird would appear (the NBC peacock, once used to introduce colour telecasts), spreading its feathers, and we'd be on. It was really exciting."

In 1958, Crawford was cast in series called The Rifleman. For the next five seasons, in a total of 176 half-hour episodes, he played Mark, the son of rancher Lucas McCain (Chuck Connors).

Crawford's feature film career has been less memorable. In 1956, he starred in The Courage of Black Beauty, a movie pieced together from the pilot episodes made "for a series that didn't make it." The next year, he appeared in The Space Children, "a real three-week job, all about a good Blob."

Johnny Crawford literally grew up on The Rifleman. The show spanned his important growth years between 12 and 16, and when it ended he was ready to make a real teenybopper special, the sort of film that haunts actors as long as they live.

Crawford's "special" was called Village of the Giants (1965), a dance-party adaptation of the H.G. Wells short story Food of the Gods. "I've always been an optimist," he said. "I didn't think it could hurt.

"On the other hand," he says, wincing, "it couldn't possibly help."

Sharing Crawford's embarrassment and his desire to buy up and burn all copies of the film are Ron Howard and Beau Bridges, a pair of young actors who managed to survive the experience.

"Beau and I torture one another just by talking about it," he says with a grin. I hope I never make another one like that."

His next film, the 1966 Western El Dorado, was not at all like it. In its story, Crawford's character is accidentally gunned down by the hero, John Wayne, setting off a blood feud. Among those involved in the villainy was Christopher George, Crawford's co-star in The Inbreaker.

In El Dorado, Wayne also kills off George's character. "He dies very well," Crawford says, admiringly. "He has a real flair for dying."

During the making of El Dorado, Crawford received his draft notice. For the next two years, he worked as a film production specialist involved in the making of training films at the U.S. Army's motion picture centre on Long Island.

Today, Crawford is nearly 30. "I'm looking forward to it," he says. "More so than most, probably. It will be better for my career.

"Being in your 20s is not good at all. It's a transition period (for juvenile actors). It is the time when you have to make a definite change.

"If you haven't done it by the time you're 30, people figure that either you're not serious about show business, or that you were probably pushed into it, or have just decided to drop out.

"I'm looking forward to being past that period of suspense, of not knowing whether I'll be successful or not."

Another possibility is retirement. A combination of careful investment and a trust fund from his child-star years has made Crawford financially independent.

"I've been thinking very carefully about the future," he says. "I live modestly and am frugal about my savings and investments because I'm afraid of losing that independence. If I did that," he adds with a chuckle, "I'd have to go to work."

As it is, Johnny Crawford prefers staying in show business, his family's business for three generations.

The above is a restored version of a Province interview by Michael Walsh originally published in 1974. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: The Inbreaker, the Canadian-made independent film that Crawford was promoting on his visit to Vancouver, was not released in the United States, nor much of anywhere, really. Few people saw his fine performance in that forgotten feature. The Naked Ape, the other picture mentioned during our conversation, was actually damaging to his acting career. Its executive producer was Hugh M. Hefner, founding publisher of Playboy Magazine, and it was made at a time when Hefner was attempting to expand his entertainment empire in new directions. His Playboy Productions division had moved into feature-film financing with two British-based pictures, the Monty Python troupe's And Now for Something Completely Different and director Roman Polanski's Macbeth (both 1971). Promotion for The Naked Ape, based on a book by sociobiologist Desmond Morris, included a full-frontal nude appearance by Crawford in the magazine, earning him the distinction of being the first male to bare all in its pages. The picture was released in the U.S. and, perhaps, helped focus his thinking about his future.

Little-seen on screen thereafter, Crawford remained friends with Chuck Connors until his former co-star’s death in 1992. A year earlier, they worked together one last time, reprising their Rifleman roles in a Kenny Rogers made-for-TV movie called The Gambler Returns: The Luck of the Draw. Around that time, the child star who'd grown up in a musical family returned to his roots. Drawing inspiration from the collection of sheet music and original recordings inherited from his paternal grandfather, he formed the Johnny Crawford Dance Orchestra, a big band that performs the music of the 1920s and 1930s. In March, 2015, he was among the guests honoured at Virginia's Williamsburg Film Festival, and is currently scheduled to appear at the Fourth of July Celebration of Freedom concert in Pearland, Texas.