Saturday, May 1, 1976

ACCORDING TO FORMER PRIME minister John Diefenbaker, one of his proudest accomplishments was the passage, in 1960, of a Canadian Bill of Rights. "Malarkey,” says author Walter Stewart.

''You can take Diefenbaker's Bill of Rights, and the panel off the back of a box of corn flakes, and send away for a Frisbee," Stewart said in an interview. "It's not worth the parchment it's printed on."

"We used to have a bunch of Coast Guard ships that were no damn good in a storm. That's Diefenbaker's Bill of Rights." If his new book — But Not in Canada! Smug Canadian Myths Shattered by Harsh Reality — is shaped to any purpose, Stewart says, it is to awaken Canadians to the fact that this country needs a "real" bill of rights.

"Most Canadians dwell in the delusion that they have all the rights they need." Well, that's just not true, says Stewart. Until we have a bill of rights embedded in a constitution, he says, our rights will continue to be swept away at the moments when they are most needed.

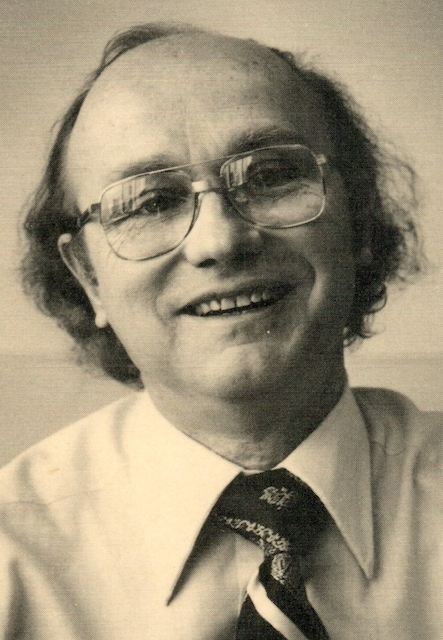

Stewart, 45, is a crusader, He is also a top investigative reporter, “a rare and precious commodity in this country," where "working journalists have a problem that the Americans don't have: the breadth and depth of our libel laws."

His complaint: "It's a tradition in Canada not to open doors, but to close them. The same people who hide things under the bed have the keys to the bedroom."

Canadian law offers virtually no protection to truth-seekers, with the result that “our journalists are always on the defensive.''

The son of a salesman who left the business world to become a writer, broadcaster and social activist, Stewart grew up in a politically-aware environment. His mother was, at one time, Ontario secretary of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) political party. [In 1961, the CCF became the New Democratic Party, or NDP.]

He's always held strong, often controversial opinions. In 1953, the year he would have graduated from Toronto's Victoria College, he decided that "the university, as a system, was a crock."

He dropped out, telling all in a bylined story in The Varsity, the University of Toronto's campus daily. His story was seen in the offices of the Toronto Telegram, and Stewart was offered a job as a reporter.

For the next nine years, the time it took "to get to be a real reporter," he worked for the daily newspaper fondly known as The Tely. He left in 1962 to join The Star Weekly, switching to the newsmagazine Maclean's in 1968, when the SW folded. Currently, he is Maclean's Washington bureau chief.

"I've always liked what I was doing," he says, "and have done it fairly well. I feel strongly about things and tend to argue them rather than merely describe them. I'd say that makes me a modern journalist."

With three previous books to his credit — Shrug, an argumentative assessment of [Prime Minister] Pierre Trudeau, Divide and Con, and Hard to Swallow: Why Food Prices Keep Rising and What Can Be Done About Them — he is hard at work on two more.

One will be "a book of quotations — Americans looking at Canada." The other, more serious work will attempt a fairly tough-minded comparison of American and Canadian political traditions.

The above is a restored version of a Province interview by Michael Walsh originally published in 1976. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: It was an exciting time to be a journalist. Three weeks before sitting down with Walter Stewart to talk about his book, I’d reviewed All the President’s Men. Director Alan J. Pakula’s adaptation of the book by Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein had made popular culture heroes out of the investigative journalists who’d pursued the Watergate scandal that resulted in the 1974 resignation of American President Richard Nixon. Following the film’s release, I recall an article in The Columbia Journalism Review noting an enrolment surge in U.S. journalism schools. It made the point that there were at that moment more students in j-schools than there were media jobs for them to step into. Significantly, the newsroom photo that accompanied the piece featured actors Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman, rather than the real-life reporters Woodward and Bernstein.

As I already had a job, I wasn’t worried. Because Woodward and Bernstein were my contemporaries, they were not my heroes. In Canada, we had our own investigative icons. For years, I'd taken my inspiration from such journalistic giants as Toronto Star columnists Pierre Berton and Ron Haggart. And, of course, Walter Stewart. What I did not know, until our interview, is that we shared an oddly similar entry into the business of newspapering. In my case, a piece that I’d written for The Varsity in late 1966 was noticed by an editor at the Toronto Star. Two months later, I dropped out of college and, like Stewart, went to work for the Toronto Telegram. It was comforting, in 1976, to be in that moment of professional glory, and within an honourable tradition of insouciant hope.

See also: My review of Walter Stewart's 1976 book But Not in Canada! Smug Canadian Myths Shattered by Harsh Reality.