Saturday, July 28, 1973.

LA VRAIE NATURE DE BERNADETTE. (The True Nature of Bernadette). Music by Pierre F. Brault. Written and directed by Gilles Carle. Running time: 115 minutes. Mature entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: Very frank treatment of sex. In French with English subtitles.

INTERNATIONALLY, GILLES CARLE IS one of Canada's best-known filmmakers. The Québec-born Carle’s recent movies have been among this country's official entries in the Cannes Film Festival for the last two years.

Locally his Les Mâles, the only Canadian film on last year's [1972] Varsity Festival program, proved to be a solid hit. This year [1973], there are two domestic features on the Varsity schedule — La Mort d'un Bûcheron and La Vraie Nature de Bernadette — and both are Gilles Carle films.

His recent work reminds us that comedians seem to be natural-born preachers. Charlie Chaplin, once known as "the funniest man in the world," was always good for a sermon on the subject of socialism. Bob Hope can still wax pontifical on patriotism and even Bill Cosby gets serious on the drug question.

It’s little wonder, then, that Carle, Canada's most gifted director of screen comedy, wants to preach social revolution. At the same time, though, he still wants to make people laugh. His two new pictures are most successful when the director’s separate purposes are least mixed.

Bernadette, made last year, is the steadier of the two. It shared in the top honours at the most recent Canadian Film Awards with Bill Fruet’s Wedding in White, and collected a best actress award for its star, Micheline Lanctôt.

(An interesting subject for further study is the Québec talent bank, the source of Canada's most distinctive and stylish performing artists. Unlike their English-speaking confrères, Québec filmmakers seem to have no trouble finding dynamic and attractive Canadian actors to star in their movies).

In his earlier comedy, Les Mâles (1970), Carle told the story of two men who dropped out of the mainstream to seek fulfillment in the quietude of nature. Now, in Bernadette, he offers a slightly more serious variation on the same theme.

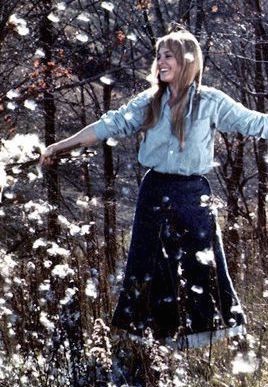

This time his dropout is a woman. The 30-something wife of a Montreal lawyer, Bernadette Brown (Lanctôt) has planned her “disappearance” very carefully.

Unbeknownst to her husband, she has bought a ramshackle farm in rural Québec. One morning she gathers up her little boy (Yannick Therrien) and leaves.

It's one thing when men drop out. As Carle showed in Les Mâles, men who opt for a wilderness life are part of historic tradition. At best they are considered delightfully eccentric; at worst, a nuisance.

In general, though, they are tolerated.

It’s quite another thing for a woman. Bernadette certainly has logic on her side. An intelligent, level-headed woman, she has seen through the urban madness and decided that she wants to bring up her child to be one with nature and to appreciate his own life force.

Her new neighbours, a community of poverty-line farmers and small-town workers, are dumbfounded. Not having had the opportunity to sample the affluence that Bernadette rejects, they are considerably less sure about the natural superiority of their way of life.

To them, she's a nut.

More alarmingly, her well-reasoned open-mindedness embraces the concept of free love. As far as the locals are concerned, that makes her a whore.

Their impressions are reinforced when her little farm becomes the local drop-in centre. Among the drop-ins are a trio of pleasantly dirty old men who avail themselves of therapeutic massages in Bernadette's parlour, a crippled farm hand and a pair of leather-jacketed transients.

Most pathetic among them is a small boy. Mute and unable to walk, he has been left in Bernadette’s care by his unwed mother, one of the village girls who is running away to the city.

There is a fine line between love and hate. Following her instincts, Bernadette manages to find water where there was supposed to be none.

When a van full of her goods arrives from Montreal, she gives them away. With a mother's patience she even manages to start the mute child walking and talking.

Rushing from one extreme to the other, the locals hail her as a saint. A Montreal newspaper picks up the story and suddenly her yard is crowded with miracle-hungry pilgrims.

Watching all of this with some disgust is her neighbour Thomas (Donald Pilon). A hardworking young farmer, he has been trying to rouse his fellow farmers to protest government price-board policies.

He’s smart enough to know that Bernadette is no whore, and cynical enough not to believe her a saint.

Like the eccentrics in Les Mâles, she is merely a romantic, one who's unable to see either consequences or contradictions in her actions. Impulsively she follows her different drummer, unaware of the havoc spreading in her wake.

For the most part, Carle views Bernadette’s plight lightly. Surrounded by a collection of well-cast crazies, Lanctôt has merely to maintain an amiable, committed calm to provide the film with a fine, firm centre.

It works very well for the first three-quarters of the film. It is not till then that Carle begins heavily underlining a more serious mood and building towards a tragic climax.

Without in any way disparaging some of the fine films seen in this year’s [1973] Varsity program package, I think it is fair to say that Carle’s were the most important movies shown. Also, isn’t it ironic that when his outstanding domestic films cross this country, they must be seen in the context of an “international” movie package?

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1973. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: In 1973, when La Vraie Nature of Bernadette arrived in Vancouver, I was still willing to believe that the Canadian Film Development Corporation, the federal agency created to “foster and promote” a domestic feature film industry, was sincere in its mission. My comment on “the irony” of viewing Canadian movies in the context of an international film festival was meant as constructive criticism. Carle’s fifth theatrical feature, Bernadette had been a big winner at the 24th annual Canadian Film Awards. It took home five Etrog statuettes, including the prize for best actress (Micheline Lanctôt) and supporting actor (Daniel Pilon), best director and screenplay (both to Carle) and music (Pierre F. Brault). (Later, in 1984, it was named one of the Top 10 Canadian Films of All Time in a Toronto International Film Festival poll.)

Over the years, I lost any faith at all in the CFDC’s sincerity. Morphing into an entity called Telefilm Canada in 1984, it has been in existence for nearly 50 years, during which time it has lurched from one failure to another. Although it allowed some space for the development of a Canadian cinema, its deliberate inattention to such issues as distribution and exhibition made the establishment of anything resembling a domestic feature film industry an illusory dream. Québec’s artists were skeptical from the beginning, with the best of them recognizing their own société distincte and embracing the sovereigntist cause. English Canadians bought into Ottawa’s con game for a time, though the best of them hoped that Hollywood would one day call. The result has been a legacy of dashed hopes and one-off feature projects, among them an occasional cinematic gem such as La Vraie Nature de Bernadette.