Tuesday, July 15, 1966.

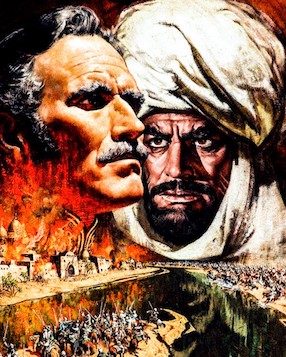

KHARTOUM. Written by Robert Ardrey. Music by Frank Cordell. Directed by Basil Dearden. Running time: 128 minutes. General entertainment.

CINERAMA, BIGGEST OF THE big screen processes, has long suffered from an embarrassing inability to tell a story. Man does not live by roller coaster rides alone, however, and recent productions, such as The Greatest Story Ever Told, The Hallelujah Trail and The Battle of the Bulge [all 1965] have attempted to serve up as much scenario as scenery.

With Khartoum, the process comes of age, finding its medium in the adventure epic. And what better star to bring the word forth from the mountain than that hero to all nations, Charlton Heston?

The Great Grimace is cast as British General Charles “Chinese" Gordon, a man to whom God, Queen and Country were the all-important values, and to whom Her Majesty's government looked when its African empire was endangered by a nationalist uprising.

Opposite Heston, and in opposition to Gordon, stands Laurence Olivier as Muhammad Ahmed, “the Mahdi,” a self-styled chosen one of Islam. His visions of the Prophet have commanded him to worship in the Mosque of Khartoum. But to do so, he must first put all unbelievers to the sword.

The time is 1883 to 1885. The place is Sudan, “where the Nile divides.” The battles, performed by the expected cast of thousands, are epic.

By now, both Heston and Olivier have established themselves as formula actors. Gordon, in analysis, stands as six parts El Cid to four parts Moses. The Mahdi, portrayed in Olivierian blackface, combines seven parts Othello, two Henry V and one Hamlet.

The end result is an entertainment soda, enriched with a highly palatable base and made more attractive by the froth of Cinerama spectacle.

The above is a restored version of a Varsity review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1966. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Canadians, it must be said, live to serve Empire. Within days of Britain’s August 4, 1914 declaration of war, Sir Wilfrid Laurier rose in the House of Commons to declare: “When the call comes our answer goes at once, and it goes in the classical language of the British answer to the call of duty: ‘Ready, aye, ready.’” So it should come as no surprise that Canadians were involved in the story told in Khartoum. It began when Crimean War veteran Garnet Wolseley (played in the film by Nigel Green) was tasked with leading a force to relieve what turned out to be a ten-month-long siege.

Lord Wolseley’s resumé included service in the Dominion of Canada, where he had led the 1870 Red River Expedition to assert the newly-formed nation’s sovereignty over Manitoba and the North-West Territories. He’d been impressed by the skills of the country's boatmen and, as a result, his Nile Expedition became the first overseas deployment of Canadians in a British imperial conflict. The contingent of 377 voyageurs arrived at the Egyptian port of Alexandria on October 7, 1884. By the end of the month, they had begun transporting the 5,400-man relief force up the river into Sudan. As the movie makes clear, they were too late. Khartoum fell to the Mahdists on January 26 —General Gordon and his entire garrison were slaughtered — just two days before an advance element of the British army came within sight of the city. Sixteen Canadians died during the journey.

Here’s a depressing fact. All of Canada’s war dead have died in foreign conflicts, wars fought in the service of an Empire — the British until 1945, the American thereafter — or “peacekeeping” missions determined by international bodies such as the United Nations. For a brief time after the U.S.-led Korean "police action," Canadians dabbled with the idea of real sovereignty, but eventually returned to our default position, repeating “ready, aye, ready” to the imperial power of the day. Currently, our prime minister is perched like a parrot on the shoulder of the American president, repeating bellicose nonsense about our “support” for Ukraine in its ginned-up confrontation with Russia. If history — or the movies — are any indication, that’s sure to go well.

See also: Among the defeats suffered by the British was the 1879 Battle of Isandlwana, the subject of director Douglas Hickox’s 1979 feature Zulu Dawn.