Saturday, February 4, 1976.

"THE PARTI QUÉBÉCOIS CAME to power as a backlash to the October Crisis," director Michel Brault said Thursday night [February 2, 1976]. In proclaiming the War Measures Act, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau "made a mistake he shouldn't have made."

Brault, 49, was in B.C. to open a Canada Council-sponsored series of Visiting Québécois Film-Makers at Simon Fraser University. He made his remarks in the discussion period that followed a showing of his prize-winning feature, Les Ordres.

His film, voted best picture of 1975 by the Canadian Film Awards jury in October, attracted some 450 persons to the SFU Images Theatre. A powerful and compassionate drama, it uses the documentary technique to tell the story of five people arrested and held without charge as a result of the "special law."

Though its characters are fictional, their experiences are based on fact. To develop his script, Brault interviewed 50 actual detainees.

"One of the reasons I made the film is that after the October Crisis Mr. Trudeau said 'let's forget about it.' Now, I think, maybe he has more to hide than to forget."

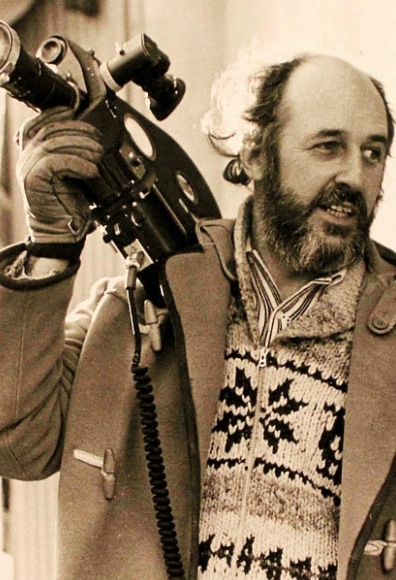

In a question-and-answer session that lasted more than two hours, the patriarchally-bearded Brault expressed disappointment at the film's commercial failure in English-speaking Canada. "I didn't make it for the people who already know. I wanted to bring it to the ordinary people in the theatres," he said.

"I wish that Canadians could be much more aware of what happened,'' he told his polite but politically divided audience. "Many people never really realized that (these incarcerations) happened," he said.

"One of the reasons the populace is so badly informed is because it is so easy in government to do what you want in secret," he said. "We have the tendency to elect some people as head of the country then forget about them."

Canadians need to participate in their democracy more, Brault said. "There should be nothing behind closed doors. The aim is to have everything limpid and clear . . . We should have more control over our MPs, the ministers and the prime ministers."

A moviemaker for more than 20 years, Michel Brault has achieved near-legendary status within the Canadian film community. He has been associated, in one way or another, with some of the most distinguished and controversial features to come out of the National Film Board, among them 1971's L'Acadie, L'Acadie and Mon Oncle Antoine, as well as Kamouraska (1973).

A member of the Parti Québécois, he spoke out in favour of civil liberties, prison reform, openness in government and Québéc independence. In a brief interview following the discussion period, Brault told me that he has been a separatist since 1962, the year that an NFB colleague urged him to read Marcel Chaput's then-controversial book on the subject (1961's Why I Am a Separatist).

"The question of the independence of Québéc is a very simple one," he said. "It is just being dramatized by people who have an (economic) interest in Québéc not separating."

According to BrauIt, "the Sun Life move is proof that (corporate interests) don't like the way the people of Québéc want to run their own affairs. Well, we're just starting to sweep the floor, and it's a large floor."

Serene and confident in his belief that independence will come, Brault doubted that there could ever be another War Measures Act crisis. "The people cannot be fooled like that again," he said.

Creatively, Brault continues to confine his considerable talents to Québéc productions. Currently, he is working on two projects. One, a series of programs on French folk music in North America, is being prepared for Radio-Canada's television network. The other, a series of films on Québéc's craftsmen, will be produced by the NFB.

The above is a restored version of a Province interview by Michael Walsh originally published in 1976. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Just as the National Film Board of Canada once said that it made movies "to interpret Canada to Canadians," Michel Brault made it his cinematic mission to do the same for Québéc. Born in 1928 in Montréal, the teenaged Brault pursued his passion for photography, switching to cinematography after meeting student filmmaker Claude Jutra. (Their 1949 experimental short Mouvement perpétual won the 1950 Canadian Film Award for best amateur film.) Hired by the NFB as an assistant cameraman in 1950, he quit three months later, discouraged by the Ottawa-based agency's anglophone working environment. He returned to the Board with considerably more experience and personal clout when it relocated its headquarters to Montréal in 1956. Together with such Québécois cinéastes as Jutra, Pierre Perrault, Marcel Carrier, Claude Fournier and Gilles Groulx, he was part of a generation of film artists at the heart of French Canada's "Quiet Revolution," the political and social movement that shaped modern Québéc. His 1976 visit to Vancouver came at a time when Western Canadian filmmakers recognized the achievements of their Québéc colleagues, and hoped to build upon them. Although Brault, who died in September 2013 at the age of 85, would not see an independent Québéc, he did influence independent Québéc filmaking into the 21st century. His documentary short, A Freedom to Move, the first film shot in the giant screen Omnimax process, was made for Vancouver's Expo 86. His final feature, 1999's Quand vous serez parti . . . vous vivrez encore, was a return to political cinema, an historical drama that told the story of the 1837 Rebellion in Lower Canada (and can be viewed as a companion piece to director Laurence Keene's 1985 feature Samuel Lount, about the parallel Rebellion in Upper Canada). Britain's Guardian newspaper marked his passing with a detailed obituary in which he's identified as "one of the great unsung heroes of cinema."