Monday, October 26, 1981.

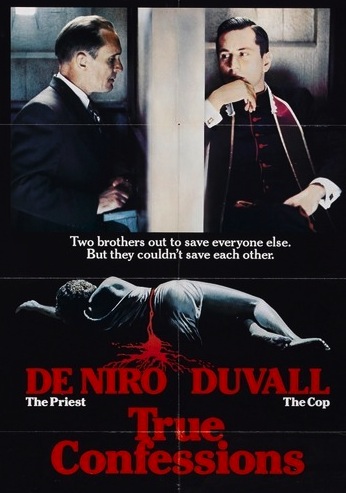

TRUE CONFESSIONS. Written by Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, based on Dunne's 1977 novel. Music by Georges Delerue. Directed by Ulu Grosbard. Running time: 108 minutes. Restricted entertainment with the B.C. Classifier's warning: some nudity and suggestive scenes; scene of autopsy.

YOU DON'T HAVE TO BE Catholic to appreciate True Confessions. An intense, superbly crafted suspense drama, it can be enjoyed as an Irish American variation on The Godfather.

The similarities are obvious. Like The Godfather, True Confessions opens with a wealthy Catholic wedding. The time is 1948 and Jack Amsterdam (Charles Durning), a Los Angeles construction company owner with underworld connections, is marrying off his daughter.

Like The Godfather movies, True Confessions is a must-see film for its acting alone. Robert Duvall, a 1972 Oscar nominee for his portrayal of Corleone family lawyer Tom Hagen, and Robert De Niro, a winner in 1974 for his performance as the young Vito Corleone, here play the Spellacy brothers.

De Niro is the Right Reverend Monsignor Desmond Spellacy, a dynamic young priest whose administrative abilities are the reason for his rapid rise in the Church hierarchy. His superior, Los Angeles Cardinal Danaher (Cyril Cusack), is recommending his promotion to bishop.

Duvall plays Tom Spellacy, the Monsignor's older, rougher brother. A police homicide detective, Tom is an angry, embittered Irish cop.

You don't have to be Catholic to feel for Tom. He's been trying to stay honest. Then, on the morning of the Amsterdam nuptials, he is called out to deal with a death in a downtown brothel.

While Father Des is celebrating with the Amsterdam family, Tom is identifying the body of an aging parish priest, a clergyman whose heart failed him during his moment of passion with a prostitute. As it turns out, the house madam, Brenda Samuels (Rose Gregorio), is an old friend and a recent women's prison inmate.

Brenda reminds Tom of some of his own past sins. He was involved when she was part of Amsterdam's prostitution operations. He would have gone to jail with her, she says, but was protected because Amsterdam didn't want to embarrass Tom's brother, the Monsignor.

While Tom is chewing on that, we learn that Desmond is the Cardinal's expeditor, a priest who "looks like a leprechaun (but) thinks like an Arab." Amsterdam's companies do much of the building for the diocese, and the Monsignor is the deal-maker.

You don't have to Catholic to follow the complex pattern of interrelationships woven through this John Gregory Dunne-Joan Didion screenplay. When the nude, mutilated body of would-be actress and sometime prostitute Lois Fazenda (Amanda Cleveland) is found in a vacant lot, it's obvious why the cop wants to get the killer. It's his job and the murderer has to be a nut.

It may be, though, that only a Catholic can fully share in director Ulu (Straight Time) Grosbard's richly realized tale of guilt and absolution. Indeed, Guilt exists as a living force in the lives of the Spellacy brothers.

A hulking, brutal spectre, Guilt accompanies the cop wherever he goes. Tom, a failure as a husband and father, feels ineffectual. He sees raw evil all around him. He is sickened by the knowledge that he has been and continues to be part of it.

Guilt is a more subtle presence for Desmond. He has had nothing but success, approval and respect. Even so, his soul is troubled.

When the Cardinal pensions off his old mentor, Monsignor Seamus Fargo (Burgess Meredith), dismissing him as "a pain in the neck," Desmond begins to seriously doubt his own priestly vocation. When Tom insults the sinister Amsterdam to his face, Des is overcome by the feeling that "looking the other way" has become "a full time job."

Their guilt focuses and becomes embodied in the Amsterdam character. He is an affront, an evil man whose evil deeds have brought him prosperity and honour because too many good men have looked the other way.

True Confessions is the stark, powerful and very Catholic story of the Spellacy brothers, their sins, repentance and harsh, self-imposed penance. It is, at its heart, the story of their quest for absolution.

Like Roman Polanski's Chinatown, True Confessions is a deeply moral drama. It hides its turbulent tale of spiritual corruption beneath a languid, apparently unhurried surface.

The above is a restored version of a Province review by Michael Walsh originally published in 1981. For additional information on this archived material, please visit my FAQ.

Afterword: Ulu Grosbard was already 33 years old in 1962, the year he made his debut as a New York stage director. Born in Belgium, he brought a wealth of life experience to his work, including flight from the Nazi occupation, five years working as a diamond cutter in Havana, Cuba, and a 1950s hitch in the U.S. Army. Assessing his achievements, Guardian obituary writer Ronald Bergan tells us that he helped launch the careers of Dustin Hoffman, Robert Duvall and John Voight, all of whom were involved in director Grosbard's 1965 Off-Broadway revival of Arthur Miller's A View from the Bridge. Hoffman later starred in two of Grosbard's seven feature films — the decidedly odd 1971 comedy Who Is Harry Kellerman and Why Is He Saying Those Terrible Things About Me? and the drama Straight Time (1978). Robert De Niro, who co-starred with Robert Duvall in True Confessions, worked with Grosbard again in his 1984 drama Falling in Love. Though Jewish, in his work Grosbard demonstrated a remarkable empathy for Catholicism. His made his Broadway debut in 1964 directing The Subject Was Roses. The story of an Irish American family, it won both a Pulitzer Prize and a Tony for playwright Frank D. Gilroy, and a Tony nomination for its director. Four years later, Grosbard directed original stage cast members Jack Albertson and Martin Sheen in the screen adaptation, his own feature film debut. True Confessions was similarly pitch perfect in its appreciation of the nuances of American church practice, making that period drama a classic of its type. Ulu Grosbard died in 2012 at the age of 83.